Doing Business With & In Canada

Table of Contents

Non-residents of Canada are subject to Canadian income tax if they carry on business in Canada or are employed in Canada in a particular taxation year. Non-residents with business connections to Canada may also have other consequential Canadian income or sales tax obligations. Moreover, when a non-resident sends its employees to Canada, it not only creates a risk of creating a taxable nexus in Canada for the non-resident itself: this may also cause the visiting employee to become subject to Canadian income tax by virtue of being “employed in Canada,” and create a corresponding Canadian employer withholding and remittance obligation on the non-resident employer in respect of salary and other remuneration paid to the employee in respect of employment services rendered in Canada. It is very important for non-residents to be aware of what activities will cause them to have Canadian tax obligations, and what the alternatives are for dealing with them.

Table 1. Non-Residents Carrying On Business in Canada

| Issue | Non-residents located in country with a Canadian tax treaty | Non-residents located in country with no Canadian tax treaty |

|---|---|---|

| Income tax return required if carrying on business in Canada | Corporations* | Corporations* |

| Canadian taxation of income from carrying on business in Canada | No, if non-resident is both (1) eligible for benefits under its home country’s tax treaty with Canada, and (2) not carrying on business through a “permanent establishment” in Canada** | Yes |

| Employees present in Canada: Canadian tax on employee remuneration | Yes, unless relief provided to non-resident employee under tax treaty between Canada and non-resident employee’s home country | Same as residents of tax treaty countries |

| Employees present in Canada: Non-resident employer obliged to withhold and remit Canadian tax on employee remuneration | Yes, unless (1) non-resident employee is treaty-exempt (see above) and (2) employer obtains exemption under Regulation 102 waiver or qualifying non-resident employer certification program*** | Yes, unless (1) non-resident employee is treaty-exempt (see above) and (2) employer obtains Regulation 102 waiver |

** A permanent establishment is as defined in the relevant tax treaty, typically as either a fixed place of business or an employee who exercises authority to conclude contracts in the non-resident’s name (the Canada-U.S. tax treaty also has a “services PE” provision).

*** This requires that the treaty-exempt non-resident employee either works in Canada for less than 45 days in the calendar year that includes the time of the payment, or is present in Canada for less than 90 days in any 12-month period that includes the time of the payment.

1. Carrying on Business in Canada

- A non-resident that is “carrying on business in Canada” for income tax purposes in a taxation year will be (1) subject to Canadian income tax, unless the non-resident has no Canadian “permanent establishment” and is resident in a country that has (and eligible to claim relief under) a tax treaty with Canada and, and (2) required to file a Canadian income tax return for the year.

- a non-resident may be considered to be “carrying on business in Canada” either under principles developed in the case law or under rules in the ITA that deem certain activities to be carrying on business in Canada

- A non-resident can also be found to be carrying on business in Canada through the activities of an agent in some circumstances.

- The presence of a non-resident’s employees in Canada may also result in the employee having a Canadian tax liability and the non-resident employer having a related withholding and remittance obligation on the employee’s remuneration.

- To prevent a non-resident with Canadian activities from having Canadian tax obligations, in some cases it makes sense to use a Canadian subsidiary to perform in-Canada activities and/or “second” (loan) a non-resident’s employees to that Canadian subsidiary to the extent they need to be in Canada.

Non-residents with business connections to Canada must consider whether their activities constitute “carrying on business in Canada.” This could occur in a number of ways:

- direct dealings with Canadian customers or suppliers;

- sending employees to Canada or having agents in Canada acting in the non-Canadian’s name; or

- for non-Canadian members of a multinational enterprise (MNE), providing goods or services to Canadian members of the MNE.

The concept of “carrying on business in Canada” is relevant to a non-resident’s Canadian income tax obligations in two ways (a similar concept applies to sales tax as well). First, a non-resident corporation carrying on business in Canada during a particular year must file a Canadian income tax return for the year, whether or not tax is owing. Moreover, a non-resident of Canada carrying on business in Canada is subject to Canadian income tax on any related income, unless a tax treaty provides relief from Canadian taxation and that non-resident meets the conditions for claiming that relief (typically this means not having a “permanent establishment” in Canada). As Canada has tax treaties with almost 100 countries, it is quite common for a non-resident corporation to be required to file a Canadian tax return (i.e., because of carrying on business in Canada) without meeting the test for actually being taxable in Canada on business income (i.e., having a “permanent establishment” in Canada”).

A. General Principles

If the non-resident concludes revenue-generating contracts in Canada (i.e., a binding offer is accepted by someone within Canada), the cases have often considered this to be “carrying on business in Canada.” Canadian tax counsel typically therefore encourage non-residents to (1) not execute any business contracts while physically present in Canada, and (2) make sure their contracts with Canadian customers are structured such that the non-resident formally agrees to the contract after the customer has already done so (i.e., in technical legal terms, the Canadian customer makes the “offer”, and the non-resident “accepts” it from outside Canada).

A “carrying on business in Canada” determination is very fact-specific, in terms of the frequency, extent and nature of the activities occurring in Canada. Various indicia of carrying on business in Canada are found in the caselaw:

- as noted above, whether the non-resident’s business contracts are completed in Canada;

- the presence or absence in Canada of the non-resident’s employees or agents;

- whether the non-resident has any office or other place of business in Canada;

- whether the non-resident has registered under commercial law to do business in Canada;

- whether the non-resident solicits business transactions from within Canada;

- whether the non-resident’s bank account used for Canadian transactions is located in Canada, and the place where payment is made;

- the place where goods are delivered (and legal ownership transfers) or services are provided, and where the profit-making activities occur;

- whether the non-resident’s name and business are listed in a Canadian directory; and

- whether any activities occurring in Canada are merely ancillary to the main business.1 For examples of the CRA applying these criteria in its administrative positions, see CRA documents 2012-0438691E5, dated 17 October 2012; 2006-019443, dated November 20, 2006; 2001-0116133, dated July 24, 2002; and 2000-054455, dated October 23, 2001.

1.53 While a determination of the place where a particular business (or a part of the business) is carried on (that is, the location of the source of the business income — see the comments starting at ¶1.48) necessarily depends upon all the relevant facts, such place is generally the place where the operations in substance, or profit generating activities, take place. For the following particular types of business, the following factors (among others) should be given consideration:

- development and sale of real or immovable property – the place where the property is situated;

- merchandise trading – the place where the sales are habitually completed, but other factors, such as the location of the stock, the place of payment or the place of manufacture, are considered relevant in particular situations;

- transportation or shipping – the place of completion of the contract for carriage, and the places of shipment, transit and receipt;

- trading in intangible property, or for civil law incorporeal property (for example, stocks and bonds) – the place where the purchase or sale decisions are normally made;

- money lending – the place where the loan arrangement is in substance completed;

- personal or movable property rentals – the place where the property available for rental is normally located;

- real or immovable property rentals – the place where the property is situated; and

- service – the place where the services are performed.

1.54 Other factors which are also relevant, but generally given less weight than the factors listed above include, but are not limited to:

- the place where the contract for the sale of property or the provision of services is formed or entered into

- the place where payment is received

- the place where assets of the business are located; and

- the intent of the taxpayer to do business in the particular jurisdiction.

A non-resident seeking to minimize the risk of carrying on business in Canada should reduce the scope of its “in Canada” presence to the greatest degree possible. This means ensuring that business contracts are not concluded in Canada and undertaking outside of Canada as much of the revenue-generating operations of the business as possible.

B. Deeming Rules

- producing, growing, mining, creating, manufacturing, fabricating, improving, packing, preserving or constructing, in whole or in part, anything in Canada;

- soliciting orders or offering anything for sale in Canada through an agent or servant, whether the contract or transaction is to be completed inside or outside Canada or partly in and partly outside Canada; or

- disposing of a Canadian resource property, timber resource property or interest in Canadian land other than as part of a capital transaction (i.e., where the non-resident is speculating or in the business of buying and selling such property).

