Tax Treaties

Table of Contents

Non-residents of Canada earning Canadian-source income should always consider not only the ITA when seeking to minimize their Canadian tax owing, but also any potentially applicable tax treaty between Canada and another relevant country. Tax treaties reduce tax payable for residents of one country earning income from the other treaty country, and so constitute an important element in cross-border tax planning. This page describes the following:

- how Canada’s tax treaties operate generally;

- the manner in which Canadian courts interpret Canada’s tax treaties;

- the requirements for a non-resident to claim the benefit of tax treaty provisions; and

- special features of the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty.

1. Canada’s Tax Treaties

- Tax treaties between two countries seek to avoid double taxation that may otherwise occur when a resident of one country (the “residence country”) earns income in or from the other country (the “source country”). This occurs by reducing the source country’s right to tax income earned by a resident of the residence country.

- The other principal function of a tax treaty is to provide a dispute resolution mechanism for taxpayers to invoke when they believe that double taxation contrary to the intent of the treaty is occurring.

- Tax treaties over-ride the Canadian tax result that would otherwise occur under the ITA.

- Canada has over 90 bilateral tax treaties, and another 25 tax information exchange agreements with low-tax countries.

- The Multilateral Instrument (MLI) ratified by Canada in 2019 makes various amendments to the text of most of Canada’s tax treaties, the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty being the principal exception.

Role of Tax Treaties

A tax treaty is an agreement between two countries entered into in order to reduce the likelihood that each country will tax the same income without regard to the other, resulting in excessively high taxation (often referred to as “double taxation”). In general terms, tax treaties are directed at situations in which a resident of one country (the “residence country”) earns income in or from the other country (the “source country”). Absent relief provided by a tax treaty, in most cases the residence country would levy tax on the basis that the recipient was a resident of that country, while the source country would tax the same income on the basis that it was earned in the source country. Tax treaties reduce the risk of such “double taxation” by restricting or eliminating the source country’s right to tax in the circumstances and on the terms set out in the tax treaty.

While Canada’s tax treaties generally follow a more or less standard format, the precise terms of any particular tax treaty are based on what the two countries have negotiated between themselves. It is therefore important to review the actual provisions of each relevant tax treaty when determining the impact to a resident of a particular country earning income in another country. Table 1 summarizes the usual or typical impact of a Canadian tax treaty on Canada’s right to tax Canadian-source income earned by a resident of the other treaty country.

Table 1: Typical Impact of Canadian Tax Treaties on Canadian-Source Income

| Type of Income |

ITA Treatment for Non-Resident |

Typical Tax Treaty Treatment |

|---|---|---|

|

Income from Land in Canada |

Taxable under Part I (if carrying on business in Canada) or Part XIII (otherwise) |

No change |

|

Business Income |

Taxable under Part I if carrying on business in Canada |

Only taxable if carrying on business in Canada through a Canadian permanent establishment |

|

Employment Income |

Taxable under Part I if employed “in Canada” |

Exemption if recipient present in Canada for <183 days and remuneration not paid/borne by Canadian resident or permanent establishment |

|

Interest Income* |

25% withholding tax under Part XIII, if non-arm’s-length debtor or if interest is “participating” |

Generally reduced to 10% or 15% (0% for qualifying U.S. residents) |

|

Dividend Income* |

25% withholding tax under Part XIII |

Generally reduced to 15% with further reduction to 5% if ownership threshold met |

|

Royalty Income* |

25% withholding tax under Part XIII |

Generally reduced to 10% with some items reduced to 0% (e.g., copyright royalties) |

|

Capital Gains |

Taxable under Part I if from disposition of taxable Canadian property |

Wide variation, from no change to tax limited to dispositions of land in Canada and interests in equity securities deriving their value primarily from such land (with additional exemptions) |

* Other than such income earned through a permanent establishment in Canada.

The impact of tax treaties on Canada’s right to tax Canadian-source capital gains is particularly diverse, with a wide variation amongst different Canadian tax treaties based on the negotiations between the two countries in question (for a summary of these variations see here.

-

other forms of income (e.g., pensions, income from international shipping, etc.) or particular taxpayers (artists and athletes, tax-exempt organizations, students, etc.);

-

addressing situations whereby both countries claim a particular person is a resident of that country (“dual residency”), such that both countries assert the right to tax the person on their world-wide income on the basis of residency. Some treaties contain a “tie-breaker” rule that determines the basis on which the person will (for treaty purposes) be considered a resident of one country but not the other, while other treaties merely require the respective tax authorities to try and achieve such a resolution.

