Payments From Canada

Table of Contents

1. Part XIII Withholding

- Part XIII withholding applies on various forms of payment (generally of a passive nature) made to non-residents of Canada by a Canadian resident (or deemed Canadian resident).

- The basic rate of Part XIII tax is 25% of the gross payment (no deductions permitted), subject to reduction under an applicable tax treaty (if any) between Canada and the recipient’s country of residence.

- The payer of an amount to which Part XIII tax applies is obligated to withhold and remit to the CRA the amount of the tax owing, and is jointly liable with the recipient for such tax (and potentially interest and penalties), with no time limit for the CRA to re-assess.

- Part XIII withholding applies where an amount is paid or credited to the non-resident, viz., on a cash basis, not as amounts accrue, although in certain cases the ITA deems amounts to have been paid for this purpose.

- various technical issues and anti-avoidance provisions exist throughout Part XIII (e.g., rules deeming persons to be Canadian residents deeming amounts to have been paid, and ignoring the actual recipient of payments or the actual legal character of amounts paid), creating many potential traps.

Non-residents are subject to Canadian withholding tax (also called Part XIII tax) on payments of passive, investment-type income from Canada (typically where the payer is a Canadian resident). The most prominent examples of income subject to Part XIII tax are dividends, interest (if paid between non-arm’s-length persons or if the interest is participating interest), rents and royalties. The rate of tax is 25% of the gross amount of the payment, with no deductions permitted. If the recipient is resident in a country that has a tax treaty with Canada, in most cases that treaty will reduce (or in some cases eliminate) Canadian Part XIII withholding tax. Thus, the analysis requires two steps:

- determine whether Part XIII applies under the ITA (including with reference to exceptions established under the Income Tax Regulations); and

- determine whether a tax treaty applies to provide relief.

Note that even if the non-resident recipient is economically indifferent to whether or not Canadian withholding tax applies because its home country tax is reduced dollar-for-dollar via a foreign tax credit for all Canadian withholding tax paid, it is still essential to determine whether (and at what rate) Canadian withholding tax applies. If insufficient Part XIII tax is remitted to the CRA, the Canadian payer is liable for the deficiency, plus interest and penalties.

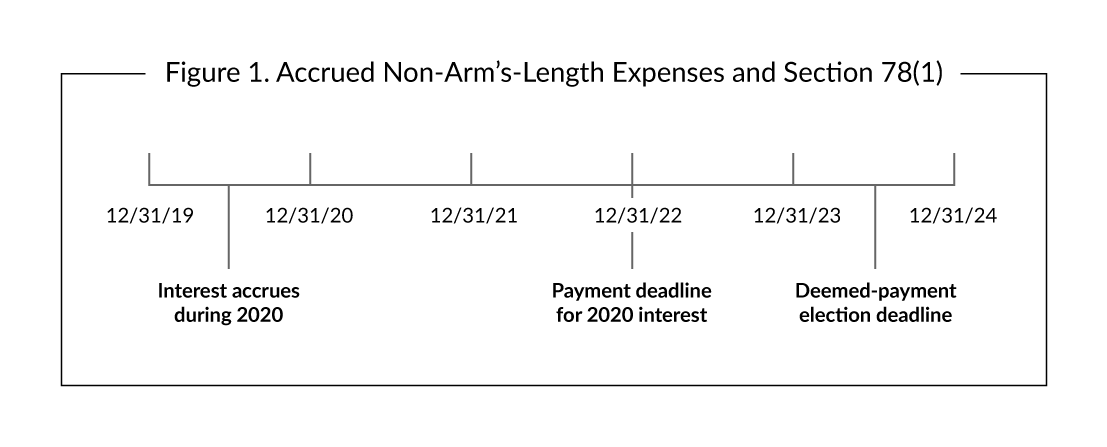

As noted elsewhere, there is a limit to how long expenses owed to a non-arm’s-length person can remain unpaid before the Canadian debtor’s deduction is reversed (this prevents the debtor from claiming deductions on an accrual basis while indefinitely deferring payment of withholding tax, which applies upon payment). An expense incurred by the taxpayer owing to a non-arm’s-length person in one tax year must be paid by the end of the payer’s second following tax year. If it remains unpaid by that time, the amount is added back into the payer’s income in the immediately following tax year, effectively reversing any deduction previously taken (see Figure 1).

General Principles

The basic principle underlying Part XIII withholding is to impose tax on a non-resident’s Canadian-source income of a passive, investment-type nature, i.e., income that typically will not fall into the scope of what non-residents are taxable under Part I on (income from carrying on business in Canada, performing employment services in Canada or gains from taxable Canadian property). Various aspects of this general rule that require further elaboration:

- which payers Part XIII applies to;

- the application of Part XIII to partnerships (both as payers and recipients);

- exceptions to Part XIII withholding; and

- administration of Part XIII tax.

Which Payers Does Part XIII Apply To?

The “Canadian source” element of Part XIII tax is created via the identity of the payer to whom Part XIII tax applies: residents of Canada (or in the case of dividends, corporations resident in Canada). However Part XIII tax can also apply to a non-resident payer.

s. 212(13) lists a variety of payments in respect of which a non-resident payer is deemed to be a resident of Canada for purposes of s. 212, with the result that Part XIII withholding may apply on a payment from one non-resident to another. The payments included in 212(13) include:

- rent for the use in Canada of property;

- interest on a mortgage or other debt secured by an interest in Canadian real property, to the extent such interest is deductible in computing the non-resident’s income subject to Part I tax; and

- amounts payable in respect of a “restrictive covenant” (see Other Payments, below), to the extent such amounts relate to the acquisition or provision of property or services (1) in Canada, (2) by a Canadian resident, or (3) in respect of a “taxable Canadian property.”

Similarly, a non-resident payer is deemed to be a Canadian resident in respect of an amount paid that is deductible in computing the non-resident’s taxable income earned in Canada from a source that is not exempt from Canadian tax under a tax treaty (s. 212(13.2)). Non-residents are also deemed to be residents of Canada in respect of certain specific payments described in Part XIII, making it important to carefully review the legislation. For example, non-residents are deemed to be residents of Canada under s. 214(9) in respect of the assignment or transfer of certain debt obligations.

Partnerships

A partnership is deemed to be a person resident in Canada for purposes of Part XIII, to the extent that it pays amounts to a non-resident that are deductible in computing the partnership’s income from a source in Canada (s. 212(13.1)). This has the effect of expanding the scope of payers to whom Part XIII tax applies to include partnerships (which are not otherwise treated as “persons” for most ITA purposes) with Canadian-source income.

Conversely, where a partnership receives a payment described in Part XIII, the partnership is itself deemed to be a non-resident person (i.e., such that Part XIII withholding applies to the payment) unless the partnership is a “Canadian partnership.” A “Canadian partnership” is defined (s. 102) as a partnership all the members of which are Canadian residents for ITA purposes (whether the partnership is created under the laws of Canada or a foreign jurisdiction is irrelevant). Hence, partnerships considering the admission of a partner who is (or may become in the future) a non-resident for ITA purposes should be aware of the potential withholding obligations this may create on persons making payments to the partnership. (Note: for purposes of applying a tax treaty to an amount paid by to a partnership, the general rule is to look through the partnership to the partners themselves, who may or may not be entitled to treaty relief depending on their particular circumstances).

Exceptions

Regulation 805 creates an exception to Part XIII for non-residents that carry on business in Canada to the extent of amounts reasonably attributable to a permanent establishment in Canada through which the business is carried on. 1 For this purpose the term “permanent establishment” is defined in Regulation 8201. In this manner, such amounts generally subject to Part I tax in Canada will not also be subject to Part XIII tax. Conceptually similar exceptions apply for amounts earned in connection with a “Canadian resource property” held as part of a business (i.e., mining, oil & gas, pipelines: Regulation 805(b)) and registered non-resident insurers (Regulations 800-804).

Non-residents earning rent from real property (i.e., an interest in land) in Canada or timber royalties can elect under s. 216 to be taxed under Part I on such amounts instead of under Part XIII (i.e., on net income at Part I rates, rather than on the gross payment at Part XIII rates). The s. 216 election is explained in CRA Guide 4144. A conceptually similar election is applicable to non-residents receiving payments in respect of the provision in Canada of acting services in a film or video production.

Administration

Part XIII withholding tax operates by creating an obligation on the payer to withhold from the payment and remit to the CRA the required amount of tax. The withholding mechanism is a reflection of the practical difficulty of collecting tax from a non-resident who may have few or no assets in Canada: instead, a joint obligation for the tax is created by including the payer, who is either a Canadian resident or a non-resident with some substantive economic connection to Canada.

Part XIII tax applies where the payer “pays or credits” the relevant amounts “as, on account of or in lieu of payment of, or in satisfaction of” to a non-resident. Thus, the charging provision encompasses more than the actual payment of the relevant amounts in the form originally envisioned. For example, setting funds aside and making them unconditionally available to the recipient would be considered “crediting” the relevant amount to the non-resident, while a mere journal entry with nothing more would not be. 2 See Compagnie Miniere Quebec Cartier v. M.N.R., 84 DTC 1348 (TCC). See also CRA Information Circular IC77-16R4. para. 5. Simply declaring that the recipient “shall have the right at any time to require payment of the amount” does not result in it being “paid or credited.” 3 See Canada v. Lewin, 2012 FCA 279. The CRA has taken the (correct) position that applying an amount payable to reduce a liability of the recipient owing to the payer would be considered “crediting” the amount and thereby triggering Part XIII tax. 4 CRA document 2013-0499621E5, dated July 14, 2015.