“Soliciting orders or offering anything for sale” is the element of the deeming rules most frequently encountered by non-residents. General awareness advertising or marketing in Canada clearly does not rise to this level. Soliciting or even completing sales with Canadians from outside of Canada via the Internet based on a server located outside of Canada would also not constitute “soliciting orders . . . in Canada.” However, making a binding “offer” (whether or not accepted) from within Canada would be deemed to constitute carrying on business in Canada.3 Note: it is the activity (soliciting orders or making offers), not the person at whom the activity is directed or the subject matter of the transaction, that must be “in Canada” for the deeming rule to apply: see Maya Forestales S.A. v. The Queen, 2005 TCC 66 at para. 34. An “offer” in this sense has been held to have its contract law meaning of something that, if accepted, constitutes a binding legal obligation. Conversely, the courts have stated that “In considering whether the Plaintiff was ‘soliciting orders’ in Canada, I do not agree that the words can be extended to include ‘a mere invitation to treat.’”4 Sudden Valley Inc. v. M.N.R., 75 DTC 263 (TRB); aff’d 76 DTC 6448 (FCA). Hence, to avoid the application of the deeming rule, a non-resident’s “in Canada” activities must be very careful not to go beyond inviting customers to themselves make an “offer” to avoid being deemed to be carrying on business in Canada.

A special rule (s. 115.2) provides relief to foreign investment funds, which are deemed not to be “carrying on business in Canada” solely by reason of using Canadian service providers to deliver “designated investment services.” Essentially, a non-resident investment fund that uses a Canadian resident to provide certain investment management advice, buy and sell securities that are “qualified investments,” or perform custodial and other administrative services relating thereto will not thereby be deemed to be “carrying on business in Canada” if it otherwise meets the various requirements of this safe harbour provision.

C. Agents

While the most common form of carrying on business in Canada is the presence of the non-resident’s own employees in Canada, the activities of others “in Canada” may also be attributed to a non-resident. Specifically, an agent (i.e., someone who interacts with third parties on behalf of and in the name of, and who follows the instructions of, another person) who has the power to bind the non-resident as regards sales contracts will be considered to be acting on behalf of the non-resident, and that person’s activities may cause the non-resident to be considered to be carrying on business in Canada. A non-resident can therefore be carrying on business in Canada 5 See for example Pullman v. The Queen, 83 DTC 5080 (FCTD). With respect to investment management services provided in Canada to non-residents, see the discussion above of the deeming rule in s. 115.2 providing a safe harbour for qualifying activities. without any of its own employees ever entering into Canada.

A non-resident that engages persons other than employees to perform business functions in Canada should ensure that the third party’s status is not that of an “agent”. Instead, the third party’s role should be structured as an independent contractor that is providing specific agreed-upon services to the non-resident in the course of the contractor’s own business, not an extension of the non-resident’s business.

Other relevant issues for non-residents with a material Canadian presence include the following:

- Permanent Establishment: for non-residents who are carrying on business in Canada and are fiscally resident in a country with a Canadian tax treaty, whether the non-resident has a “permanent establishment” in Canada, either by virtue of having a fixed place of business in Canada 6 CRA auditors will frequently assert the presence of a Canadian permanent establishment if office space of a Canadian group member is formally set aside and made available to visiting employees of a non-resident group member. This issue must be carefully managed. or employees/agents in Canada who exercise authority to conclude contracts on behalf of the non-resident (see below under 2. Permanent Establishment in Canada); and 7 The Canada-U.S. tax treaty has an additional “services PE” article that may deem a U.S. resident to have a Canadian permanent establishment if the U.S. resident’s employees perform services in Canada in excess of 183 days during any 12-month period.

- Employee Taxation/Employer Remittance: for non-residents who send employees to Canada from time to time, whether (1) those employees are themselves subject to Canadian income tax on a portion of their earnings by virtue of performing employment services in Canada, and (2) their employer has a corresponding Canadian withholding and remittance obligation (see below under 3. Sending Employees to Canada).

Where the nature of the business is such that certain activities must be performed in Canada and they could suffice to constitute carrying on business in Canada, non-residents will often use a new or existing Canadian subsidiary (Canco) to perform the “in Canada” activities. For example, the non-resident may have the Canco enter into a separate agreement with Canadian customers to perform certain activities directly for them, or may enter into a services agreement with the Canco for the Canco to perform “in Canada” activities for the non-resident (not as the non-resident’s agent but rather as an independent service provider). The goal in either case is to localize the “in Canada” activities to the Canco, so as to eliminate any Canadian tax obligations for the non-resident.

If employees of the non-resident are required to be in Canada for material periods of time, it may also be advantageous to formally “second” those persons to the Canadian subsidiary (i.e., while these persons are in Canada their employer is the Canco, not the non-resident), in conjunction with a services agreement between the non-resident and the Canco. In this scenario the Canco assumes the related employment supervision and tax obligations. There are a variety of ways in which a non-resident can structure its business dealings with Canada, each of which as different advantages and disadvantages as regards various Canadian tax obligations. In a typical secondment arrangement, the lending employer does not charge a mark-up or profit element to Canco (i.e., any charges are limited to cost recovery), and the CRA has ruled that under such model the lending (non-resident) entity will not be considered to be carrying on business in Canada merely by virtue of having sent employees to Canada on this basis (as opposed to providing services on a for-profit basis). 8 See for example CRA document 2014-0542411R3, 2015.

2. Permanent Establishment in Canada

- A non-resident of Canada who carries on business in Canada and is fiscally resident in a country with a Canadian tax treaty will generally be subject to Canadian income tax on those activities only if they have a “permanent establishment” in Canada.

- A “permanent establishment” is typically a fixed place of business, such as an office, store or worksite. Most treaties carve out specific exceptions for some kinds of fixed places of business (e.g., a storage facility for goods).

- A non-resident does not need to own the fixed place of business: the CRA frequently challenges non-residents whose Canadian subsidiaries make space in their place of business available to the non-resident’s visiting employees.

- A person acting as an employee or agent of a non-resident can also constitute a “permanent establishment” of the non-resident in some cases.

- The Canada-U.S. tax treaty has a specific rule deeming the provision of services in Canada in excess of a set number of days within a given period to constitute a Canadian permanent establishment.