-

requiring each country to (1) offer additional mechanisms for relieving double taxation (e.g., foreign tax credits reducing local taxes by the amount of foreign taxes paid), and (2) refrain from imposing on nationals 1 “Nationals” (a term defined in the tax treaty) is a concept distinct from “residents.” of the other country taxation that is more burdensome than that to which the first country’s own nationals are subject (i.e., non-discrimination);

-

providing a “mutual agreement procedure” (MAP), whereby a person believing themselves to be subject to double tax contrary to the tax treaty can invoke a process for the tax authorities of the two countries to resolve the issue between them, separate and apart from the normal remedies he/she may have (such as an appeal to the courts); and

-

setting out procedures for the exchange of taxpayer information (and in some cases assistance in collecting taxes owing).

Canada has tax treaties with over 90 countries, constituting an extensive network of bilateral tax agreements. These tax agreements can be found on the Department of Finance website. While Canada’s provinces are not themselves signatories to these tax treaties, the results of these tax treaties are effectively incorporated into provincial income tax by virtue of provincial legislation.

Canada also has tax information exchange agreements (TIEAs) with another 25 countries, along with others currently under negotiation. TIEAs are agreements between Canada and other countries that typically do not impose significant amounts of tax, making the risk of double taxation remote. They do serve however to promote transparency by allowing Canada to obtain tax-related information that assists the CRA in administering the ITA as regards residents of the other country. Canada encourages other countries to sign TIEAs with it by offering preferable tax treatment in its rules dealing with foreign corporations in which Canadian residents own shares (directly or indirectly), comparable to the treatment afforded in those rules to foreign corporations that are resident in countries with which Canada has a full tax treaty. The countries with which Canada has TIEAs are listed on the Department of Finance website.

In some cases the tax authorities of two countries that have entered into a tax treaty will come to agreement on specific issues regarding the interpretation or administration of that treaty. The CRA website lists such competent authority agreements.

The Multilateral Instrument (MLI)

The Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (the “MLI”) effects significant changes to the provisions of most of Canada’s tax treaties. The MLI was conceived as a way of effecting agreed-upon changes to a large number of bilateral tax treaties as to agreed-upon subject matter, without requiring each such tax treaty to be amended separately. Essentially, each signatory to the MLI identifies those specific treaties that it wishes to have amended by the MLI (“covered tax agreements”), and identifies which specific MLI provisions it wishes to apply to each such covered tax agreement. To the extent that both signatories to a particular tax treaty agree as to selected provisions, the MLI (once ratified by each country) is deemed to amend that tax treaty accordingly. An online matching database has been prepared by the OECD to show which treaty counterparties each country has identified as wishing to apply the MLI to and which MLI provisions such country wishes to have apply to that treaty.

The MLI entered into force in Canada December 1, 2019. 2 See Department of Finance release “Canada Ratifies the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting,” August 29, 2019. Canada has designated 84 tax treaties as covered tax agreements. 3 See “Status of List of Reservations and Notifications upon Deposit of the Instrument of Ratification,”. For each such covered tax agreement, if the treaty counterparty has also (1) designated its tax treaty with Canada as a covered tax agreement, and (2) deposited instruments of ratification with the OECD (which brings the MLI into force in that country on the first day of the month following a period of three calendar months from such deposit), the MLI’s provisions will apply:

- with respect to taxes withheld at source on amounts paid or credited to non-residents, on the first day of the following calendar year (i.e., as early as January 1, 2020 for a Canadian tax treaty, if the MLI was in force in the other country before the end of 2019); and

- for all other matters (including taxation of capital gains), for taxation years beginning 6 months after the date which the MLI came into force in the later of the two countries (i.e., as early as taxation years beginning June 1, 2020 for Canadian tax treaties).

Amongst the Canadian tax treaties that the MLI had entered into force in respect of as of the end of 2020 were Canada’s tax treaties with Luxembourg, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Ireland and Singapore, with others following as more countries ratify the MLI. The most significant Canadian tax treaties not impacted by the MLI are Canada’s tax treaties with the U.S. (which is not a signatory to the MLI) and with Germany and Switzerland (both of which are currently under renegotiation).

Canada’s position on the MLI has been to adopt the following amendments to its covered tax agreements:

- Minimum standards on treaty abuse: statement of purpose (Article 6) and principal purpose test (PPT) and/or limitation on benefits (LOB) test (Article 7);

- minimum standards on dispute resolution (Article 16);

- 365-day holding requirement for reduced dividend withholding (Article 8);

- 365-day looking back rule re capital gains and real property (Article 9);

- mandatory binding arbitration (Article 19); and

- resolution of dual residence (Article 4).

The OECD has prepared an Explanatory Statement providing additional guidance on the interpretation of the MLI’s provisions.