The key administrative elements of Part XIII tax are as follows:

- a payer who fails to deduct or withhold as required is itself liable for the non-resident’s Part XIII tax owing, and is entitled to deduct or withhold from any amount payable to the non-resident (or otherwise recover) any Part XIII tax it pays on the non-resident’s behalf (s. 215(6)). A comparable rule applies to amounts deducted or withheld by the payer but not remitted to the CRA as required (s. 227(9.4));

- an amount deducted or withheld during a particular month must be received by the CRA by the 15th day of the following month to be considered timely;

- a person who fails to deduct and withhold an amount as required is liable to a penalty of 10% of the amount, or 20% if the failure is attributable to gross negligence and the same payer has already been penalized for a previous failure in the same calendar year (s. 227(8)). In such circumstances, interest on the amount that should have been deducted begins to run on the day the deduction or withholding should have been made (s. 227(8.3));

- similarly, a person who has deducted or withheld an amount but has failed to remit it as required is liable to a penalty of up to 10% of the amount, or 20% if the failure is attributable to gross negligence and the same payer has already been penalized for a previous failure in the same calendar year (s. 227(9)). In such circumstances, interest on the amount that should have been deducted begins to run on the day the deduction or withholding should have been made (s. 227(9.2)).

- no legal action may be taken against any person for deducting or withholding in compliance (or intended compliance) with their ITA obligations (s. 227(1)), and any agreement not to withhold as required under the ITA is void (s. 227(12));

- payments by an agent of the debtor or to an agent of the recipient carry the deduction and withholding obligation otherwise imposed on the debtor (ss. 215(2) and (3)); and

- there is no time limit on the CRA’s right to re-assess a person for amounts owing under Part XIII, including interest and penalties (ss. 227(10) and (10.1)).

In addition to the obligation to withhold and remit, payments to which Part XIII applies also require the payer to comply with a notification and filing requirement (NR4 information slips and returns). The CRA webpage on Part XIII tax contains various resources relating to Part XIII tax, most notably Guide T4601. This publication provides further information on a number of administrative aspects of Part XIII compliance, including how to set up a non-resident tax account with the CRA for remitters, how to complete NR4 slips, and contact information for the relevant branch of the CRA. The CRA website also has a “Non-Resident Tax Calculator” for the convenience of non-residents entitled to benefits under a tax treaty.

Dividends

Dividends paid or credited to a non-resident by a Canadian-resident corporation are subject to Part XIII withholding tax. This includes either taxable dividends or capital dividends, as well as stock dividends (s. 212(2)).

The ITA deems a variety of amounts to be dividends for tax purposes (either generally or for Part XIII), including the following:

- benefits conferred by a corporation on its shareholders (or persons related thereto) under s. 15(1) (s. 214(3)(a));

- the amount of a loan made by a corporation to a shareholder (or person related thereto) described in s. 15(2) (s. 214(3)(a));

- an increase in the PUC of a Canadian-resident corporation’s shares unaccompanied by an increase in its net assets (s. 84(1));

- where a Canadian-resident corporation distributes property to its shareholders on the winding up, discontinuance or reorganization of its business (including on a wind-up of the corporation itself), the excess of the amount distributed to shareholders by the corporation over the amount by which the PUC of its shares is reduced (s. 84(3));

- when a corporation resident in Canada redeems, acquires or cancels its shares, the excess of the amount paid by the corporation over the PUC of those shares (s. 84(3));

- interest that is disallowed as a deduction under the thin capitalization rules and has been paid (or deemed to be paid) by a Canadian-resident corporation;

- an amount deemed to be a dividend under the foreign affiliate dumping (FAD) rules;

- as a “secondary adjustment,” the net amount of a transfer pricing adjustment assessed against a Canadian-resident corporation; and

- on a sale of shares of a Canco by a non-resident to another Canco with which the non-resident does not deal at arm’s length, the amount by which any consideration received by the non-resident (other than shares of the purchaser) exceeds the PUC of the shares being transferred (s. 212.1).

Certain dividend compensation payments made under a securities lending arrangement are exempted from Part XIII (s. 212(2.1)). Virtually all of Canada’s tax treaties reduce the rate of Part XIII dividend withholding tax for residents of treaty countries that meet the standard for claiming treaty benefits to rates ranging from 5% – 15%.

Interest

The ITA imposes Part XIII interest withholding tax only on:

- interest (other than “fully exempt interest”) 5 “Fully exempt interest” is interest on a debt owing by the government of Canada, a province or a municipality (or certain public bodies) or a debt guaranteed by the government of Canada, interest paid to certain international organizations, and certain other amounts described in s. 212(3). that is paid to a non-resident who does not deal at arm’s length with the debtor (or paid to a non-resident in respect of a debt owing to a creditor who does not deal at arm’s length with the debtor, if the debt principal and interest have been bifurcated); and

- participating interest.

“Interest” under Canadian law is generally considered to be an amount that (1) is calculated by reference to an underlying principal amount of debt, (2) as compensation for the use of money, and (3) accruing from day to day.

A non-resident may deal not at arm’s length with a payer of interest either by virtue of being related to the payer (e.g., a corporation and the person who controls it), or as a result of being considered not to deal at arm’s length as a question of fact in the particular circumstances at hand. Such de facto non-arm’s length status has been found to exist in situations where one party is under the influence or control of the other, where a common mind directs the bargaining for both parties to a transaction, or where parties act in concert without separate interests (see for example Canada v. McLarty, 2008 SCC 26, at par. 62). The CRA announced in 2020 that it no longer seeks to impose interest withholding tax on imputed interest on outbound non-arm’s-length swap payments. 6 2020 IFA Roundtable, question 2.

Part XIII tax will apply (subject to treaty relief) where the actual recipient of the interest deals at arm’s length with the payer but the lender (i.e., the person to whom the principal is owed) does not. The ITA was amended in 2011 to address cases where a creditor not dealing at arm’s-length with the debtor sells the interest entitlement to an arm’s-length person while continuing to hold the entitlement to receive the principal amount on maturity (see Lehigh Cement Limited v. Canada, 2010 FCA 124).

“Participating interest” is interest all or any portion of which is contingent or dependent on the use of or production from property in Canada or computed by reference to revenue, profit, cash flow, commodity price or similar criterion (s. 212(3)). Certain kinds of “fully exempt interest” and interest on an indexed debt obligation are excluded from this definition. Problems with “participating interest” frequently arise in the context of convertible or exchangeable debentures, where the amount received by the creditor on a transfer, assignment or redemption of the debt (which is often deemed to be a payment of interest for withholding tax purposes) varies with reference to changes in the value of an underlying property. 7 See in this regard CRA document 2013-0509061C6, dated November 26, 2013. Caution should be exercised in any case in which interest is computed other than on the basis of a percentage of the debt’s principal amount.

The ITA contains a variety of deeming rules relating to interest and Part XIII withholding that create traps for the unwary. For example,

- as noted elsewhere, interest that has been disallowed as a deduction under the thin capitalization rules is deemed to be a dividend (and not interest) for Part XIII purposes;

- amounts paid to a non-resident as a fee for guaranteeing repayment of a debt owing by a Canadian resident are deemed to be interest for Part XIII purposes (s. 214(15)(a));

- amounts paid to a non-resident as a fee for agreeing to lend or make money available to a Canadian resident (e.g., a standby fee) are deemed to be interest for Part XIII purposes, if the non-resident would be subject to Part XIII tax on interest payable under a debt issued under the terms of such agreement (s. 214(15)(b)); and

- various transfers and assignments (including redemptions) of debt obligations between Canadian residents and non-residents of Canada are deemed to constitute the payment of interest (ss. 216(6)-(10)).

In addition, Part XIII withholding in respect of interest is supported by a complex anti-avoidance regime discussed below. These rules require one to look “behind” the direct recipient of interest from the Canadian payer in circumstances where (1) that recipient has a relationship with another party that is connected with recipient’s receivable from the Canadian payer and (2) that other party would be subject to higher Canadian interest withholding tax than the direct recipient (e.g., back-to-back loans).