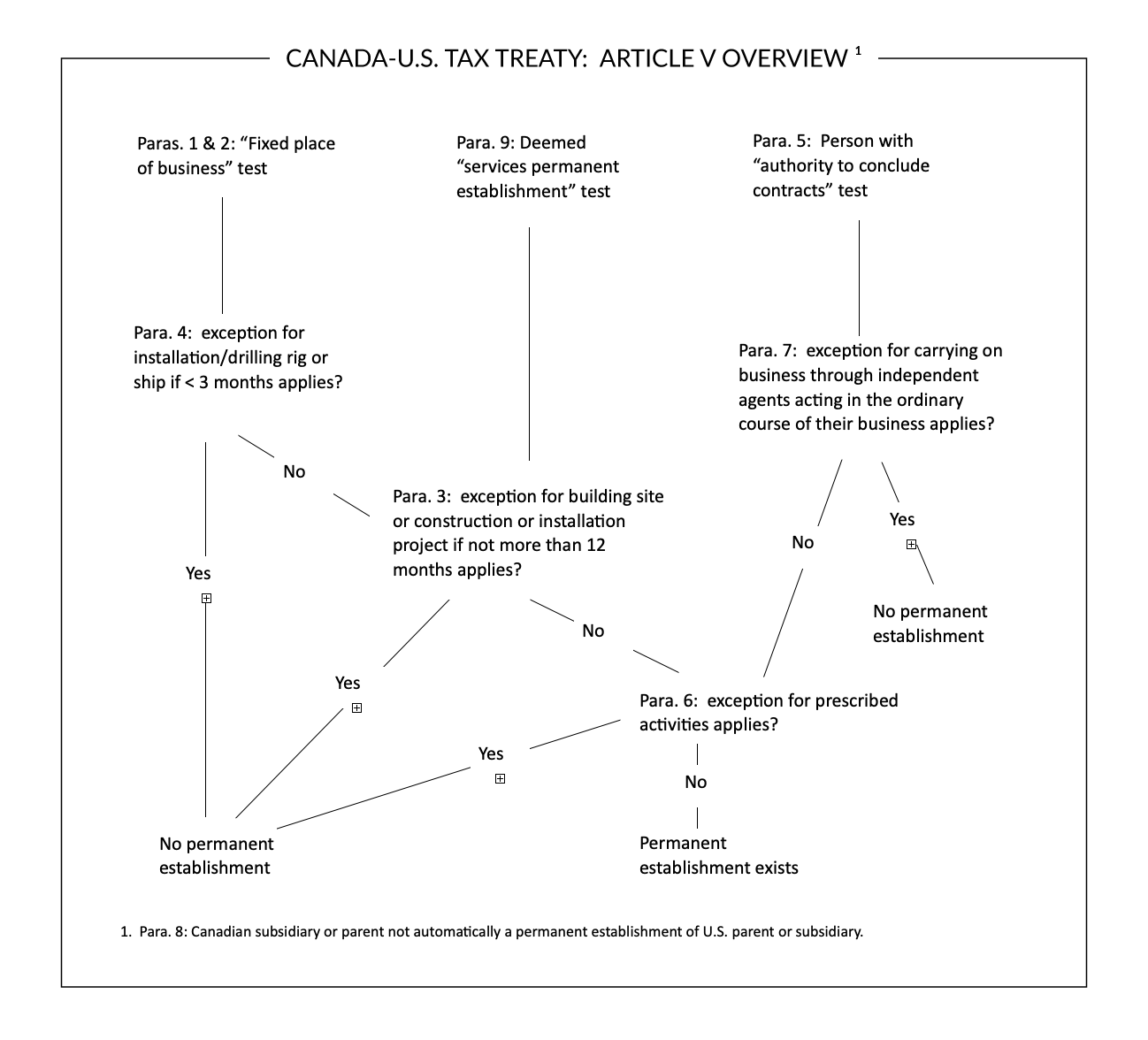

The “permanent establishment” article in each of Canada’s tax treaties is similar in terms of its content and construction, but not identical. Depicted below is the diagrammatic overview of Article V of the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty. In any case however it is always necessary to refer to the text of the particular tax treaty in question. In particular, the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty contains a unique “services permanent establishment” rule in Article V(9). For a discussion of general principles on the interpretation of Canada’s tax treaties, see the Tax Treaties page.

A. Fixed Place of Business

- a branch;

- an office;

- a factory;

- a workshop; and

- a mine, quarry, oil & gas well or similar place of extraction for natural resources.

The key elements of a “fixed place of business” are (1) a geographic location through which the business is carried on by the non-resident, and (2) some degree of regularity or recurrence that goes beyond a temporary presence. 11 For an example of a recurring annual presence (three-week booth operation at an exhibition) being sufficiently “permanent” to constitute a permanent establishment, see Fowler v. Canada, [1990] 2 CTC 2351 (TCC).

In order to be considered a permanent establishment of the non-resident, that non-resident must have some degree of control over the physical location in question. This was established in the case of Dudney v. The Queen, 12 99 DTC 147; affirmed, 2000 DTC 6169 (FCA); leave to appeal denied, 2000 CarswellNat 2662 (SCC). The CRA’s response to the Dudney decision is contained in CRA document TPM-08, dated 5 December 2005. in which the CRA sought to tax a U.S. resident who performed training services in Canada at the business premises of the client (PanCan) of his customer (OSG), based on the assertion that he had a “fixed base regularly available to him in Canada” within the meaning of Article XIV of the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty (since repealed). The Tax Court of Canada described the non-resident’s circumstances as follows:

[4] OSG carried out the contract in part through its own employees, and in part through independent contractors hired for that purpose. The nature and the novelty of the technology was such that it was almost impossible to find qualified instructors in Canada. OSG therefore recruited contractors in the United States. Among those that it recruited was the Appellant, whose residence at that time was in Houston, Texas. It was his expectation when he was hired that he would work for OSG for approximately one year, at which time the project was expected to be completed. However, his contract with OSG provided for termination on 30 days’ notice, mirroring that provision in the PanCan-OSG contract. He understood from the outset that he would be contracted to work at PanCan on the training of its employees.

[5] The work was done on the premises of PanCan in Calgary. The Appellant was at first provided with a small room from which to work. After three months he was moved to a larger room, which he shared with a number of other consultants. Later he was moved to another room in a different building, also occupied by PanCan. For the most part, the actual training, or mentoring, of the PanCan personnel took place in the offices of the people being trained, or in a conference room. Sometimes there would be meetings or consultations in the space provided to the trainers. Their use of that space was strictly limited, however. It was available to them for the purpose of the contract only. They could not conduct any other business from there, they could use the telephone only for business related to the PanCan contract, and their access to the building was controlled by a magnetic card system, and restricted to business hours, on week days only.

[6] The Appellant took no equipment of any kind with him when he went from Houston to Calgary. He had an office in his home in Houston, and from time to time he picked up voice-mail messages from there. He had no letterhead or business cards identifying him as working at PanCan, or elsewhere in Canada. He had no business licence in Calgary, and he was not identified as working in the PanCan premises, either on the directory in the lobby of the building or otherwise. He invoiced OSG on a regular basis for his hours of work.

The Court concluded that the terms “permanent establishment” and “fixed base” were essentially the same, and rejected the CRA’s interpretation that “a non-resident person providing personal services in Canada at any identifiable location, even though it is totally under the control of someone else, has a fixed base available to him, and thus may be subject to tax in Canada on the income from those services.” Instead, the Court held that these terms “are both intended to convey the sense of a place of business which is controlled by and identified with the” non-resident who the CRA is seeking to tax. In this case, these elements were not present:

[14] The Appellant had no control over the premises in which he worked, nor was he identified with them in any way. This was not seriously challenged by the [CRA], whose case was simply that by working at a fixed location in Canada, albeit one dictated and totally controlled by PanCan, the Appellant became subject to taxation here. The Appellant had no freedom to come and go from the building where he worked except during normal business hours, and he could not do any work there, except that done under the contract for PanCan. Any other company wishing to use his services would not be able to find him there, as he was not identified anywhere as working at that location. He had no space in the building that was his exclusively, and in fact the location at which he did his work changed from time to time at the sole discretion of the PanCan personnel. He did not, in my opinion, have a fixed base regularly available to him.

The non-resident’s lack of control over the use of the physical space in question was therefore key to the finding that it did not constitute a fixed place of business of the non-resident. The Federal Court of Appeal upheld the Tax Court’s decision in favour of the taxpayer, following largely the same analysis:

[19] Thus, where a person is denied the benefit of Article XIV on the basis that he has a fixed base regularly available to him in Canada, the question to be asked is whether the person carried on his business at that location during the relevant period. The factors to be taken into account would include the actual use made of the premises that are alleged to be his fixed base, whether and by what legal right the person exercised or could exercise control over the premises, and the degree to which the premises were objectively identified with the person’s business. This is not intended to be an exhaustive list that would apply in all cases, but it is sufficient for this case.

[20] In this case, the Tax Court Judge was correct to consider these factors to be relevant and determinative. The evidence as a whole gives ample support for the conclusion that the premises of PanCan were not a location through which Mr. Dudney carried on his business. Although Mr. Dudney had access to the offices of PanCan and he had the right to use them, he could do so only during PanCan’s office hours and only for the purpose of performing services for PanCan that were required by his contract. He had no right to use PanCan’s offices as a base for the operation of his own business. He could not and did not use PanCan’s offices as his own.

. . .

[24] . . . The analogy suggested by counsel for Mr. Dudney is an apt one. A Canadian lawyer does not acquire a fixed place of business in the office of a client in the United States merely by attending to the client’s affairs there, even if the client insists on the lawyer’s personal presence.

Thus, non-residents seeking to avoid having a Canadian permanent establishment must not have control over a geographic location in Canada through which they conduct their business. When foreign multinationals send employees to Canada, CRA auditors will frequently test the degree to which specific space at the Canadian’s workplace (in particular a Canadian member of the same multinational group) is made available to and put under the control of such visiting employees. The Dudney case identifies the permissible limits to avoid creating a Canadian permanent establishment.

The issue of a “fixed place of business” also arose in a pair of contemporaneous Tax Court decisions in Knights of Columbus v. The Queen 13 2008 TCC 307. (Knights) and American Income Life Insurance Company v. The Queen 14 2008 TCC 306. (AIL). Both cases involved U.S. insurers whose products were sold in Canada by agents who were not employees of the U.S. insurer. The CRA asserted that the U.S. insurers had a Canadian permanent establishment, in part because the home offices of the Canadian agents were (it was alleged) fixed places of business of the U.S. insurers through which their business was carried out.