The statement of purpose in Article 6(1) as amended in the manner agreed to by Canada adds a reference to the purpose of tax treaties to eliminate double taxation without creating unintended non-taxation or reduced taxation. Revised Article 6(1) reads as follows:

Intending to eliminate double taxation with respect to the taxes covered by this agreement without creating opportunities for non-taxation or reduced taxation through tax evasion or avoidance (including through treaty-shopping arrangements aimed at obtaining reliefs provided in this agreement for the indirect benefit of residents of third jurisdictions).

It remains to be seen whether this additional text will affect the way in which courts will interpret Canada’s tax treaties. The PPT restricting taxpayers’ ability to claim treaty benefits is discussed below in 3. Claiming Treaty Benefits. Further context on Canada’s thinking on the MLI has provided by a senior Department of Finance official (Stephanie Smith) directly involved in Canada’s MLI participation, both at the Canadian Tax Foundation 2019 Annual Conference 4 Penny Woolford, Jonathan Schwarz, and Stephanie Smith, “Implementation of the Principal-Purpose Test as Part of the Multilateral Instrument: Canadian and Foreign Perspectives,” in Report of Proceedings of the Seventy-First Tax Conference, 2019 Conference Report (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 2019), 28: 1-17.” and at the 2019 meeting of the Canadian Branch of the International Fiscal Association. 5 https://taxinterpretations.com/

2. Treaty Interpretation in Canada

- Canadian courts generally interpret tax treaties liberally, and with a view to reducing source-country tax in a manner which conforms with the intent of the two countries who have signed the particular treaty in question.

- The Income Tax Conventions Interpretation Act sets out rules for how Canada will interpret the tax treaties it has signed.

- The OECD Model Income Tax Convention and associated Commentary are sometimes used by Canadian courts as interpretive aids in applying Canada’s tax treaties, although they are no authoritative and the relevance in any particular case depends on the facts.

- Canadian courts have considered other extrinsic aids such as the United Nations Model Double Taxation Convention, United States Model Tax Convention and similar resources in appropriate circumstances.

Because tax treaties exert such a powerful influence on how Canada taxes non-residents (or at least non-residents who are resident in a country with which Canada has a tax treaty), it is essential to understand how Canadian courts interpret and apply them.

In Canada v. Crown Forest Industries Limited et al., 6 95 DTC 5389 (SCC). the Supreme Court of Canada was called upon to interpret the 1980 version of the tax treaty between Canada and the United States. In so doing, the Court stated as follows (at 5393):

In interpreting a treaty, the paramount goal is to find the meaning of the words in question. This process involves looking to the language used and the intentions of the parties.

. . .

Reviewing the intentions of the drafters of a taxation convention is a very important element in delineating the scope of the application of that treaty. As noted by Addy, J. in J.N. Gladden Estate v. The Queen, [1985] 1 C.T.C. 163 (F.C.T.D.), at pp. 166-67:

Contrary to an ordinary taxing statute a tax treaty or convention must be given a liberal interpretation with a view to implementing the true intentions of the parties. A literal or legalistic interpretation must be avoided when the basic object of the treaty might be defeated or frustrated in so far as the particular item under consideration is concerned.

Thus, Canadian courts will go beyond a literal interpretation of the words of a treaty and seek to discern the intentions of the two countries that are party to it, for the purpose of applying the treaty in a manner consistent with those intentions. This is consistent with Articles 31 and 32 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which Canadian tax courts have cited and applied when interpreting tax treaties: 7 See for example Coblentz v. The Queen, 96 DTC 6531 (FCA).

Article 31

1. A treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose.

2. The context for the purpose of the interpretation of a treaty shall comprise, in addition to the text, including its preamble and annexes:

(a) any agreement relating to the treaty which was made between all the parties in connection with the conclusion of the treaty;

(b) any instrument which was made by one or more parties in connection with the conclusion of the treaty and accepted by the other parties as an instrument related to the treaty.

3. There shall be taken into account, together with the context:

(a) any subsequent agreement between the parties regarding the interpretation of the treaty or the application of its provisions;

(b) any subsequent practice in the application of the treaty which establishes the agreement of the parties regarding its interpretation;

(c) any relevant rules of international law applicable in the relations between the parties.

Article 32

Recourse may be had to supplementary means of interpretation, including the preparatory work of the treaty and the circumstances of its conclusion, in order to confirm the meaning resulting from the application of Article 31, or to determine the meaning when the interpretation according to Article 31:

(a) leaves the meaning ambiguous or obscure; or

(b) leads to a result which is manifestly absurd or unreasonable.