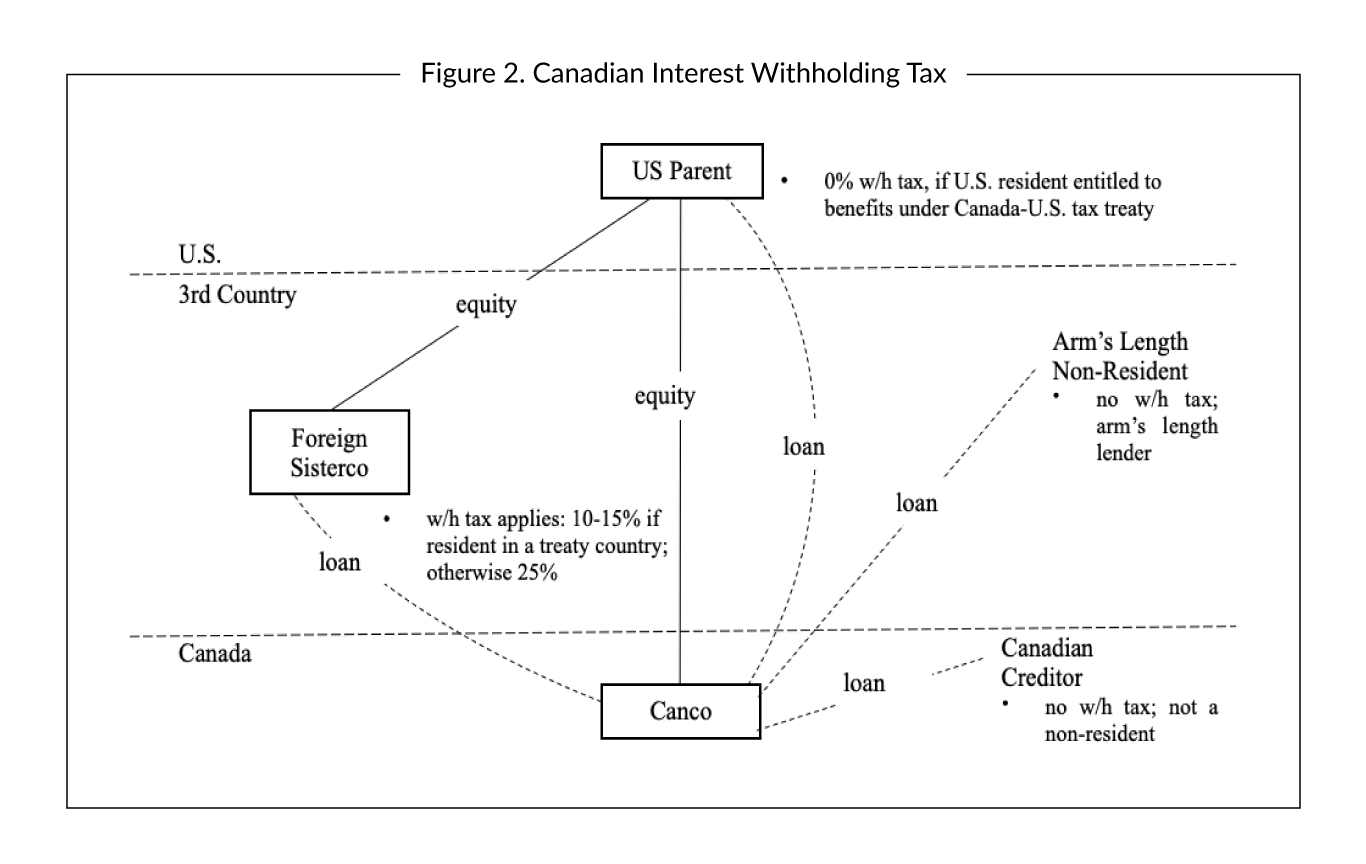

Virtually all of Canada’s income tax treaties substantially reduce the rate of interest withholding tax. The only Canadian tax treaty that reduces the rate of interest withholding tax to zero (other than on participating interest) is the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty. The relevant rate of Canadian withholding tax on interest paid to a non-arm’s-length non-resident who is the beneficial owner of the interest payment will generally be:

- 25% for recipients resident in a country with no Canadian tax treaty;

- 0% for U.S. residents entitled to benefits under the Canada-U.S. tax treaty; and

- 10% or 15% for recipients resident in any other country with a Canadian tax treaty.

Rents and Royalties

“Rents, royalties or similar payments” are addressed in Part XIII in s. 212(1)(d). “Rents” are fairly straightforward. The courts have interpreted the term “rent” as being “inseparable from the connotation of a payment for a term, whether fixed in time or determinable on the happening of an event or in a manner provided for, after which the right of the grantee to the property and to its use reverts to the grantor”, whether or not paid as a lump sum. 8 The Queen v. Saint John Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co. Ltd., 80 DTC 6273 (FCA). Rental payments for the use of (or right to use) outside Canada any tangible property are excluded from tax (s. 212(1)(d)(ix)). A non-resident receiving rent in respect of land in Canada can elect to be taxed under Part I on a net basis rather than under Part XIII on a gross basis (s. 216).

Canada generally does not give up its right in tax treaties to tax rent or other income derived from real property in Canada. In this regard, for equipment or structures it may be necessary to determine as a matter of real property law whether such items have become affixed to and thereby part of the underlying land (“fixtures”) or not.

The taxation of royalties and similar payments under Part XIII is much more challenging, for a variety of reasons:

- s. 212(1)(d) contains a number of express inclusions in the charging provision that go beyond the general meaning of the term “royalty” and are not connected with intellectual property (IP), e.g., payments for certain services, and payments based on use of or production from any property in Canada;

- a number of the specific inclusions in s. 212(1)(d) relating to the use of property must be read together with the exclusions (e.g., 212(1)(d)(x)) in order to accurately establish the scope of the tax;

- because various forms of IP and similar rights (e.g., trademarks, patents, services, copyright) are frequently treated differently, licensing agreements that are not drafted so as to separate the bundle of rights into their constituent parts so that they can be taxed (or not) separately often result in the CRA applying the least favourable withholding tax rate to the entire payment; 9 However, where the CRA fails to allocate a bundled payment between taxable and non-taxable amounts, the courts have determined that no portion of the payment is taxable: see Hasbro Canada Inc. v. The Queen, 98 DTC 2129 (TCC): “ . . . it has been decided that, where a payment can reasonably be considered to be in part for something taxable and in part for something non-taxable, there is an onus on the Minister to specify which portion of the payment is subject to the taxing provision relied upon. If the Minister fails to make this allocation, the taxpayer will not be subject to tax under that particular provision.” See also CRA document 2011-0431871I7, dated December 4, 2012. and

- for recipients in countries with a Canadian tax treaty, establishing whether or not treaty relief is available requires (1) carefully reviewing the scope of relief provided in either the Royalties article of the treaty (if the payment comes within the treaty definition of a “royalty”) or others (if not), and (2) then analysing the complex “back-to-back” and character substitution anti-avoidance regime described below.

It is always appropriate to seek professional advice when dealing with the Part XIII taxation of royalties and similar payments, especially when a tax treaty is involved.

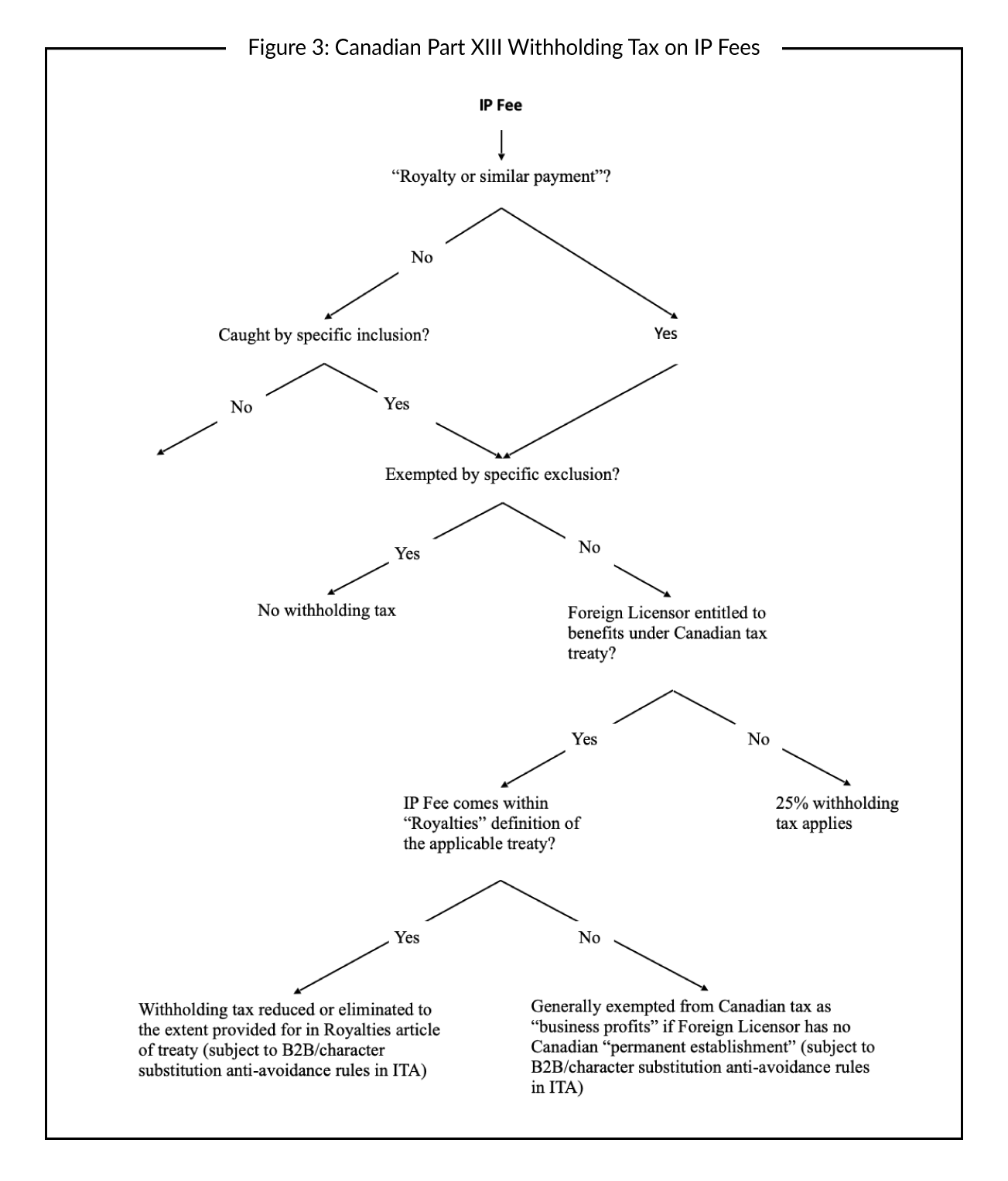

Three questions must be answered to establish whether a particular payment comes within Part XIII under domestic law:

- is the payment a “royalty or similar payment” under general principles;

- do any of the specific inclusions in any of ss. 212(1)(d)(i) – (v) catch the payment; and

- is the payment excluded from tax under the exceptions in any of ss. 212(1)(d)(vi) – (xii).