The Knights case involved a U.S. company whose insurance products were sold via over 200 field agents in Canada. The agreement between Knights of Columbus and the field agents expressly disclaimed any employer-employee relationship between the parties or ability on the part of field agents to bind Knights of Columbus to any insurance policy. Instead, field agents were treated as independent contractors who solicited insurance applications from potential customers and submitted them to Knights of Columbus in the U.S. for acceptance. Field agents worked from their home offices, which were not marked with Knights of Columbus signage and to which Knights of Columbus had no access.

The Court found that field agents’ homes were a place of business with the requisite degree of permanence, but that the business carried on in field agents’ homes was the agents’ business, not the insurer’s:

[78] For the Field Agents’ residences to be considered fixed places of business of the Knights of Columbus, the Knights of Columbus must have a right of disposition over these premises. A right of disposition is not a right of the Knights of Columbus to sell an agents’ house out from under him. The Knights of Columbus might be viewed as having the agents’ premises at its disposal, for example, if the Knights of Columbus paid for all expenses in connection with the premises, required that the agents have that home office and stipulate what it must contain, and further required that clients were to be met at the home office and in fact the Knights of Columbus’ members were met there. In such circumstances, although the Knights of Columbus may not have a key to the premises, the premises might be viewed as being at the disposal of the Knights of Columbus. This would be consistent with Mr. Rosenbloom’s comments.

. . .

[80] Once it has been determined that the Field Agents are independent contractors, which has been agreed, that is, that they are in business on their own account, then it is illogical to find that all the organizing and recordkeeping that they conduct at home is anything other than business activities of their own business. The Knights of Columbus do not have any right of disposition over these premises. The argument that payment of an expense commission creates some such right is not well founded. The expense commission is simply an added commission bearing no relation to actual expenses, which are totally borne by the agent. As well, the agents employ no Knights of Columbus’ staff, have no Knights of Columbus’ signage on the property, are not under the control of the Knights of Columbus for what is required at the home office, and simply provide no access to the Knights of Columbus. The agents do not meet applicants at the premises. The Knights of Columbus make no operational decisions at the Field Agent’s premises. The Knights of Columbus had no officers, directors or employees even visit the agents’ home offices, let alone have any regular access. All risks connected with carrying on business at the home offices are borne by the agents themselves. The agents are not carrying on the Knights of Columbus’ core business from these premises. Their premises cannot therefore be found to be a fixed place of business permanent establishment.

The other insurance case (AIL) also carefully considered the facts regarding home offices maintained by Canadian-based agents, for the purpose of determining whether the U.S.-based insurer had a Canadian permanent establishment. The Tax Court reviewed various sources (including the official Commentary to the OECD Model Income Tax Convention) and articulated a number of important guidelines:

- A permanent establishment requires a fixed place of business meaning:

(a) existence of a place of business;

(b) degree of permanence to such place; and

(c) the carrying on of the business of the enterprise through such fixed place. - The enterprise need not own or lease property for it to be a fixed place of business.

- The premises need not be used exclusively by AIL.

- To determine if AIL’s business is being carried on from the fixed place of business, the following factors should be considered:

– use of premises by AIL

– control by AIL over premises

– legal right to exercise control over premises

– degree to which premises identified with AIL business

– who paid for expenses of premises

– who paid for equipment used at premises

– who made management decisions

– what contracts were concluded from premises

– what AIL products were kept on premises

– did AIL have any Canadian employees

– who bore the risk of the operation from premises

– how many principals were represented by the agent

– were agents subject to detailed instructions or comprehensive control

These cases provide useful guidelines for delineating the circumstances in which a place of business located in Canada will be attributed to a non-resident so as to constitute a permanent establishment of the non-resident. The CRA has ruled favourably that properly structured, the presence of an employee in Canada working from a home office need not create a Canadian permanent establishment for her foreign employer.15 CRA document 2014-0550611R3, 2015.

B. Dependent Agents Concluding Contracts

The “permanent establishment” article of Canada’s tax treaties typically has a paragraph deeming the presence in Canada of a person who concludes contracts for the non-resident to constitute a permanent establishment of the non-resident. An example is Article V(5) of the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty:

5. A person acting in a Contracting State on behalf of a resident of the other Contracting State – other than an agent of an independent status to whom paragraph 7 applies – shall be deemed to be a permanent establishment in the first-mentioned State if such person has, and habitually exercises in that State, an authority to conclude contracts in the name of the resident.

The paragraph 7 reference in Article V(5) is to the following:

7. A resident of a Contracting State shall not be deemed to have a permanent establishment in the other Contracting State merely because such resident carries on business in that other State through a broker, general commission agent or any other agent of an independent status, provided that such persons are acting in the ordinary course of their business.

The distinction between dependent agents and independent agents is also relevant to the “fixed place of business” issue, in terms of identifying whose business (the non-resident’s or the agent’s) is being conducted at the place of business. 16 See the AIL case discussed above, at para. 45. However, if contracts are executed by persons in Canada on the non-resident’s behalf, Article V(5) becomes relevant, and this provision explicitly differentiates between dependent and independent agents. The safe harbour exclusion in Article V(6) discussed below under the heading Preparatory/Auxiliary Activities is also relevant to the issue, as it deems certain persons who would otherwise constitute a permanent establishment of the non-resident not to do so.

The type of contract which a dependent agent must habitually conclude on the non-resident’s behalf is not specified in the text of Canada’s tax treaties, but as a general principle it would seem to be limited to the revenue-generating activities of the business carried on by the non-resident. In the AIL case, the Court cited the following passage from the official Commentary to the OECD Model Convention:

33. The authority to conclude contracts must cover contracts relating to operations which constitute the business proper of the enterprise. It would be irrelevant, for instance, if the person had authority to engage employees for the enterprise to assist that person’s activity for the enterprise or if the person were authorised to conclude, in the name of the enterprise, similar contracts relating to internal operations only. Moreover the authority has to be habitually exercised in the other State; whether or not this is the case should be determined on the basis of the commercial realities of the situation. A person who is authorised to negotiate all elements and details of a contract in a way binding on the enterprise can be said to exercise this authority “in that State”, even if the contract is signed by another person in the State in which the enterprise is situated.

The Court went on to dismiss signing authority on bank accounts and the signing of a collective agreement with Canadian agents as not meeting the required standard to deem a permanent establishment to exist (para. 69).

Similarly, in the Knights of Columbus case the cited the same OECD Commentary as restricting relevant contracts as those “relating to the operations which constitute the business property of [the U.S. insurer].” On the facts of that case, the Court found that a “take-it-or-leave-it” temporary insurance contract which the field agents presented to customers as part of the application for permanent coverage and which became effective immediately upon payment of the initial premium did not come within Article V(5). This conclusion was based on the findings that (1) because the field agent had no authority to negotiate or change the contract terms in any way, he had not concluded the contract in the insurer’s name, and (2) in any event, the temporary insurance contract was not part of the insurer’s business proper and so not within scope of the Article V(5).

How does one distinguish between a dependent agent and independent agent? The Court in AIL cited the following passage from the official Commentary to the OECD Model Tax Convention:

10. The business of an enterprise is carried on mainly by the entrepreneur or persons who are in a paid-employment relationship with the enterprise (personnel). This personnel includes employees and other persons receiving instructions from the enterprise (e.g. dependent agents).

This would seem to indicate that the term “dependent agent” is synonymous with “employee,” and indeed the 1984 U.S. Treasury Department Technical Explanation to Article V(6) seems to use those two terms interchangeably. However, the Court in AIL expressed the view that it was at least possible that an independent contractor (i.e., a non-employee) could be carrying on its own business but doing so as a dependent agent (para. 71). The CRA has also suggested that an arm’s-length Canadian corporation could be a dependent agent of a U.S. customer selling goods out of the Canadian corporation’s warehouse, if the Canadian corporation habitually concluded contracts in the U.S. customer’s name. 17 See CRA document 2004-0070351E5, dated 9 September 2004. See also CRA document TPM-08, dated 5 December 2005: “. . . dependent agents may be individuals or companies.” It would therefore seem the more likely view is that the term “dependent agent” of a non-resident includes but is not necessarily limited to employees of the non-resident.

The distinction between a dependent agent and independent agent was discussed in the AIL decision of the Tax Court, with reference to whether particular agents located in Canada were dependent agents who habitually exercised authority to contract in AIL’s name. The Court determined that in order to be an “independent agent,” a person must do more than simply carry on its own business:

[73] The OECD commentary is clear that the agent must be independent both legally and economically. The commentary states:

38. Whether a person is independent of the enterprise represented depends on the extent of the obligations which this person has vis-à-vis the enterprise. Where the person’s commercial activities for the enterprise are subject to detailed instructions or to comprehensive control by it, such person cannot be regarded as independent of the enterprise. Another important criterion will be whether the entrepreneurial risk has to be borne by the person or by the enterprise the person represents.