Income Tax Conventions Interpretation Act

While tax treaties represent an agreement between two sovereign states, as a practical matter a taxpayer seeking relief under a tax treaty must generally satisfy the country whose taxes are being reduced or eliminated that the treaty in fact applies to that taxpayer’s situation. Put differently, the country whose interpretation of the treaty matters in any particular instance is the country whose right to tax is being constrained. There is no guarantee that both countries will necessarily interpret the text of the tax treaty between them in the same way.

Canada has set out the principles that it applies in interpreting its bilateral tax treaties in the Income Tax Conventions Interpretation Act. The Canadian legislation implementing tax treaties (including the MLI) provides that the ITCIA takes precedence over the terms of the tax treaty or any other law, making the ITCIA a very important source of interpretational guidance in situations where taxpayers are relying on a tax treaty to reduce Canadian taxes.

The following principles are amongst the most important found in the ITCIA:

- a term not defined (or fully defined) in a tax treaty has the meaning it has for ITA purposes from time to time (as opposed to the meaning it had at the date the treaty was entered into);

- the GAAR in s. 245 ITA applies to any benefit provided under a tax treaty; and

- income, gain or loss arising from the disposition of “taxable Canadian property” is deemed to arise in Canada except where the sourcing rules of the tax treaty expressly provide otherwise.

The ITCIA also provides definitions for a number of important terms frequently found in Canada’s tax treaties (e.g., “immoveable property” and “real property”).

OECD Model Treaty and Commentary

The OECD has prepared a Model Income Tax Convention (“OCD Model Treaty”) along with accompanying commentary (the “OECD Commentary”). The OECD Model Treaty serves as a framework for countries to use in negotiating bilateral income tax treaties. Canada uses this framework in negotiating its tax treaties, although it does depart from the OECD Model Treaty in certain respects and of course each treaty is based on the specific items agreed to by the two countries in question. It is therefore important to note that the OECD Model Treaty will not be identical to any particular Canadian tax treaty.

The Supreme Court of Canada described the OECD Model Treaty as being “[o]f high persuasive value in terms of defining the parameters of the Canada-United States Income Tax Convention (1980)”. 8 Crown Forest, above, at p. 5398. There is certainly precedent for a Canadian court to consider the OECD Model Treaty and Commentary as an extrinsic aid when interpreting a Canadian tax treaty. For example, in Prevost Car Inc. v. The Queen, 9 2009 DTC 5053 (FCA), affirming 2008 DTC 3080 (TCC). the Federal Court of Appeal stated:

[10] The worldwide recognition of the provisions of the Model Convention and their incorporation into a majority of bilateral conventions have made the Commentaries on the provisions of the OECD Model a widely-accepted guide to the interpretation and application of the provisions of existing bilateral conventions (see Crown Forest Industries Ltd. v. Canada, [1995] 2 S.C.R. 802; Klaus Vogel, “Klaus Vogel on Double Taxation Conventions” 3rd ed. (The Hague: Kluwer Law International, 1997) at 43.

However, it is important not to treat OECD materials as being equivalent to the law (i.e., the ITA or the text of an actual bilateral tax treaty), which they are clearly not. For example, in Canada v. GlaxoSmithKline Inc., 10 2012 SCC 52, para. 20. the SCC established that while OECD guidelines and commentaries may be a helpful interpretative aid to the courts, they “are not controlling as if they were a Canadian statute and the test of any set of transactions or prices ultimately must be determined according to [s. 247] rather than any particular methodology or commentary set out in the Guidelines.” 11 At para. 20. Moreover, while Canadian courts have frequently cited OECD transfer pricing guidelines when applying Canada’s transfer pricing rules, they have sometimes been reluctant to follow them. That was perhaps stated most clearly in McKesson Canada Corp. v. The Queen, 2013 TCC 404, in which Justice Patrick J. Boyle said:

I would add the observation that OECD Commentaries and Guidelines are written not only by persons who are not legislators, but in fact are the tax collection authorities of the world. Their thoughts should be considered accordingly. For tax administrators, it may make sense to identify transactions to be detected for further audit by the use of economists and their models, formulae and algorithms.

But none of that is ultimately determinative in an appeal to the Courts. The legal provisions of the Act govern and they do not mandate any such tests or approaches. The issue is to be determined through a fact finding and evaluation mission by the Court, as it is in any factually based issue on appeal, having regard to all of the evidence relating to the relevant facts and circumstances.