If the amount is taxable under the ITA and the recipient is resident in a country with a Canadian tax treaty, the recipient should determine whether such treaty reduces or eliminates Canadian tax. Figure 3 illustrates the analytic process. While the process described there seems simple in the abstract, in practice it is much more work to determine whether Part XIII tax applies to a royalty or similar payment and if so at what rate. The domestic law and treaty analysis with reference to the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty is summarized in Table 1.

In the case at bar, the payments were the payee’s profits and were in no way related to the [Canadian payer’s] profits nor were they related to the [Canadian payer’s] gross sales of the units. Whether the [Canadian payer] sold all the units or none of them, whether it made profits or not, did not influence the amount of money paid. There was no element of contingency in the payments in question and an element of contingency is the essence of a royalty payment.

A “royalty” is also not a payment:

- for services (as opposed to for the use of property); 11 E.g., Regulation 105 withholding for services rendered in Canada, discussed above under 2. Regulation 105 Withholding, or a specific inclusion to non-resident withholding for IP in s. 212(1)(d)(iii) described below. See Patricia & Daniel Blais O/A Satronics Satellites v. Her Majesty the Queen, 2010 TCC 361, para. 22. or

- for the purchase (rather than use) of property.

Whether or not a payment is a “royalty or similar payment,” it will be taxed under Part XIII (subject to treaty relief) if it comes within any of ss. 212(1)(d)(i) – (v) and does not fall within the exceptions in ss. 212(1)(d)(vi) – (xii). ss. 212(1)(d)(i) – (v) go far beyond the traditional concept of a “royalty”:

- s. 212(1)(d)(i) in particular applies to payments for the use of or right to use property any property in Canada whether or not the payment is in any way contingent on the payer’s use of or benefit from the property’s use; and

- s. 212(1)(d)(iii) applies to payments for certain services (rather than the use of property) contingent on the payer’s use or benefit (subject to an exclusion for services performed in connection with the sale of property or negotiation of contracts); and

- 212(1)(d)(v) applies to payments that are not for the use of property but which are dependent on (i.e., computed with reference to) the production or use of any property in Canada, including such payments made as the sale price of property. 12 See the discussion of earn-outs below under 14. Sale of Canco.

The third step is to consider the exceptions in ss. 212(1)(d)(vi) – (xii), which narrow the scope of payments that are subject to Part XIII withholding. The primary exceptions are as follows:

- royalties or similar payments on or in respect of a copyright in respect of the production or reproduction of any literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work; 13 S. 2121(1)(d)(vi). See also Syspro Software Ltd. v. The Queen, 2003 DTC 931 (TCC), and CRA documents 2013-0506191E5, dated November 5, 2014; 2012-0441091E5, dated November 23, 2012; and 2004-0086631E5, dated June 14, 2005.

- payments made under a bona-fide research & development cost-sharing agreement; 14 S. 212(1)(viii). See also CRA document 2011-0399581I7, dated November 18, 2013.

- rental payments for the right to use tangible property outside of Canada; and

- payments made to an arm’-s-length person that are deductible in computing the payer’s income for Part I tax purposes from a business the payer carries on outside of Canada.

If a particular payment is caught by s. 212(1)(d) so as to be taxable under Part XIII, a resident of a country with which Canada has a tax treaty must then consider the application of that treaty as a potential source of relief. Canada’s tax treatment of royalty-type and IP-related payments varies meaningfully amongst its tax treaties, and it is important to carefully review the definition of “royalty” in any given treaty to see which article governs.

Table 1: Canadian Non-Resident Withholding Tax on Intangibles

| Type of Payment* | Excluded from Type of Payment | Canada-U.S. Treaty Treatment |

|---|---|---|

| (d)(i): use of or for the right to use in Canada any property, invention, trade-name, patent, trademark, design or model, plan, secret formula, process or other thing whatever (including use of a merchandising concept or technique (Farmparts)) | Payment for exclusive right to buy and resell property, i.e., distributorship (Farmparts; see also CRA document 2017-0701291I7) | “Royalties” include payments for use of or right to use any patent, tangible personal property, trademark, design, model, plan, secret formula or process: Article XII(4) Payments for the use of or right to use patents or computer software not taxable in payer’s country: Article XII(3)(b) and (c)** Payment for exclusive distribution rights not “royalties” within treaty definition, and generally treaty-exempt as business profits:** CRA document 2017-0701291I7 |

| (d)(ii): information concerning industrial, commercial or scientific experience where payment dependent in whole or in part on use, benefit, production, sales or profits (including “know-how”: Hasbro) | Payment for know-how that is skills in trade practices in a particular area of the world or general business acumen in handling day-to-day commercial transaction, or that is used in performing services for but not imparted to the payer (Hasbro) | Payments for the use of or right to use information concerning industrial, commercial or scientific experience not taxable in payer’s country (unless relating to rental or franchise agreement): Article XII(3)(c)** See also CRA document 2012-0457951E5 Article XII(3)(c) extends to royalties paid for the use of or right to use (1) know-how, and (2) designs, models, plans secret formulas or processes: 1995 Technical Explanation |

| (d)(iii): services of industrial, commercial or scientific character where payment dependent in whole or in part on use, benefit, production, sales or profits, excluding services in connection with selling property or negotiating contracts | Payment for services in connection with selling property or negotiating contracts: Hasbro (commissions to buying agents) CRA documents 2013-0495611E5 (warranty sales incentives) and 2002-013082 (training commissions) | Services not included in “royalties” definition: generally treaty-exempt as business profits** See also CRA documents 2011-0416181E5 (fee for per-click online advertising), 2011-0431871I7 (training programs), 2007-0253321E5 (generally) and 2005-0161381I7 (maintenance payments) for further examples of treaty-exempt services payments |

| (d)(iv): payments not to use (or permit use) of property in (d)(i) or information in (d)(ii) | Payments for option to purchase and for purchase price of property: CRA document 2006-0179371I7 | Not included in “royalties” definition: generally treaty-exempt as business profits** See also CRA documents 2017-0701291I7 and 2004-0086631E5 |

| (d)(v): that is dependent on the use of or production from property in Canada | Sale price of property structured as a reverse earn-out or on share sales described in IT-426R: CRA documents 2019-0824461C6 and 2006-0196211C6 | “Royalties” defined to include gains from sale of intangibles if contingent on use or production Payment for use of customer list in Canada treaty-exempt as being for commercial information: CRA document 2013-0494251E5 |

* Excluded from tax are (1) royalties or similar payments relating to a copyright in respect of the production/reproduction of literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work, or (2) payments made under a bona-fide research & development cost-sharing agreement.

** Assuming payment is not connected to a source-country permanent establishment of the recipient.

The Queen v. Farmparts Distributing Ltd., 80 DTC 6157 (FCA)

The Queen v. Saint John Shipbuilding & Dry Dock Co. Ltd., 80 DTC 6272 (FCA)

Hasbro Canada Inc. v. The Queen, 98 DTC 2129 (TCC)

Patricia & Daniel Blais O/A Satronics Satellites v. Her Majesty the Queen, 2010 TCC 361

Grand Toys Ltd. V. MNR, 90 DTC 1059

Part XIII withholding in respect of royalties is supported by a complex anti-avoidance regime discussed below.

Management and Administration Fees

“Management and administration fees or charges” are included within the scope of Part XIII under s. 212(1)(a). The CRA interprets this term as follows: 15 Archived Interpretation Bulletin IT-468.

For the purposes of paragraph 212(1)(a) the Department considers that the term “management or administration” generally includes the functions of planning, direction, control, co-ordination, systems or other functions at a managerial level. These functions may involve services for various departments of a business such as accounting financial, legal, electronic data processing, employee relations, management consultation, labour negotiations, taxation, etc. relating to the management or administration. It is not possible to provide an all-inclusive definition of management fees in an interpretation bulletin, and it is suggested that the above comments be read together with the comments below in order to determine whether an amount paid or credited to a non-resident in a particular set of circumstances constitutes a management fee that is subject to a non-resident tax under paragraph 212(1)(a).

However, in practice the scope of such fees actually subject to Part XIII withholding is much narrower. Specific exclusions exist for

- services performed by a non-resident in the ordinary course of its business, if the non-resident deals at arm’s length with the payer; and

- payment of specific expenses incurred by a non-resident in performing services for the benefit of the payer (s. 212(4)).