…

38.3. An independent agent will typically be responsible to his principal for the results of his work but not subject to significant control with respect to the manner in which that work is carried out. He will not be subject to detailed instructions from the principal as to the conduct of the work. The fact that the principal is relying on the special skill and knowledge of the agent is an indication of independence.

…

38.6. Another factor to be considered in determining independent status is the number of principals represented by the agent. Independent status is less likely if the activities of the agent are performed wholly or almost wholly on behalf of only one enterprise over the lifetime of the business or a long period of time. However, this fact is not by itself determinative. All the facts and circumstances must be taken into account to determine whether the agent’s activities constitute an autonomous business conducted by him in which he bears risk and receives reward through the use of his entrepreneurial skills and knowledge. …

38.7. Persons cannot be said to act in the ordinary course of their own business if, in place of the enterprise, such persons perform activities which, economically, belong to the sphere of the enterprise rather than to that of their own business operations. …

On the facts, the Court found that the Canadian agents were indeed independent, such that whether or not they habitually contracted in AIL’s name, they would not come with the “dependent agent” permanent establishment provision in Article V(5):

[76] . . . I conclude that the PGA and other agents were both legally and economically independent of AIL. The factors I have considered are: firstly, with respect to legal independence:

—The agents in AIL intended that the agents have no legal dependence on AIL.

—AIL has little control, apart from the provisions of certain forms, in how the agents carried on their business.

—AIL had no ownership interest in the agent’s business.

—AIL did not own any capital assets in Canada.

—AIL did not reimburse agents for costs of acquisition or use of assets.

—The workers engaged by the PGAs were the PGA’s, not AIL’s responsibility.

—Agents were not involved in making final decisions on coverage or claims.

—Although agents were part of the collective agreement, the evidence was that this was more a marketing ploy than to create any dependence of the agents legally on AIL.

[77] . . .The factors I rely upon in concluding the agents were economically independent are as follows:

—As commission agents, profit was tied to the agent’s own abilities and results.

—The initial premium created the agent’s income.

—AIL’s income derived from renewals. Dependence in effect is one of AIL on the agents rather than vice versa.

—There are no caps on income nor minimum levels guaranteed by AIL.

—Agents could solicit from anyone, not just PRR leads.

—Apart from PGAs, agents were not required to act exclusively for AIL.

—The agents bore all their own economic risks.

—The fact that PGAs and most agents dealt with only AIL products is not determinative of economic dependency.

—The supply of product in and of itself is not sufficient to create an economic dependence; it was the expansion of the agent’s hierarchy that drove profits.

[78] The Respondent ties the question of economic dependency closely to the concept of integration. Without AIL’s product and support, there would be no profits for the agents: their work was inextricably linked to AIL. I see the situation differently. Certainly, there was product and some support, but the economic success hinged on the agent’s efforts in soliciting and in establishing networks of other agents, activities over which they had complete control.

The case of Knights of Columbus v. The Queen 18 2008 TCC 307. involved a U.S. company whose insurance products were sold via over 200 field agents in Canada. The agreement between Knights of Columbus and the field agents expressly disclaimed any employer-employee relationship between the parties or ability on the part of field agents to bind Knights of Columbus to any insurance policy. Instead, field agents were treated as independent contractors who solicited insurance applications from potential customers and submitted them to Knights of Columbus in the U.S. for acceptance. Field agents worked from their home offices, which were not marked with Knights of Columbus signage and to which Knights of Columbus had no access. All underwriting activity occurred in the U.S., and roughly 90% of insurance applications forwarded to the U.S. by Canadian field agents were approved.

The Court approached the “dependent agent” analysis as follows:

[49] As the dependent agent permanent establishment is the [CRA’s] major assessing position I will address it first. Paragraphs 5, 6 and 7 of Article V of the Canada–U.S. Treaty operate together as follows:

(i) There must be a person who habitually exercises an authority to conclude contracts in the name of the Knights of Columbus.

(ii) That person cannot be an agent of an independent status acting in the ordinary course of his business.

(iii) There will be no dependent agent permanent establishment if the person in Canada engaged solely in certain activities including “advertising, the supply of information, scientific research or similar activities which have a preparatory or auxiliary character”.

The OECD Commentary adds some clarification to these provisions by suggesting that:

(4) The authority to conclude contracts must cover contracts relating to operations which constitute the business proper of the Knights of Columbus. (see paragraph 33 of the OECD Commentary)

In finding that the agents located in Canada did not constitute dependent agents habitually exercising authority to contract on behalf of the insurer, the Court looked very carefully at the details of the relevant contractual arrangements and concluded that they did not meet the threshold required to constitute a permanent establishment.

[50] I am not going to delve into the considerable arguments concerning the dependence or independence of the Field Agents. I have concluded that neither the Chief Agent nor the General Agents are legally or economically dependent on the Knights of Columbus, and are indeed agents of an independent status acting in the ordinary course of their own business. The Field Agents are another matter. They are not, I find, as independent as the agents in American Income Life Insurance Company. However, for purposes of determining whether the Knights of Columbus has a dependent agent permanent establishment, I need not reach a final conclusion of their status. The issue of dependent agent permanent establishment is determined by an examination of the habitual exercise of an authority to conclude contracts. I find none of the Chief Agent, General Agents or Field Agents, even if any of them were dependent, exercise such authority.

. . .

[64] What did the Field Agents do in relation to the Temporary Insurance Agreement? They basically presented it to applicants as an incentive to apply for permanent insurance. If you apply for permanent insurance with the Knights of Columbus, it will provide this temporary coverage pending approval of the permanent insurance. Yes, the Knights of Columbus was bound at the point the Field Agent took the application and initial premiums (or somewhat later depending on medical tests), but it was not the Field Agent who bound them. The Knights of Columbus was bound by the very term of the contract presented to the applicant, terms developed by the Knights of Columbus and not alterable by the Field Agent. Vis-à-vis the temporary insurance, the Field Agent was simply the messenger. Unlike the permanent insurance coverage, which is what the applicant is applying for, and which is not finalized until completion of the underwriting process, the temporary insurance is effective immediately. It is effectively an offer which binds the Knights of Columbus once the applicant accepts by completing an application and depositing the initial premium with the Field Agent. But what is the Knights of Columbus bound to do? It is bound to continue the underwriting process, even after the applicant dies, and to pay out a claim for temporary coverage. The Field Agent’s role in the process surrounding the Temporary Insurance Agreement is minimal. I find the Field Agent is not, in these circumstances, concluding the contract.

Thus, in the Knights case the Field Agents were not found to be independent agents of the U.S. insurer (unlike in AIL), but a close examination of the process by which insurance contracts were concluded showed that those agents (whether or not independent) were not concluding contracts in the insurer’s name. Critically, the Field Agents were not themselves binding the Knights of Columbus, but simply acting as processing intermediaries in the contracts between Knights of Columbus and its customers. As such, it was unnecessary for the Court to determine whether the Field Agents in the Knights case were dependent or independent agents.

The CRA has historically looked to the OECD guidance to determine whether an agent is independent or not, even to the point of accepting that a non-arm’s-length person (such as a subsidiary) can nonetheless be an independent agent of the non-resident. 19 CRA document 9314270, dated 14 June 1993. Criteria applied by the CRA include the following: 20 CRA document 9235160, dated 1 December 1992. See also CRA document 2006-0196221C6, dated 6 October 2006.

- Whether the person is independent of the other person both legally and economically.

- Whether the person is subject to detailed instructions or to comprehensive control by the other person.

- Whether the entrepreneurial risk is borne by the person or the other person the person represents.

- Whether the person sells goods in his own name, rather than in the name of the other person.

- Whether the person receives title to the goods and bears risk of loss upon delivery.

- Whether the person is referred to as an independent contractor rather than as an agent.

- Whether the person must pay the other person for goods received, whether the goods are subsequently sold or not.

- Whether the person acts as an agent for a couple of other persons or many other persons.

- Whether the person has authority to conclude contracts on behalf of the other person.