Ultimately the relevance of OECD guidance will depend on the facts and circumstances, in particular the extent to which the Canadian provisions (treaty or domestic law) being interpreted are the same as those to which the OECD materials relate. For example, in The Queen v. Alta Energy Luxembourg SARL, 12 2020 FCA 43. the Federal Court of Appeal rejected the CRA’s references to the OECD Commentary on Article 13 (Capital Gains) on the basis that the actual treaty being litigated (the Canada-Luxembourg Tax Treaty) simply contained a different test than that found in the corresponding article of the OCED Model Treaty. 13 At para. 36: “The commentaries, to which the Crown referred, relate to an OECD Model Tax Convention that was created after the particular exemption in issue was included in the first convention between Canada and Luxembourg. These commentaries were written for a model convention that was not adopted by Canada and Luxembourg. These commentaries are of little assistance in determining the rationale for the exemption that is in issue in this case.” Similarly, Canadian courts have rejected important elements of the OECD transfer pricing guidelines as being inconsistent with section 247 (for example, the Tax Court’s decision in Cameco rejecting the CRA’s suggestion that managing or monitoring risk is equivalent to actually bearing that risk). 14 For analysis of the decision, see Steve Suarez, “The Cameco Transfer Pricing Decision: A Victory for the Rule of Law and the Canadian Taxpayer,” Tax Notes Int’l, Nov. 26, 2018, p. 877. As such, the OECD Model Treaty and OECD Commentary should be considered when interpreting a Canadian tax treaty, but a court may or may not find them persuasive, depending on the facts.

Other Extrinsic Aids

The U.S. Treasury Department has prepared technical explanations to various iterations of the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty, the most recent of which (the “U.S. Technical Explanation”) was produced following the 2007 Protocol to the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty. The Department of Finance has expressed the view that the U.S. Technical Explanation “accurately reflects understandings reached in the course of negotiations with respect to the interpretation and application of various provisions of the Protocol,” 15 Release 2008-052. such that the U.S. Technical Explanation can be said to also reflect Canada’s interpretation of that treaty. Canadian courts have treated that and prior versions of the U.S. Technical Explanation as a useful source of interpretative guidance in applying the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty. 16 See for example the Crown Forest and Coblentz cases, above; and TD Securities (USA) LLC v. The Queen, 2010 DTC 1137 (TCC).

However, the U.S. Technical Explanation is not itself equivalent to the text of the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty, as was made clear by the Federal Court of Appeal in Canada v. Kubicek Estate: 17 97 DTC 5454 (FCA).

There is no international tradition or procedure for an exchange of subsequently bargained documents as determinative of treaty interpretation. The Technical Explanation is a domestic American document. True, it is stated to have the endorsation of the Canadian Minister of Finance, but in order to bind Canada it would have to amount to another convention, which it does not. From the Canadian viewpoint, it has about the same status as a Revenue Canada interpretation bulletin, of interest to a Court but not necessarily decisive of an issue.

In any event, the document should not be interpreted as if it were a treaty or statute dealing in detail with every possible application to particular facts. The term “held” would be literally accurate in general, but is not qualified to deal with the particular situation of property held in Canada by a U.S. resident prior to 1972.

As such, the U.S. Technical Explanation should be viewed as an interpretative aid the utility of which in any particular case will depend on the facts and circumstances.

Other potential extrinsic aids that have been considered by Canadian tax courts include the United Nations Model Double Taxation Convention 18 See Crown Forest, above; Cloutier v. The Queen, 2003 DTC 317 (TCC), American Income Life Insurance Company v. The Queen; 2008 DTC 3631 (TCC); and Knights of Columbus v. The Queen, 2008 DTC 3648 (TCC). and the U.S. Model Income Tax Convention.19 Cloutier, above; Wolf v. The Queen, 2018 TCC 84. In appropriate cases the courts will hear expert testimony as regards the interpretation of such extrinsic aids. 20 See the Knights of Columbus and American Income Life cases, above, as well as Prevost Car Inc. v. The Queen, 2008 TCC 231; affirmed, 2009 FCA 57. See also Deegan v. Canada 2019 FC 960 (FCTD) (under appeal), in which the Federal Court of Canada considered extensive expert evidence (including from senior Department of Finance officials) in the context of a challenge to the Canada-United States Enhanced Tax Information Exchange Agreement entered into between Canada and the U.S. with regard to the U.S. Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) legislation.

3. Claiming Treaty Benefits

- Being resident for tax purposes in one or the other country (or both) is the basic requirement for claiming benefits under a tax treaty between two countries.

- “Resident for tax purposes” in a particular country is generally defined in each treaty as being subject to tax in that country on one’s worldwide income (whether or not tax is actually paid), not merely being subject to tax on income from that country.

- Being the “beneficial owner” of interest, dividends or royalties is a further requirement in most tax treaties for claiming reduced rates of source country withholding tax. Canadian courts have determined beneficial ownership with reference to (a) possession of; (b) use of; (c) risk from; and (d) control over, the particular payment in question.