This is consistent with the CRA’s “restrictive interpretation” of the term “management or administration fees”, which cites statements by the Minister of Finance at the time s. 212(1)(a) was enacted to the effect that this provision does “not include[e] an amount paid for services to an independent firm and, per subsection 212(4), not including specified amounts paid for identifiable services such as transportation, insurance, advertising, accounting and research.” 16 CRA document 2016-0636721I7, dated March 30, 2017.

Where management and administration services are being provided “in Canada,” the potential application of Regulation 105 must be considered

Some Canadian tax treaties include a specific article dealing with management fees. In most cases however, no specific provision exists with the result that the Business Profits article of the treaty governs. 17 The CRA accepts this result (to the extent of “reasonable” fees) in Information Circular IC77-16R4, para. 15. In such cases Canada will not be allowed to tax a resident of the other country who meets whatever the standard is in that treaty for claiming treaty benefits, unless the non-resident is providing such services through a permanent establishment in Canada.

Other Payments

A variety of other payments beyond those described above are also subject to Part XIII withholding. Perhaps the most important of these to be aware of is s. 212(1)(i), applicable to payments in respect of what are colloquially referred to as “restrictive covenants.” These are payments received in exchange for granting such a “restrictive covenant,” being defined broadly as an agreement or undertaking affecting (or intended to affect) the acquisition or provision of property or services by the recipient or a person related to the recipient (s. 56.4). While the provision is subject to certain exceptions relating to non-competition covenants and similar undertakings made in the context of a sale of property, the wording of this provision is extremely broad and are particularly adverse for non-residents, since they can recharacterize capital gains that are often untaxed in Canada into payment subject to Part XIII withholding. While these rules were originally motivated by payments made for covenants not to compete with buyers, they extend far beyond this simple case and require careful attention where sellers (or non-arm’s-length persons) are providing undertakings or agreements beyond a simple share sale.

18 For an example of how this provision was recently applied to a non-resident seller who received a separate payment from another shareholder for entering into a share purchase agreement with a buyer, see Pangaea One Acquisition Holdings XII S.A.R.L. v. Canada, 2020 FCA 21. CRA document 2014-0539631I7, dated November 20, 2014, illustrates the CRA’s expansive interpretation of this provision. A trust resident in Canada that allocates income out to beneficiaries is generally entitled to deduct such amount from its own income. Such amounts (as well as capital dividends) are subject to Part XIII tax, subject to relief under a tax treaty (s. 212(1)(c)).

Various forms of pension, retirement and employment-related amounts are also subject to Part XIII tax, in particular those made by various forms of tax-exempt entities such as registered retirement savings plans, tax-free savings accounts and deferred profit-sharing plans. Timber royalties in respect of a “timber resource property” or timber limit in Canada are subject to Part XIII tax (212(1)(e)), including amounts paid to harvest timber that are computed with reference to the amount harvested. 19 For an example, see CRA document 2002-0173367, dated July 4, 2003. A non-resident receiving a timber royalty may elect under s. 216 to be taxed on its net income under Part I rather than on a gross basis under Part XIII.

Non-residents are subject to 25% Part XIII tax on amounts paid or credited to them by a Canadian resident in respect of a right in or to the use of (1) a motion picture film or (2) a film, video tape, or other means of reproduction for use in connection television (other than exclusively for news programs produced in Canada). However, the amount on which the tax applies is limited to the extent to which the payment relates to the use or reproduction in Canada. Thus for example, payments to a non-resident digital content provider of movies and TV shows for streaming to Canadian and foreign subscribers by a Canadian company are subject to Part XIII withholding (subject to treaty relief) to the extent of the Canadian payer’s Canadian subscriber base (but not foreign subscribers for viewing outside of Canada). 20 CRA document 2017-0715561E5, dated March 27, 2018. Note that payments for the outright purchase of films ad TV shares (as opposed to a mere right to use or reproduce) are outside the scope of this provision.

A non-resident individual who is an actor (or a corporation related to such a person) is subject to a 23% withholding tax on amounts paid or credited to them (or on their behalf) for the provision in Canada of acting services in a film or video production (s. 212(5.1)). Such person can choose to instead be taxed under Part I on their net income by filing an election to do so (s. 216.1). Further information on the CRA’s administrative policies in this area are available on its website.

Back-to-Back Loan & Character Substitution Rules

The Part XIII withholding tax rules applicable to interest and royalties are supported by a complex regime designed to prevent the reduction of tax via the insertion of a “good” intermediary (i.e., a person entitled to a lower withholding tax rate, either under domestic law or a tax treaty) between the payer of the interest or royalty and the perceived “real” recipient. These rules in effect look behind the actual payment made by the Canadian resident and increase Part XIII tax otherwise owing in various circumstances. They are complicated (even by tax standards), often difficult to work through on the facts, and require professional advice to navigate.

While a detailed discussion of these complex rules is not possible here, it is useful to describe in general terms these rules and the thinking behind them. To begin with, both interest (to the extent compliant with thin capitalization limitations) and royalties are payments that are generally deductible to the payer, making them more attractive as a way for a foreign parent corporation to extract funds from a Canadian subsidiary than some alternatives (e.g., dividends). Moreover, as noted above in the sections dealing with interest and royalties, in many cases these types of payments benefit from reduced or no Part XIII withholding tax:

- interest paid to an arm’s-length creditor is generally exempt from Part XIII withholding;

- interest paid to a non-arm’s length creditor entitled to claim benefits under the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty is treaty-exempt from Part XIII tax;

- a number of exemptions from Part XIII tax exist for royalties, either under the ITA or a bilateral Canadian tax treaty.

In the government’s view, this creates incentives for planning that erodes the Canadian tax base, either by:

- inserting a “good” intermediary entitled to a reduced rate of Canadian withholding tax in between the Canadian payer and the “real” non-resident creditor or licensor; or

- creating a conduit-type structure whereby the payment made by the Canadian to an intermediary takes a tax-advantageous form (i.e., interest or royalty), while a connected payment from the intermediary to the Canadian payer’s “real” counterparty takes a different form (e.g., a dividend from the intermediary to the “real” counterparty).

To this end, Part XIII contains so-called “back-to-back” (B2B) rules 21 Ss. 212(3.1) – (3.94). that may apply if a connection exists between (1) a debt or royalty that Canco owes to a ‘‘good’’ creditor (for example, an unrelated bank in the case of a loan) from a withholding tax perspective; and (2) specific arrangements between that ‘‘good’’ creditor and a non-resident entitled to a worse withholding tax rate than the “good” creditor. For example, if Canco’s foreign parent made a loan to a third party bank which in turn made a loan to Canco, the B2B rules would ignore the third party bank and effectively deem the foreign parent to be Canco’s creditor, causing higher Canadian interest withholding tax (except in the case of a U.S. parent entitled to a 0% interest withholding tax rate under the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty). In very general terms, the kind of connection that must exist between the amount owing by the Canadian payer to the “good” creditor and between the “good” creditor and the non-resident is where either

- the amount owing by the Canadian payer exists “because” of the second amount (or recourse under the second amount is limited to the amount owed by the Canadian payer); or

- the “good” creditor has a “specified right” in respect of property granted by the Canadian payer, which right was required under the terms of the amount the “good” creditor owes to the non-resident.

In the case of royalties, the B2B rules may apply to arrangements where the Canadian licensee pays or credits an amount in respect of a royalty or similar payment to a non-resident (the “immediate licensor”) if the following conditions are met:

- at or after the Canadian licence is entered into, the immediate licensor (or person not dealing at arm’s-length with such licensor) has an obligation to pay an amount to another person (the “ultimate licensor”) under a licence (the “other licence”) that has certain causal connections with the Canadian licence (i.e., similar to those described above with respect to debts);

- had the Canadian licensee paid the ultimate licensor instead of the immediate licensor, greater Canadian royalty tax would have occurred; and

- if the ultimate licensor deals at arm’s-length with the Canadian licensee, one of the main purposes of other licence was to reduce Canadian tax.

In either case, where applicable these rules treat the Canadian as having paid the interest or royalty to the ultimate creditor or licensor, such that withholding tax at the higher rate applies.

A further set of “character substitution” rules 22 Ss. 212(3.6)-(3.7) and (3.92)-(3.93). applies to deem a B2B relationship to exist in certain circumstances where the Canadian payer,

- pays interest to an intermediary that in turn pays a royalty to a non-resident;

- pays a royalty to an intermediary that in turn owes money to a non-resident; or

- pays interest or a royalty to an intermediary shares in which are owned by a non-resident, if certain conditions exist in respect of those shares.

These rules are highly complex and should be considered whenever a treaty reduces Canadian withholding taxes on payments of interest or royalties.