C. Services PEs: Article V(9) of the Canada-U.S. Treaty

9. Subject to paragraph 3, where an enterprise of a Contracting State provides services in the other Contracting State, if that enterprise is found not to have a permanent establishment in that other State by virtue of the preceding paragraphs of this Article, that enterprise shall be deemed to provide those services through a permanent establishment in that other State if and only if:

(a) those services are performed in that other State by an individual who is present in that other State for a period or periods aggregating 183 days or more in any twelve-month period, and, during that period or periods, more than 50 percent of the gross active business revenues of the enterprise consists of income derived from the services performed in that other State by that individual; or

(b) the services are provided in that other State for an aggregate of 183 days or more in any twelve-month period with respect to the same or connected project for customers who are either residents of that other State or who maintain a permanent establishment in that other State and the services are provided in respect of that permanent establishment.

Expressed in general terms, the test in paragraph 9(a) is directed at situations where a single person is responsible for most of the non-resident’s revenue from the particular business, while the test in paragraph 9(b) applies to larger businesses. The following concepts are applicable to both tests:

- the “services PE” tests in Article V(9) applies to an “enterprise” of Canada or the U.S. that provides services in the other country (not merely to residents of the other country), viz., the service activity occurs in the other country. The CRA considers an “enterprise” to be a particular business carried on by an entity, rather than necessarily the entity itself – that is, if a particular non-resident carries on more than one business, Article V(9) may apply to deem a permanent establishment to exist in respect of one business (the “enterprise”) but not another; 21 CRA document 2013-0475161I7, dated 25 February 2014.

- they apply only to the provision of services by the enterprise, and do not deem a permanent establishment to exist via the provision of services to the enterprise; 22 The U.S. Treasury Technical Explanation states: “Paragraph 9 applies only to the provision of services, and only to services provided by an enterprise to third parties.” The CRA interprets “third parties” as including related parties: CRA document 2009-0319441C6, dated 5 August 2009. and

- where services are provided in such a manner as to come within the exception in Article V(3) for building sites or construction/installation projects of up to one year or the exception in Article V(6) for prescribed activities, no permanent establishment will be created under Article V(9).

The 9(a) Test

Under the 9(a) test, services must be performed by a particular individual who is physically present in Canada for one or more periods adding up to at least 183 days in any 12-month period, during which 183+day period more than 50% of the enterprise’s gross active business revenue consists of income from that individual’s provision of services in Canada. This test is directed at a Dudney-type situation in which a person is physically present in Canada for a large number of days but without her or his own fixed place of business. Note that the 183-day element of the 9(a) test requires only that the relevant individual be physically present in Canada for this number of days, not that services actually be provided on all of those days (this is different from the 9(b) test).

The U.S. Treasury Technical Explanation accompanying the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty 23 Available at https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/treaties/Documents/tecanada08.pdf . Canada’s Department of Finance expressed agreement with the Technical Explanation in News Release 2008-052, July 10, 2008. explains the term “gross active business revenues” as follows:

For the purposes of subparagraph 9(a), the term “gross active business revenues” shall mean the gross revenues attributable to active business activities that the enterprise has charged or should charge for its active business activities, regardless of when the actual billing will occur or of domestic law rules concerning when such revenues should be taken into account for tax purposes. Such active business activities are not restricted to the activities related to the provision of services. However, the term does not include income from passive investment activities.

The 9(b) Test

The 9(b) test requires that the enterprise provide services in the other country (i.e., Canada):

- for 183 or more days in any 12-month period;

- with respect to “the same or connected projects”; and

- for “customers” who are residents of (or have a permanent establishment in) the other country (i.e., Canada).

As noted above, the relevant days for the 183+-day element of the 9(b) test is limited to days where services are actually being provided in Canada, not merely days of physical presence in Canada as in the 9(a) test.

The 9(b) test also requires a specific Canadian “customer” to whom the services are being provided by the U.S. enterprise, unlike the 9(a) test. The U.S. Treasury Technical Explanation states that “The intent of this requirement is to reinforce the concept that unless there is a customer in the other State, such enterprise will not be deemed as participating sufficiently in the economic life of that other State to warrant being deemed to have a permanent establishment.” Thus for example, a U.S. enterprise sending personnel to Canada to perform services on behalf of a U.S. customer (for example, a U.S. law firm sending lawyers to Canada to act on behalf of a U.S.-resident client with no Canadian permanent establishment) will not be deemed to have a Canadian permanent establishment under the 9(b) test.

When a U.S. resident sends its employees to Canada to work for another entity, that U.S. resident will generally thereby be “providing services” in Canada. As noted, in some cases a non-resident’s employees can be “seconded” to a related Canadian entity, such that the Canadian entity becomes the employer of those persons while in Canada, and the activities of those persons are attributed to the Canadian entity rather then the non-resident, viz., they become the Canadian entity’s employees, not the non-resident’s. The CRA appears to take the view that the U.S. resident is thereby providing a service in Canada to a Canadian resident under such arrangements, if it charges a profit margin on the provision of the employee, rather than merely cost recovery. 24 See for example CRA document 2014-0542411R3, 2015. When seeking to avoid the application of the 9(b) test, it is therefore desirable to ensure that secondments are set up without a profit element for the lending U.S. employer.

Subcontractors

The use of subcontractors is an area of uncertainty in interpreting the 9(b) test, in terms of when an enterprise is considering to be providing services in Canada. For example, where a U.S. resident engages a third party to provide services in Canada to a customer of the U.S. resident, will the days in Canada spent by the third party be counted towards the 183-day element of the 9(b) test?

There is no Canadian caselaw on this issue, nor any elaboration in the U.S. Treasury Technical Explanation. The relevant OECD version of the services permanent establishment article and related guidance would attribute the activities of subcontractors to non-residents only when the sub-contractor is not legally and economically independent of the non-resident, 25 Para. 144 of OECD Commentary on Article V. which seems a reasonable distinction. It should be noted however the CRA believes the OECD version of the 9(b) test to be materially different than the 9(b) test in the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty, such that the accompanying OECD guidance “is not of assistance” in interpreting the 9(b) test. 26 CRA document 2011-0426591C6, dated 28 November 2011.

The CRA’s view on this issue appears somewhat expansive. In a technical interpretation involving a U.S. resident (USCo) arranging for services to be provided in Canada to an arm’s-length Canadian customer by various forms of subcontractors, 27 CRA document 2011-0426591C6, dated 28 November, 2011. the CRA’s response treated Canadian subcontractors (whether or not dealing at arm’s length with USCo) as not creating a Canadian permanent establishment for USCo under the 9(b) test, so long as they were paid an arm’s-length fee for doing so. Conversely, the CRA’s position was that using a related U.S. subcontractor to provide services in Canada to USCo’s Canadian customer did result in a Canadian permanent establishment under the 9(b) test for both USCo and the U.S. subcontractor, on the basis that USCo was still “providing” services in Canada to the Canadian customer. While the legal basis for the CRA’s positions in this technical interpretation are not clear, as a practical matter it is very important for U.S. residents subcontracting services to be performed in Canada of the CRA’s views.

Same or Connected Projects

As noted, the 9(b) test applies on the basis of services rendered to Canadian customers “with respect to the same or connected projects.” The meaning of this phrase is discussed at some length in the U.S. Treasury Technical Explanation:

For purposes of determining whether the time threshold has been met, subparagraph 9(b) permits the aggregation of services that are provided with respect to 11 connected projects. Paragraph 2 of the General Note provides that for purposes of subparagraph 9(b), projects shall be considered to be connected if they constitute a coherent whole, commercially and geographically. The determination of whether projects are connected should be determined from the point of view of the enterprise (not that of the customer), and will depend on the facts and circumstances of each case. In determining the existence of commercial coherence, factors that would be relevant include: 1) whether the projects would, in the absence of tax planning considerations, have been concluded pursuant to a single contract; 2) whether the nature of the work involved under different projects is the same; and 3) whether the same individuals are providing the services under the different projects. Whether the work provided is covered by one or multiple contracts may be relevant, but not determinative, in finding that projects are commercially coherent.