- The courts in Canada have rejected CRA attempts to look through the actual recipient of amounts in favour of some other alleged “real” owner unless that actual recipient has no discretion over the use of the amount.

- Canada’s courts have so far rejected an anti-abuse doctrine of “treaty shopping,” instead looking to whether in any particular case the results are inconsistent with the intentions of the treaty countries (as expressed by the text of the treaty and relevant extrinsic aids).

- There is not yet any Canadian judicial guidance on the new “principal purpose test” (PPT) incorporated into most of Canada’s tax treaties under the MLI.

Fiscal Residence

The fundamental requirement for a person to claim treaty benefits under a tax treaty between two countries is to be a resident of one country or the other for purposes of that country’s tax laws. This is set out in Article 1 of Canada’s tax treaties, typically in the following wording:

This Convention shall apply to persons who are residents of one or both of the Contracting States.

Fiscal residence is defined in Article 4 of the tax treaty, generally in a way that requires a resident of a particular country to be subject to tax (whether or not actually taxed) in that country on the person’s worldwide income, not merely on income from sources in that country. Article 4(1) of the Canada-Luxembourg Tax Treaty provides an example of the typical language:

For the purposes of this Convention, the term “resident of a Contracting State” means any person who, under the laws of that State, is liable to tax therein by reason of that person’s domicile, residence, place of management or any other criterion of a similar nature. This term also includes a Contracting State or a political subdivision or local authority thereof or any agency or instrumentality of any such State, subdivision or authority. This term, however, does not include any person who is liable to tax in that State in respect only of income from sources in that State.

This was the issue before the Supreme Court of Canada in the Crown Forest case described above. In Crown Forest, the Canadian taxpayer argued that it was entitled to withhold on rental payments to a Bahamian corporation with a U.S. “place of management” and carrying on business in the U.S. at a treaty-reduced rate, on the basis that the Bahamian corporation was entitled to claim a 10% withholding tax rate as a U.S. resident under the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty (as then in force). The SCC rejected this argument, concluding that a U.S. resident within the meaning of the treaty was limited to persons “to those taxed only on world-wide income” in the U.S. under U.S. domestic law (at 5399):

I see nothing fundamentally unjust with the situation where, owing to the nature of U.S. tax legislation, the Convention would be limited to those who actually incorporated in the U.S. (i.e., those who are actually American residents). After all, why should entities not regarded as “residents” by a contracting state be regarded as residents of that state for the purposes of the Convention?

Tax authorities that believe a particular person should not be entitled to claim treaty benefits often seek to convince a court that some higher standard of nexus with a country should be established to allow that person to claim treaty benefits, notwithstanding the absence of any wording to that effect in the tax treaty. A recent example is the case of The Queen v. Alta Energy Luxembourg SARL 21 2020 FCA 43, affirming 2018 DTC 1120 (TCC); currently under appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada. in which the CRA challenged the taxpayer’s claim of an exemption from Canadian capital gains tax under Article 13(4) of the Canada-Luxembourg tax treaty. Article 13(4) and (5) of that treaty read as follows:

4. Gains derived by a resident of a Contracting State from the alienation of:

(a) shares (other than shares listed on an approved stock exchange in the other Contracting State) forming part of a substantial interest in the capital stock of a company the value of which shares is derived principally from immovable property situated in that other State; or

(b) an interest in a partnership, trust or estate, the value of which is derived principally from immovable property situated in that other State, may be taxed in that other State. For the purposes of this paragraph, the term “immovable property” does not include property (other than rental property) in which the business of the company, partnership, trust or estate was carried on; and a substantial interest exists when the resident and persons related thereto own 10 per cent or more of the shares of any class or the capital stock of a company.

5. Gains from the alienation of any property, other than that referred to in paragraphs 1 to 4 shall be taxable only in the Contracting State of which the alienator is a resident.

In that case, the Crown sought to elevate the threshold for claiming treaty benefits (or at least the benefit of this particular article of that treaty) to something more than merely being a fiscal resident of Luxembourg. Instead, the Crown took the position in its memorandum of law that the “underlying rationale” of these provisions was that Article 13(4) be limited to Luxembourg-resident “investors”

Articles 1, 4 and 13(4) of the Convention, together, are intended to grant a particular treaty benefit to Luxembourg investors whose investments in specific taxable Canadian property gives rise to gains for them, in Luxembourg. Those provisions are not intended to benefit entities who do not have the potential to realize income in Luxembourg, nor have any commercial or economic ties therewith. Such situations are wholly dissimilar to the relationships or transactions that are contemplated by those provisions of the Convention.