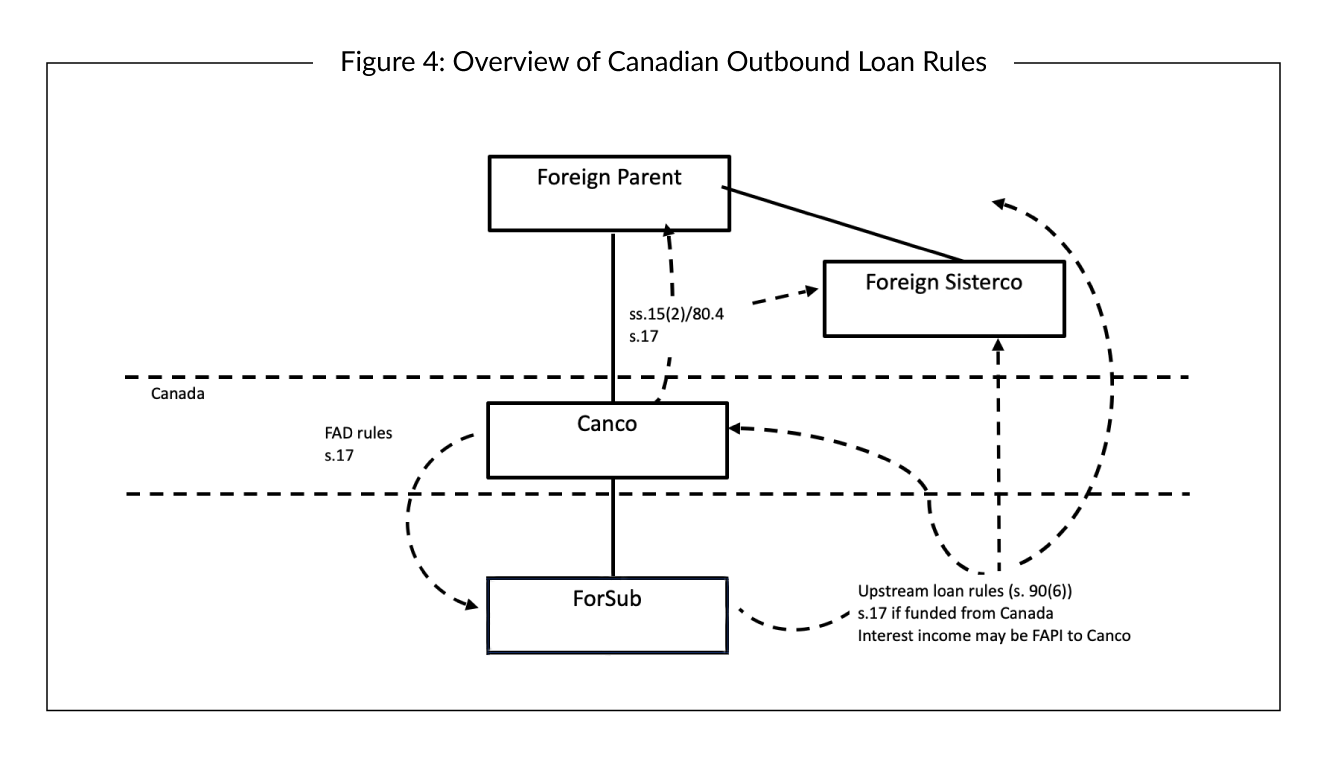

2. Loans

- A variety of complex and often overlapping rules govern the tax impact on Canco of making loans to non-residents of Canada

- In general, these rules either impute an arm’s-length rate of interest to Canco or deem Canco to have paid a dividend to its foreign shareholder

- Conceptually similar rules apply to loans made by a foreign affiliate of Canco to Canco or to non-arm’s length non-residents (“upstream loans”)

The starting point is s. 15(2), which targets debt involving a particular corporation and one of its shareholders. However, the provision is in fact much broader, because the actual creditor need not be that particular corporation, and the actual debtor need not be a shareholder of any corporation. It may apply where (1) the creditor is the particular corporation or another corporation related to it, and (2) the debtor (other than a Canadian-resident corporation) is (or is someone not dealing at arm’s-length with) a shareholder of that particular corporation. 23 The s. 15(2) rules are supported by detailed “back to back” anti-avoidance provisions designed to prevent circumvention via the use of intermediaries. The basic premise of this rule is that such loans are de facto shareholder distributions and should be treated as such and included in the debtor’s income unless falling within certain limited exceptions:

- debt repaid by the end of the creditor’s second taxation year after the debt was incurred (if not part of a series of debts and repayments); 24 For the CRA’s views on what constitutes a series of loans and repayments, see CRA document 2012-0443581E5, dated August 15, 2012.

- debt owing (1) between non-residents of Canada, (2) by certain employees of the creditor, (3) to Canadian residents from their “foreign affiliates”, 25 See fn 35, supra. or (4) arising in the ordinary course of the creditor’s business if repayment arrangements are made promptly; and

- debt which the parties have elected to have s. 17.1 apply to instead (see below).

Where s. 15(2) applies, the debt is simply included in the debtor’s income. If the debtor is a non-resident, the debt is treated as a dividend paid by a Canco to the non-resident, such that dividend withholding tax applies. A subsequent repayment of the debt may entitle the debtor to a corresponding deduction from income (or refund of withholding tax previously paid).

A related provision (s. 80.4(2)) applies to the same range of persons that s. 15(2) applies to, i.e., debts owing by a person (other than a Canadian-resident corporation) who is (or is someone not dealing at arm’s-length with) a shareholder of a particular corporation to a creditor that is either that corporation or a corporation related to it. If the debt was incurred by virtue of the shareholding, this provision deems the debtor to have received a benefit to the extent that interest on that debt during the year computed at a prescribed rate of interest exceeds interest actually paid by the debtor within 30 days from year-end. As such, this rule requires actual payment of an arm’s-length rate of interest to avoid a taxable benefit, which for a non-resident debtor would be deemed to be a dividend subject to withholding tax (ss. 15(9) and (1) and 214(3)(a)). The rule does not apply to the extent s. 15(2) applies to the debt to create an income inclusion or deemed dividend (s. 80.4(3)).

Where a non-resident corporation controls a Canco to which it (or a related a non-resident corporation) owes money and s. 15(2) otherwise applies, they may jointly elect to cause s. 17.1 to apply to the debt instead of s. 15(2). The s. 17.1 rule essentially treats the debt as a “real” loan rather than a disguised dividend, and requires Canco to include no less than a minimum prescribed amount of interest (4.27% for Q3 2020) in its income for the year.

A broader rule in s. 17 applies to a debt owed by any non-resident person to a Canco, also requiring Canco to include no less than a minimum prescribed amount of interest in income. The scope of this provision is extended by an “indirect loan” rule applicable where a non-resident owes money to an intermediary that has in turn made a related loan or transfer of property to a Canco. The s. 17 rule does not apply to:

- debts to which s. 15(2) has applied (to create dividend withholding tax that has not been refunded) or 17.1 has applied;

- debts that are repaid within one year; or

- debts owing by (1) arm’s-length non-residents that are ordinary course trade debts, or (2) controlled foreign affiliates of Canco incurred in respect of their active business.

Finally, s. 90(6) applies where the creditor is a “foreign affiliate” of a Canadian resident (instead of the Canadian resident itself), and the debtor is (or does not deal at arm’s length with) that Canadian resident. As such, s. 90(6) addresses both loans that replace what would otherwise be equity distributions from the foreign affiliate directly to the Canadian resident, and de facto repatriations out from “under” Canada to non-residents “above” the Canadian resident.

This rule includes the amount of the debt in the Canadian resident’s income unless the debt comes within any of a number of exceptions:

- s. 15(2) applies to the debt;

- the debt is repaid within two years (if not part of a series of debts and repayments);

- the debtor is a controlled foreign affiliate of the Canadian resident; or

- the debt arose in the ordinary course of the creditor’s business if bona fide repayment arrangements are made within a reasonable time.

Moreover, to reflect the fact that Canada’s foreign affiliate rules allow a Canadian corporation to receive dividends from a foreign affiliate effectively free of Canadian tax to the extent attributable to the affiliate’s active business income, a Canco that suffers a s. 90(6) income inclusion may claim an offsetting reserve to the extent that it could have received the amount directly as a foreign affiliate dividend without incurring Canadian tax. The reserve is added back to the Canco’s income the following year, with a new reserve claimable for that year if sufficient favourable tax attributes remain unused and available that would allow a tax-free foreign affiliate dividend.

The upstream loan regime is also supported by a back-to-back anti-avoidance rule (s. 90(7)). Note that under anti-deferral elements of the Canadian foreign affiliate regime, passive income earned by a controlled foreign affiliate of a Canadian taxpayer is often imputed back to (and taxed in the hands of) the Canadian taxpayer. Thus, where a controlled foreign affiliate of a Canadian taxpayer makes a loan, one of the issues to consider is whether any interest income the controlled foreign affiliate earns will be imputed back to the Canadian taxpayer.

Table 2. Amounts Owing by Non-Residents to Cancos (and Their Foreign Affiliates)

|

Creditor |

Debtor |

Principal Exceptions |

Consequence |

Other |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s. 15(2) | Corporation | Person (other than a Canco) that is (or is connected to) a shareholder of either Creditor or a corporation related to Creditor | – Debt repaid before Creditor’s second taxation year-end – Debt to which s. 17.1 applies – Debt between non-residents – Debt owing by employees – Debt owing from foreign subsidiaries – Debt arising in ordinary course of Creditor’s business |

– Amount of debt included in Debtor’s income; if Debtor is non-resident, amount is deemed to be a dividend paid by Canco to Debtor, triggering dividend withholding tax; reversed upon debt repayment | Regime supported by back-to-back debt anti-avoidance rules s.80.4 interest benefit rule |

| s. 17.1 | Canadian-resident corporation controlled by a non-resident corporation | Non-resident corporation that controls Creditor (or that deals non- arm’s length with non-resident corporation that controls Creditor) | Elective regime that applies only where both (1) either 15(2) or the FAD rules* would otherwise apply, and, (2) the parties jointly elect into s. 17.1 regime instead | Creditor required to include at least a minimum prescribed amount of interest in income | Not available if tax treaty reduces impact of application |

| s. 17 | Canadian-resident corporation | Non-resident person |

– Debt repaid within 1 year |

Creditor required to include no less than a minimum prescribed amount of interest in income | Regime supported by back-to-back and indirect loan anti-avoidance rules |

| s. 90(6) | Foreign affiliate** of a Canadian resident | The Canadian resident or any person not dealing at arm’s length with the Canadian resident (except certain closely-held foreign subsidiaries) |

– Debt repaid within 2 years |

Amount of debt included in Canadian resident’s income, less elective reserve for amounts that could have been paid to Canadian resident as tax-free dividend. Deduction from income permitted on repayment of debt | Regime supported by back-to-back anti-avoidance rule |

* See Canadian Subsidiaries page, section 6. Foreign Affiliate Dumping (FAD) Rules.