The aggregation rule addresses, for example, potentially abusive situations in which work has been artificially divided into separate components in order to avoid meeting the 183-day threshold. Assume for example, that a technology consultant has been hired to install a new computer system for a company in the other country. The work will take ten months to complete. However, the consultant purports to divide the work into two five-month projects with the intention of circumventing the rule in subparagraph 9(b). In such case, even if the two projects were considered separate, they will be considered to be commercially coherent. Accordingly, subject to the additional requirement of geographic coherence, the two projects could be considered to be connected, and could therefore be aggregated for purposes of subparagraph 9(b). In contrast, assume that the technology consultant is contracted to install a particular computer system for a company, and is also hired by that same company, pursuant to a separate contract, to train its employees on the use of another computer software that is unrelated to the first system. In this second case, even though the contracts are both concluded between the same two parties, there is no commercial coherence to the two projects, and the time spent fulfilling the two contracts may not be aggregated for purposes of subparagraph 9(b). Another example of projects that do not have commercial coherence would be the case of a law firm which, as one project provides tax advice to a customer from one portion of its staff, and as another project provides trade advice from another portion of its staff, both to the same customer.

Additionally, projects, in order to be considered connected, must also constitute a geographic whole. An example of projects that lack geographic coherence would be a case in which a consultant is hired to execute separate auditing projects at different branches of a bank located in different cities pursuant to a single contract. In such an example, while the consultant’s projects are commercially coherent, they are not geographically coherent and accordingly the services provided in the various branches shall not be aggregated for purposes of applying subparagraph 9(b). The services provided in each branch should be considered separately for purposes of subparagraph 9(b).

D. Exception for Prescribed, Preparatory and Auxiliary Activities

6. Notwithstanding the provisions of paragraphs 1, 2, 5 and 9, the term “permanent establishment” shall be deemed not to include a fixed place of business used solely for, or a person referred to in paragraph 5 engaged solely in, one or more of the following activities:

(a) the use of facilities for the purpose of storage, display or delivery of goods or merchandise belonging to the resident;

(b) the maintenance of a stock of goods or merchandise belonging to the resident for the purpose of storage, display or delivery;

(c) the maintenance of a stock of goods or merchandise belonging to the resident for the purpose of processing by another person;

(d) the purchase of goods or merchandise, or the collection of information, for the resident; and

(e) advertising, the supply of information, scientific research or similar activities which have a preparatory or auxiliary character, for the resident.

The 1984 version of the Technical Explanation issued by the U.S. Treasury Department interpreting the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty indicates that “Combinations of the specified activities have the same status as any one of the activities. Thus, unlike the OECD Model Convention, a combination of the activities described in subparagraphs 6(a) – (e) need not be of a preparatory or auxiliary nature (except as required by subparagraph 6(e)) in order to avoid the creation of a permanent establishment.”

A third-party storage facility that holds inventory owned by a non-resident and fulfils instructions to deliver those goods to Canadian customers has been held to come within the exclusion in subparagraphs 6(a) and (b). 28 CRA document 2010-0384901E5, dated 27 January, 2011. In CRA document 2012-0438691E5, dated 17 October 2012, the CRA made the further statement that “if a non-resident is engaged in the mere storage of inventory in an unaffiliated company’s warehouse, this factor alone would not result in a conclusion that the non-resident is carrying on business in Canada.” In the Knights of Columbus case discussed above, the Tax Court (had it been necessary) would have concluded that the activities of field agents located in Canada came within the exclusionary rule in Article V(6) of the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty on the basis that “the activities the Field Agent carries on from home consist, I find, solely of storage, collection of information, supply of information and similar auxiliary or preparatory activities.”

E. Using Canadian Corporations for In-Canada Activities

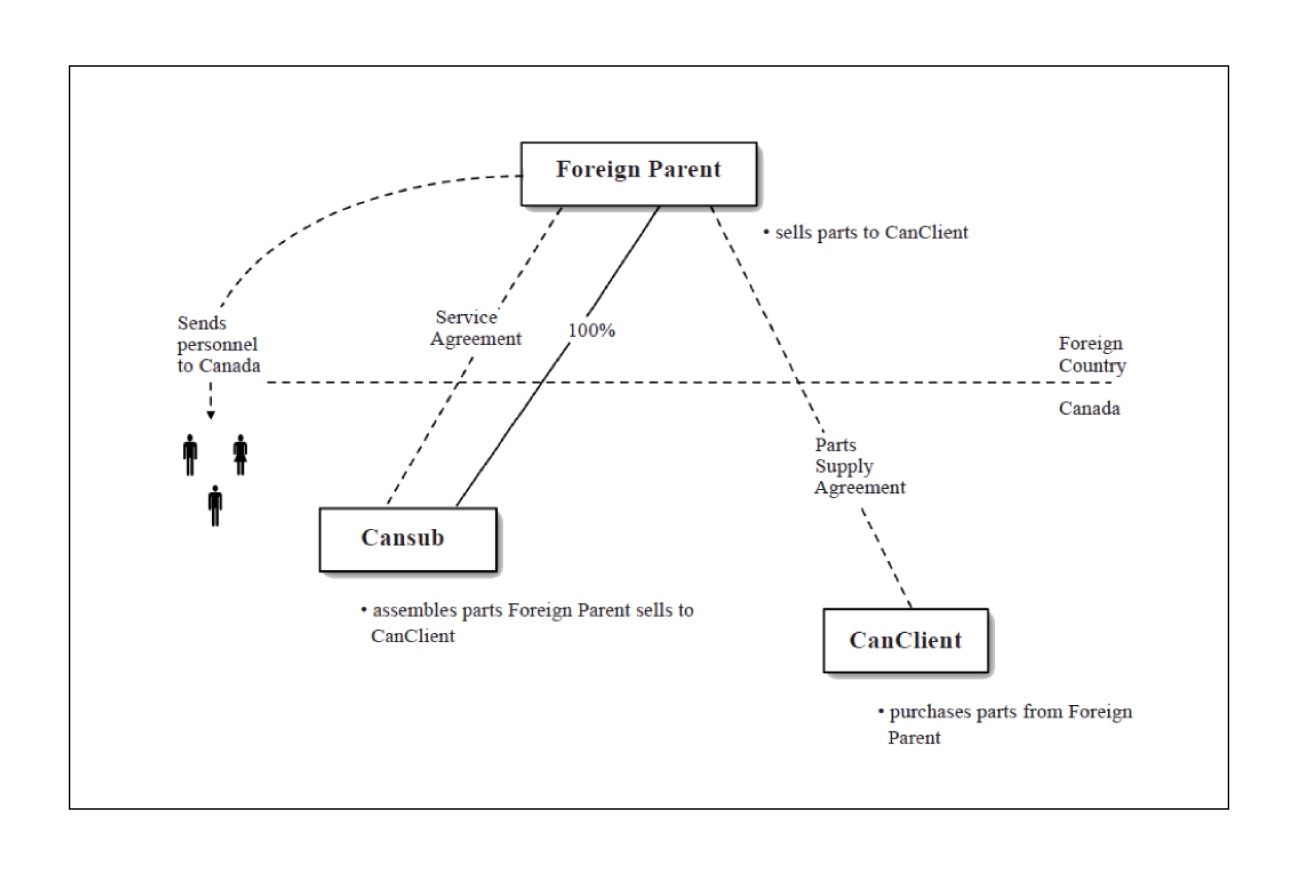

A 2011 advance tax ruling 29 CRA document 2011-0396421R3, dated 14 July 2011. issued by the CRA illustrates this scenario, whereby Foreign Parent carried on a manufacturing and distribution business that involved sales to an arm’s-length Canadian customer (CanClient). Foreign Parent entered into a Services Agreement with its wholly-owned Canadian subsidiary (Cansub) to have Cansub assemble (and in some cases manufacture) and deliver the parts Foreign Parent sold to CanClient (as these activities could be done more efficiently in Canada). Foreign Parent frequently had employees in Canada supervising Cansub personnel or dealing with CanClient. By very carefully structuring its arrangements, Foreign Parent was able to get the CRA to rule that these activities would not result in Foreign Parent carrying on business in Canada through a Canadian PE.

The key points of the arrangement between the parties were as follows:

- Foreign Parent made sure that its agreements with Cansub identified Cansub as an independent contractor engaged in its own business, i.e., not Foreign Parent’s agent acting as part of Foreign Parent’s business.

- These agreements made clear that Cansub did not have authority to receive orders, negotiate with customers, or conclude contracts on behalf of Foreign Parent, or assume any obligation on behalf of Foreign Parent. They also made clear that Cansub would not hold itself out as an agent, a representative or a partner of Foreign Parent.