The FCA rejected this argument, observing that the text of the relevant treaty provisions clearly referred to “residents”, and that the Crown had “not provide[d] any explanation for why ‘investor’ was substituted for ‘resident’.” As such, the Court refused to read into the treaty words that did not exist without a clear and unambiguous expression of the treaty parties’ intent requiring such in order to give effect to their intentions:

[49 ] It does not seem to me that claiming the exemption from tax in Canada, on the gain realized on a sale of shares of a particular company, is predicated on the resident of Luxembourg having made any particular investment in that company. To add a requirement that the resident of Luxembourg must have made an investment in the relevant company, would then require speculation on the amount and the source of such investment that would be necessary for the person to be eligible for the exemption from tax in Canada. The requirements of the Luxembourg Convention are simply that the person claiming the exemption (who holds a substantial interest) is a resident of Luxembourg, and that the company (whose shares were sold) satisfies the asset test as set out in Article 13(4). There are no further requirements.

. . .

[52] . . . If, in applying the GAAR, an additional requirement is inferred that the resident of Luxembourg must invest in the corporation in order to qualify for the exemption, this could lead to the result that it would be an abuse of the Luxembourg Convention, if the person did not invest in the particular corporation. This would result in a significant change in the requirements that the resident of Luxembourg would have to satisfy. In my view, the addition of this requirement is not warranted. There is nothing to suggest that the underlying rationale for the exemption is that it would only be available to a resident of Luxembourg who invests in the particular corporation in which such resident holds shares.

[53] Article 13(4) applies to the residents of each contracting state. If a person is a resident of Luxembourg as defined in Article 4, then that person is also a resident for the purposes of Article 13(4). The Crown does not dispute that Alta Luxembourg was a resident of Luxembourg for the purposes of the Luxembourg Convention. This is sufficient to satisfy this requirement as set out in Article 13(4), without any necessity to determine what, if any, amounts Alta Luxembourg invested in Alta Canada.

Fundamentally, Canadian courts have interpreted treaties on the basis that the parties thereto have chosen the words they use in a treaty for a reason, and are reluctant to read into a treaty text that is not present and which would materially change the apparent bargain agreed to by the treaty countries. The basic requirement of fiscal residence for entitlement to treaty benefits is no exception to this principle.

Beneficial Ownership

A number of tax treaty provisions make reference to the beneficial owner of a particular payment or property being entitled to a reduced rate of source country taxation. Such reference is most commonly found in the treaty articles dealing with dividends (Article 10), interest (Article 11) and royalties (Article 12).

In The Queen v. Prevost Car Inc., 22 2008 TCC 231; affirmed, 2009 FCA 57. the CRA challenged a Canadian corporation (“Prevost Car”) that paid dividends to its Dutch parent company (“Prevost Holdings”) at a treaty-reduced rate of 5%. The shareholders or Prevost Holdings were a Swedish corporation (“Volvo”) and a U.K. corporation (“Henlys”) to which a higher Canadian withholding tax rate would apply. Volvo and Henlys had entered into a shareholders agreement setting out that not less than 80% of the profits of Prevost Car/Prevost Holdings would be distributed to the two shareholders as soon as practicable after year-end. This was subsequently refined by further agreement between Volvo and Henlys.

Article 10(2) of the Canada-Netherlands Tax Treaty provided for a 10% rate of Canadian withholding tax if the “beneficial owner” of the dividend was a Dutch resident meeting certain conditions. The CRA took the position that Prevost Holdings was not the “beneficial owner” of dividends received from Prevost Car (apparently contrary to the views of Dutch tax authorities), and that rather Volvo and Henlys were the beneficial owners, on the basis that those two entities were the persons that ultimately enjoy or benefit from them. In this regard, the CRA accepted that Prevost Holdings was not an agent, trustee or nominee for Volvo and Henlys, but was a “mere conduit or funnel” in favour of its two shareholders. 23 Para. 94, TCC decision

The Tax Court judge concluded that the term “beneficial owner” should be determined with reference to the legal attributes of ownership:

[100] In my view the “beneficial owner” of dividends is the person who receives the dividends for his or her own use and enjoyment and assumes the risk and control of the dividend he or she received. The person who is beneficial owner of the dividend is the person who enjoys and assumes all the attributes of ownership. In short the dividend is for the owner’s own benefit and this person is not accountable to anyone for how he or she deals with the dividend income. . . . Where an agency or mandate exists or the property is in the name of a nominee, one looks to find on whose behalf the agent or mandatary is acting or for whom the nominee has lent his or her name. When corporate entities are concerned, one does not pierce the corporate veil unless the corporation is a conduit for another person and has absolutely no discretion as to the use or application of funds put through it as conduit, or has agreed to act on someone else’s behalf pursuant to that person’s instructions without any right to do other than what that person instructs it, for example, a stockbroker who is the registered owner of the shares it holds for clients. This is not the relationship between PHB.V. [Prevost Holdings] and its shareholders.