** A non-Canadian corporation in which the relevant Canadian has at least a 10% direct or indirect equity interest.

Cash pooling arrangements are a frequent source of problems for MNEs with Canadian members. There are no Canadian tax rules designed to accommodate cash pooling arrangements, either physical (cash is actually swept from accounts in each country daily) or notional (the external group lender notionally nets positive and negative balances in each country, but doesn’t actually move cash to net them out). As a result, cash pooling arrangements are governed by the general rules described above for debts owing to Canadians by non-residents (see above) and vice versa (e.g., thin capitalization).

The results are often quite undesirable. 26 See for example Mark Brender, Marc Richardson Arnould and Patrick Marley, “Cross-Border Cash-Pooling Arrangements Involving Canadian Subsidiaries: A Technical Minefield”, (Bloomberg BNA) Tax Management International Journal, June 13, 2014, p. 345. The CRA has stated that it has no discretion to not apply s. 15(2) or other provisions that technically apply to cash pooling arrangements, and in general has not adopted accommodating administrative policies facilitating their use: see CRA documents 2017-0692631I7, dated February 27, 2018, and 2015-0595621C6F, dated October 9, 2015. The CBA-CPA Canada Joint Committee on Taxation raised several issues with the application of the B2B rules to notional cash pooling arrangements with Canadian participants, even when undertaken entirely for commercial reasons. 27 See CBA-CPA Canada Joint Committee on Taxation submission to Department of Finance dated July 25, 2016, pages 10-11. CRA document 2015-0614241C6, dated November 17, 2015, stated that “deposit balances of the non-resident pool participants would be considered ‘intermediary debts’ for the purposes of [the B2B rules], with the result that the back-to-back loan rules would be engaged” if their other preconditions were met. MNEs that involve their Canadian affiliates in cross-border cash pooling should obtain advice as to the potential Canadian tax consequences.

3. Repatriation from Canadian Subsidiaries

- when repatriating funds from a Canadian subsidiary, there are a variety of Canadian tax issues to consider.

- these include withholding tax, deductibility, and impact on thin capitalization.

- cash pooling is an area of frequent concern for MNEs with Canadian group members, as there are no specific rules designed to accommodate them.

- whether the payment is deductible to Canco;

- whether withholding tax is applicable to the payment;

- transfer pricing constraints on the payment;

- the impact of the payment on the application of the thin capitalization rules to Canco, which determine how much interest-deductible debt Canco can borrow from non-arm’s-length non-residents; and

- if borrowed money is used to fund the payment, whether or not interest on that borrowing will be deductible under general principles.

Table 3 summarizes these issues for the typical repatriation alternatives.

Table 3. Summary of Repatriation Options from Canada

|

Withholding Tax |

Deductible to Canco |

Effect of Canco Thin Capitalization |

Other |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dividend | 25%: treaty-reduced as low as 5% | No | Retained equity decrease reduces equity in following year | Corporate law limits on payment; consider interest deductibility if paid using borrowed money |

| PUC Return | None, to the extent of Canco PUC | No | PUC decrease reduces equity in current year | Corporate law limits on payment; consider interest deductibility if paid using borrowed money; no U.S.-style E&P rule |

| Interest | 25%: treaty-reduced as low as 10% (0% for qualifying U.S. residents); supported by B2B anti-avoidance rule | Yes, subject to thin cap rules | Retained equity decrease reduces equity in following year | Deductibility requires debt be incurred for income-earning purpose; transfer pricing and deductibility issue if rate exceeds arm’s-length rate; |

| Loan | None if repaid within permissible time limit and Canco is paid enough interest (s. 15(2))/80.4) or joint election into s. 17.1 regime | No | None | Transfer pricing or benefit issue if interest too low; variety of base erosion rules potentially applicable; consider interest deductibility if paid using borrowed money |

| Management Fee | 25%: often treaty-exempt if provider has no Canadian permanent establishment | Yes | Retained equity decrease reduces equity in following year | Transfer pricing and deductibility issues if in excess of arm’s-length standard; Reg. 105 withholding if services rendered in Canada |

| Royalty | 25%, subject to some exceptions provided under domestic law and within specific tax treaties; supported by B2B anti-avoidance rule | Yes | Retained equity decrease reduces equity in following year | Transfer pricing and deductibility issues if in excess of arm’s-length standard |

4. Regulation 105 Withholding

- Regulation 105 creates a 15% withholding and notification obligation on a person (Canadian or non-resident) paying an amount to a non-resident of Canada (other than to the payer’s employee) in respect of services rendered in Canada.

- Unlike Part XIII withholding, Regulation 105 withholding is not a final tax; rather, it is a collection mechanism relating to payments to non-residents that may be refunded if the recipient is not otherwise taxable in Canada on the payment.

- Whether or not the recipient is ultimately subject to Canadian tax on the payment does not affect whether Regulation 105 withholding applies, although a waiver relieving the payer from the obligation can be obtained in some circumstances.

- The payer of an amount to which Regulation 105 applies is obligated to withhold and remit to the CRA the amount of the tax owing, failing which the payer is liable for such amount (and potentially interest and penalties), with no time limit for the CRA to re-assess.

- For services rendered in Quebec, a separate 9% withholding obligation exists under Quebec provincial income tax law.

- A variety of traps and anomalies exist within the Regulation 105 regime.

General Principles

A requirement to withhold under Regulation 105 applies whenever a person (Canadian or non-resident) pays a fee, commission, or other amount to a non-resident “in respect of” services rendered in Canada. It does not apply to payments to the payer’s employees (the general employer withholding and remittance regime for payments to employees applies in those circumstances). It also does not apply to the reimbursement of expenses actually incurred by the recipient, because such reimbursements are not “fees, commissions or other amounts in respect of services rendered in Canada” (Weyerhaeuser Co. Ltd. v. The Queen (2006 TCC 65)).

A payer to whom Regulation 105 applies must withhold 15% of the gross amount of the payment and remit that amount to the CRA. The withheld amount is credited towards the non-resident’s Canadian income tax liability (if any). If the Regulation 105 remittance exceeds the non-resident’s actual Canadian income tax liability as ultimately determined (for example, if the non-resident is treaty-exempt on the payment), the non-resident can claim a refund by filing a Canadian income tax return (as discussed below, under some circumstances the CRA will issue a waiver relieving the payer of its withholding obligation). If the payer does not withhold and remit as required, it is liable for the 15% amount, plus interest and penalties, with no time limit for re-assessment.

Regulation 105 withholding is very broad for a number of reasons, most importantly:

- it applies to both Canadian and non-resident payers; 28 Footnote here.

- the obligation to withhold and remit does not depend on whether or not the recipient is otherwise taxable in Canada on the payment, whether by virtue of a tax treaty or otherwise (indeed, the very purpose of Regulation 105 withholding is to give the CRA an opportunity to make this determination while funds are still within Canada);

- the recipient of the payment need not be the entity rendering the “services rendered in Canada;” and

- the payer need not be the entity receiving the “services rendered in Canada.”

Thus, the scope of Regulation 105 goes well beyond the simple payment by a Canadian to a non-resident for services the non-resident is to render to the Canadian payer in Canada.

An example of the type of trap Regulation 105 creates for the unwary is the common situation of customers of an MNE contracting directly with the foreign MNE parent for services that include some element of “in Canada” services, to be provided by the foreign parent’s Canadian subsidiary (i.e. under a separate services agreement between the foreign parent and Canadian subsidiary). Regulation 105 applies to the customer’s payment to the foreign parent, because some portion of that payment is “in respect of” services to be rendered in Canada (in this case by the recipient’s Canadian subsidiary that is fully taxable in Canada on any payment it receives from the foreign MNE parent). In this sense Regulation 105 can create a windfall for the CRA, generating far more tax than would apply if the customer had just paid the Canadian subsidiary directly for the “in Canada” services.