- Critically, Foreign Parent ensured that it would not have its employees physically present in Canada for more than 90 days in any 12-month period, and that in the event that it became necessary to have someone physically in Canada for more than 90 days such persons would be formally seconded to Cansub. This very likely allowed the CRA to conclude that whatever physical presence Foreign Parent had in Canada did not have a sufficient degree of permanence to rise to the level of a “permanent establishment”.

- Foreign Parent did not own or lease any real property in Canada, and steps were taken to ensure that no specific portion of Cansub’s facilities were identifiable as Foreign Parent’s business location or reserved exclusively for use of visiting Foreign Parent employees.

While this ruling does not create hard-and-fast benchmarks that necessarily govern in all circumstances (particularly as each tax treaty is somewhat different), it identifies many of the key things that non-residents with Canadian subsidiaries and clients can do to minimize the risk of being taxable in Canada via a Canadian permanent establishment.

3. Sending Employees to Canada

- A non-resident that sends its own employees to Canada risks creating a Canadian taxable nexus for itself, in terms of being considered to carry on business in Canada and/or having a permanent establishment in Canada

- Moreover, the non-resident employee may become taxable in Canada (even if not here long enough to become a resident of Canada), by virtue of performing employment services while in Canada.

- A non-resident whose employees perform their jobs while in Canada has an obligation to withhold and remit Canadian taxes from the pay of those employees, subject to certain forms of administrative relief.

- Under a “secondment” arrangement, a non-resident can loan its employees to a Canadian entity, which thereby becomes the employer and assumes the related Canadian tax liabilities and obligations.

- Employees performing services in Canada are obligated to contribute to the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) and Employment Insurance (EI) programs, subject to potential relief under a treaty between Canada and their home country.

Distinguishing Employees from Independent Contractors

- employees are generally entitled to claim fewer deductions in computing income than are independent contractors;

- favourable rules on the taxation of stock options are limited to employees;

- employers have obligations to withhold and remit from compensation paid to an employee in respect of income tax, CPP premiums and EI premiums, as well as themselves being required to pay CPP and EI premiums in respect of employees (similar considerations arise in respect of provincial payroll taxes);

- only employees can receive EI benefits on cessation of employment;

- employees are generally taxed on a cash basis (i.e., as amounts are received), whereas independent contractors include amounts in income on an accrual basis (i.e., when earned);

- employees have different tax return filing deadlines than do independent contractors;

- independent contractors may be liable to pay taxes in quarterly instalments prior to filing tax returns, and to charge GST/HST on the services they render;

- in a cross-border context, tax treaties allow the source country (i.e., the place where services are being performed) greater rights to tax employees than to tax independent contractors (i.e., Article XV versus Article VII of the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty).

As such, it is important to both the payer and the recipient to establish whether or not a person rendering services to another entity is in fact an employee of that entity.

The ITA itself is of little assistance in distinguishing employees from others, in that it defines the term “employee” merely as including an “officer,” and defines “employment as follows:

employment means the position of an individual in the service of some other person (including Her Majesty or a foreign state or sovereign) and servant or employee means a person holding such a position

There is however a wealth of caselaw on this subject. The leading case on this topic is the Supreme Court of Canada’s decision in 671122 Ontario Ltd. by Sagaz Industries Canada Inc.. 30 2001 SCC 59. While not itself a tax case, in Sagaz the SCC reviewed and adopted the leading tax jurisprudence on distinguishing between employees and independent contractors 31 Weibe Door Services Ltd. v. M.N.R., [1986] 3 F.C. 533 (FCA). (and in so doing confirmed that there is generally little or no difference between the tax and commercial law definitions of the term “employee”).

The SCC summarized the Canadian jurisprudence on this question as follows:

46 In my opinion, there is no one conclusive test which can be universally applied to determine whether a person is an employee or an independent contractor. Lord Denning stated in Stevenson Jordan, supra, that it may be impossible to give a precise definition of the distinction (p. 111) and, similarly, Fleming observed that “no single test seems to yield an invariably clear and acceptable answer to the many variables of ever changing employment relations . . .” (p. 416). Further, I agree with MacGuigan J.A. in Wiebe Door, at p. 563, citing Atiyah, supra, at p. 38, that what must always occur is a search for the total relationship of the parties:

[I]t is exceedingly doubtful whether the search for a formula in the nature of a single test for identifying a contract of service any longer serves a useful purpose…. The most that can profitably be done is to examine all the possible factors which have been referred to in these cases as bearing on the nature of the relationship between the parties concerned. Clearly not all of these factors will be relevant in all cases, or have the same weight in all cases. Equally clearly no magic formula can be propounded for determining which factors should, in any given case, be treated as the determining ones.

47 Although there is no universal test to determine whether a person is an employee or an independent contractor, I agree with MacGuigan J.A. that a persuasive approach to the issue is that taken by Cooke J. in Market Investigations, supra. The central question is whether the person who has been engaged to perform the services is performing them as a person in business on his own account. In making this determination, the level of control the employer has over the worker’s activities will always be a factor. However, other factors to consider include whether the worker provides his or her own equipment, whether the worker hires his or her own helpers, the degree of financial risk taken by the worker, the degree of responsibility for investment and management held by the worker, and the worker’s opportunity for profit in the performance of his or her tasks.

48 It bears repeating that the above factors constitute a non-exhaustive list, and there is no set formula as to their application. The relative weight of each will depend on the particular facts and circumstances of the case.

To a significant extent the courts will look to the contract between the parties themselves and see what their intentions were, i.e., did they intend there to be an employer-employee relationship. While merely labelling a relationship as being one of independent contractor-customer or employee-employer will not overcome the parties’ actual conduct if that conduct is inconsistent with the way the parties have characterized their relationship, it is clear from the caselaw that the courts will put a significant amount of weight on the parties’ characterization of their relationship. This can be seen in cases such as is Wolf v. Canada 32 2002 FCA 96. and 1392644 Ontario Inc. v. M.N.R., 33 2013 FCA 85. where the Federal Court of Appeal described the process as consisting of two steps: (1) first ascertaining the subjective intentions of the parties (i.e., from their contract and their actual conduct), and (2) then ascertaining “whether an objective reality sustains the subjective intent of the parties”.

Thus, the principal used by the courts to distinguish between employees and independent contractors are the following:

- whether the parties have identified the service provider as being an employee or an independent contractor;

- the degree of control exercised by the payer over the service provider (i.e., directing them to achieve a specific result, as opposed to also controlling how they achieve it);

- whether the service provider owns the tools required to perform the service;

- whether the service provider enjoys the typical benefits of an employee (e.g., protection from termination, vacation/sick pay, etc.);

- whether the service provider works for more than one customer;

- the extent to which the service provider bears the financial risk from the activities; and

- whether the worker is reimbursed for expenses

The CRA’s guidance on this issue is RC4110, Employee or Self-Employed?, which largely follows the same process as is laid out in the caselaw. Other CRA resources of interest on this topic include CRA Folio S4-F14-C1, Artists and Writers

Employee Taxation in Canada: ITA

A resident of Canada will be taxable on her worldwide income from all sources, including employment rendered in Canada or elsewhere. Conversely, a non-resident of Canada earning employment income is subject to Part I Canadian income tax only in respect of employment services rendered “in Canada.” Non-residents who are employed “in Canada” during a given year must therefore separate their income from such “in Canada” employment from any amounts earned from employment outside of Canada. An allocation of income between Canada and another jurisdiction is generally based on a method that is reasonable in all of the particular facts and circumstances (e.g., time spent in different countries)

An employee’s income for a taxation year is defined as “the salary, wages and other remuneration, including gratuities, received by the taxpayer in the year” (note the use of the term “received” rather than “receivable”) [s. 5 ITA]. The ITA goes on to include various specific items within an employee’s income for the year, including:

- the value of board, lodging and other benefits of any kind whatever received or enjoyed by the taxpayer (or a non-arm’s-length person) in the year, subject to certain exceptions;

- director’s fees; and

- benefits received under various forms of employee benefit plans. [s. 6 ITA]

Special (and beneficial) rules apply to employees who are granted stock options [s. 7], which in general terms have the effect of (1) ignoring the grant of the option as a taxable event, and (2) on the exercise of the option, reducing the income arising from (or in some cases deferring recognition of) the resulting benefit. Employees are essentially precluded from claiming any deductions in computing income other than those specifically listed in the ITA [s. 8].