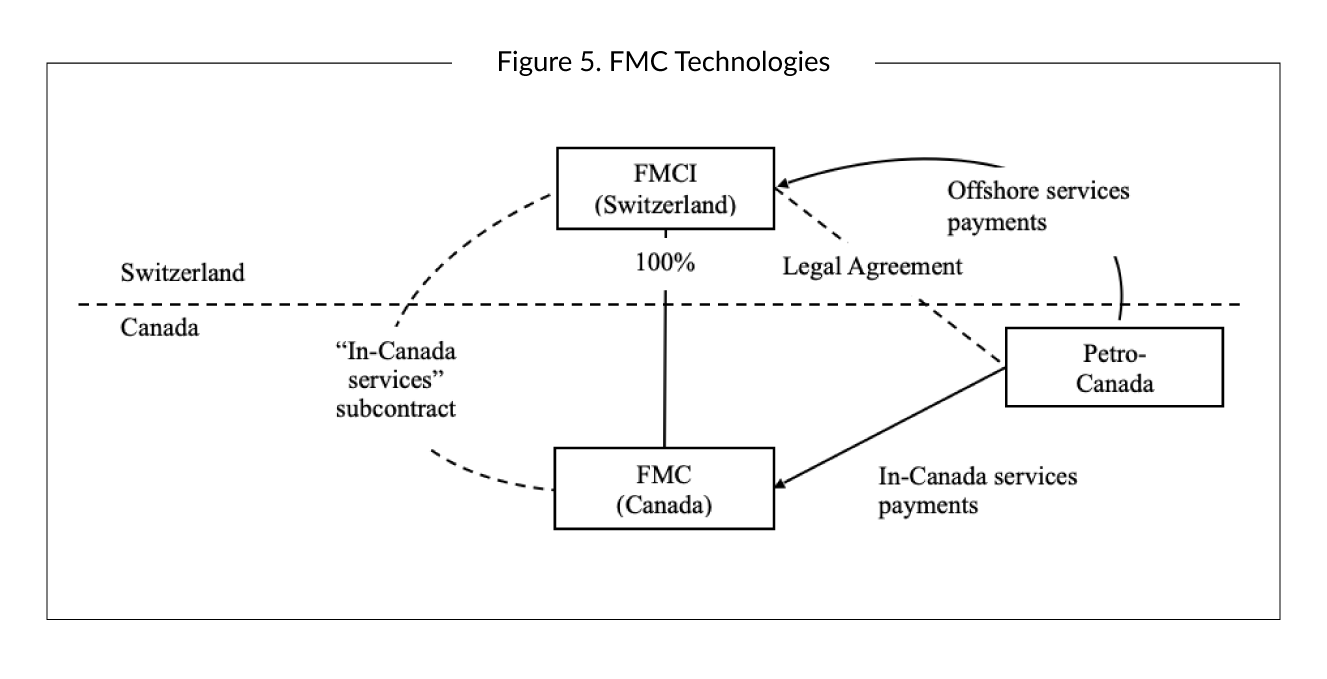

This situation is illustrated by FMC Technologies Company v. The Queen, (2009 FCA 217, aff’g 2008 FC 871), the facts of which are illustrated in Figure 5 below. The key factual elements of this case are as follows:

- the customer (Petro-Canada) had a services contract with the foreign parent (FMCI) a multinational group;

- the Canadian member of the MNE (FMC) was the entity actually providing the “in Canada” services, under a subcontracting agreement between FMCI and FMC; and

- FMC invoiced the customer directly for the “in Canada” services (and FMCI assigned to FMC its rights to be paid those amounts). However, the only party with a legal right to payment for the “in Canada” services from the customer was FMCI.

The CRA assessed Petro-Canada for 15% of the Cdn.$18.8 million invoiced to it by FMC (plus interest and penalties) on the basis that Petro-Canada was required to withhold under Regulation 105, because the legal payee for those amounts (i.e., the entity with a legal claim against Petro-Canada) was FMCI, a non-resident. Even though the payments were made for work actually performed by a Canadian resident (FMC) that had been taxed in Canada on them as a Canadian resident, the CRA held that Regulation 105 applied. This was because FMCI was the only party with whom Petro-Canada had an agreement to provide services, meaning that the payments made by Petro-Canada for the in-Canada services were constructively made to FMCI, even if received by FMC on FMCI’s direction. Petro-Canada (presumably indemnified by its counterparty FMCI) did not challenge the assessments in court. FMCI appears not to have filed Canadian income tax returns, with the result that it could not claim a refund. Finally, the courts denied FMC the ability to recover the withheld amounts, even though they resulted in a windfall for the CRA, because it was neither the taxpayer assessed nor the legal payee (having no direct legal rights against the customer). The case is a cautionary tale of how aggressively the CRA administers Regulation 105, and how unexpected Regulation 105 obligations may be created in situations beyond the simplest case of the recipient rendering services directly for the payer.

Non-residents often seek to relieve their Canadian customers of the burden of effecting Regulation 105 withholding. To do so, a Canadian subsidiary of the MNE may provide all “in Canada” services under a direct contract between the subsidiary and the customer, with fees for such “in Canada” services being calculated separately and billed by (and paid directly to) the Canadian subsidiary. 29 Unless the “in Canada” portion of payments to a non-resident is clearly identifiable, the CRA will typically assess Regulation 105 withholding on the entire amount paid to a non-resident for services. Since the recipient of such payments is a Canadian resident, no Regulation 105 withholding obligation will apply to the customer. Any “outside of Canada” services (which are not subject to Regulation 105 withholding) can be contracted for directly by non-Canadian MNE group members. Regulation 105 withholding will not apply to these payments either, since such payments are not in respect of services rendered “in Canada.”

An essentially similar result may be achieved without the customer directly paying the MNE’s Canadian subsidiary, if necessary. When a non-resident engages a subcontractor (related or unrelated) to provide services in Canada to the non-resident’s customer, the non-resident can pay the subcontractor directly and present the subcontractor’s invoice to the customer as a cost of the non-resident to be reimbursed. The CRA accepts (in reliance on the Weyerhauser decision) that the customer’s payment of such a separately identified expense of the non-resident is not a “fee, commission or similar amount” described in Regulation 105 but rather an expense reimbursement.30 See CRA document 2008-0297161E5, dated September 16, 2009.

It is not uncommon for a non-resident entity to “second” an employee to its Canadian affiliate, whereby the Canadian entity becomes the seconded employee’s employer for a temporary period. The CRA takes the position that the non-resident will not thereby be considered to be rendering services in Canada for purposes of Regulation 105 or carrying on business in Canada, in cases where the non-resident is reimbursed at cost for the employee’s services and no mark-up is charged. 31 See CRA document 2014-0542411R3, 2015. The CRA accepts an administrative overhead charge of $250/month per employee to be acceptable, where for administrative purposes the seconded employee remains on the non-resident’s payroll system and the

Administration and Waiver

The key administrative elements of Part XIII tax are as follows:

- a payer who fails to deduct or withhold as required is itself liable for the non-resident’s Part XIII tax owing, and is entitled to deduct or withhold from any amount payable to the non-resident (or otherwise recover) any Part XIII tax it pays on the non-resident’s behalf (s. 227(8.4)). A comparable rule applies to amounts deducted or withheld by the payer but not remitted to the CRA as required (s. 227(9.4));

- an amount to be withheld under Regulation 105 must be remitted to the CRA by no later than the 15th day of the following month (Regulation 108);

- a person who fails to deduct and withhold an amount as required is liable to a penalty of 10% of the amount, or 20% if the failure is attributable to gross negligence and the same payer has already been penalized for a previous failure in the same calendar year (s. 227(8)). In such circumstances, interest on the amount that should have been deducted begins to run on the 15th day of the month following the in which the deduction or withholding should have been made (s. 227(8.3));

- similarly, a person who has deducted or withheld an amount but has failed to remit it as required is liable to a penalty of up to 10% of the amount, or 20% if the failure is attributable to gross negligence and the same payer has already been penalized for a previous failure in the same calendar year (s. 227(9)). In such circumstances, interest on the amount that should have been deducted begins to run on the day the deduction or withholding should have been made (s. 227(9.2)).

- no legal action may be taken against any person for deducting or withholding in compliance (or intended compliance) with their ITA obligations (s. 227(1)), and any agreement not to withhold as required under the ITA is void (s. 227(12));

- payments by an agent of the debtor or to an agent of the recipient carry the deduction and withholding obligation otherwise imposed on the debtor (ss. 215(2) and (3)); and

- there is no time limit on the CRA’s right to re-assess a person for amounts owing under Regulation 105, including interest and penalties (ss. 227(10) and (10.1)).

The CRA webpage on Part XIII tax provides information on various topics, including notification and filing requirement (NR4 information slips and returns).

The primary source of CRA administrative guidance for Regulation 105 compliance is Guide RC4445. This publication is primarily focused on the administrative aspects of Regulation 105 compliance, being the remittance of amounts owing, reporting obligations, and the consequences of non-compliance (e.g., penalties and interest).

An older (but more detailed) source of CRA guidance is Information Circular IC75-6R2. This publication addresses situations such as employee secondments, sub-contracting, and bundled or “multi-tiered” contracts, as well as the interaction between Regulation 105 withholding and instalment payments in respect of Part I tax owing by non-residents.

A waiver procedure for obtaining relief from the CRA for Regulation 105 withholding exists (although in practice it is often not a practical option for obtaining timely relief). Waiver applications may be made on the basis that the non-resident is exempt from Canadian taxation under a relevant tax treaty (“treaty-based waivers”) or because the non-resident is not taxable in Canada under domestic law on the payment (“income and expense waivers”). A separate simplified waiver system exists for persons in the film and television industry.

The waiver application form is R105, which has an accompanying guide. The process for obtaining a treaty-based waiver is explained on the CRA website, which requires the application to be made no less than 30 days prior to the first payment in respect of which relief is sought.