On the facts at hand, Prevost Holdings met the requirements to be considered the beneficial owner of dividends paid on the shares of Prevost Car:

[105] PHB.V. [Prevost Holdings] was the registered owner of Prévost shares. It paid for the shares. It owned the shares for itself. When dividends are received by PHB.V. in respect of shares it owns, the dividends are the property of PHB.V. Until such time as the management board declares an interim dividend and the dividend is approved by the shareholders, the monies represented by the dividend continue to be property of, and is owned solely by, PHB.V. The dividends are an asset of PHB.V. and are available to its creditors, if any. No other person other than PHB.V. has an interest in the dividends received from Prévost. PHB.V. can use the dividends as it wishes and is not accountable to its shareholders except by virtue of the laws of the Netherlands. Volvo and Henlys only obtain a right to dividends that are properly declared and paid by PHB.V. itself, notwithstanding that the payment of the dividend has been mandated to TIM. Any amount paid by PHB.V. to Henlys and Volvo before a dividend was properly declared and paid, as I see it, was a loan from PHB.V. to its shareholders. This, too, is not uncommon. There is a practice in Canada of corporations advancing funds to its shareholders without a declaration of dividend. At the end of the fiscal year, the corporation’s directors determine whether the funds are to remain a loan or be “adjusted” to a dividend, with the proper directors’ resolutions. This practice, I understand, is accepted by the fisc[.]

The Federal Court of Appeal agreed, rejecting the Crown’s appeal and summarizing the Tax Court’s relevant findings as follows:

[16] The Judge found that:

a) the relationship between Prévost Holding and its shareholders is not one of agency, or mandate nor one where the property is in the name of a nominee (par. 100);

b) the corporate veil should not be pierced because Prévost Holding is not “a conduit for another person”, cannot be said to have “absolutely no discretion as to the use or application of funds put through it as a conduit” and has not “agreed to act on someone else’s behalf pursuant to that person’s instructions without any right to do other than what that person instructs it, for example a stockbroker who is the registered owner of the shares it holds for clients” (par. 100);

c) there is no evidence that Prévost Holding was a conduit for Volvo and Henlys and there was no predetermined or automatic flow of funds to Volvo and Henlys (par. 102);

d) Prévost Holding was a statutory entity carrying on business operations and corporate activity in accordance with the Dutch law under which it was constituted (par. 103);

e) Prévost Holding was not party to the Shareholders’ Agreement (par. 103);

f) neither Henlys nor Volvo could take action against Prévost Holding for failure to follow the dividend policy described in the Shareholders’ Agreement (par. 103);

g) Prévost Holding’s Deed of Incorporation did not obligate it to pay any dividend to its shareholders (par. 104);

h) when Prévost Holding decides to pay dividends, it must pay the dividends in accordance with the Dutch law (par. 104);

i) Prévost Holding was the registered owner of Prévost shares, paid for the shares and owned the shares for itself; when dividends are received by Prévost Holding in respect of shares it owns, the dividends are the property of Prévost Holding and are available to its creditors, if any, until such time as the management board declares a dividend and the dividend is approved by the shareholders (par. 105).

In particular, the FCA expressed grave concern with the CRA’s willingness to ignore holding companies and simply ignore the legal owners of property:

The Crown, it seems to me, is asking the Court to adopt a pejorative view of holding companies which neither Canadian domestic law, the international community nor the Canadian government through the process of objection, have adopted.

The CRA took another run at this issue in Velcro Canada Inc. v. The Queen. 24 2012 TCC 57. In that case, the Canadian taxpayer (VCI) paid royalties to a Dutch entity (VHBV) that in turn paid 90% of those royalties to a related entity (VIBV) resident in the Dutch Antilles that had assigned to VHBV the licence with the Canadian taxpayer. The Crown re-assessed the Canadian taxpayer to deny the 10% royalty withholding tax rate found in the Canada-Netherlands Tax Treaty, on the following bases:

1. VHBV did not beneficially own the royalties;

2. VHBV was an agent or conduit;

3. VHBV did not exercise the “incidences of ownership” as required by Prevost, supra.

The Tax Court’s judgment goes through the evidence in considerable detail, and lays out in systematic fashion the criteria that taxpayers (and tax authorities) should look to in satisfying themselves that the intended party will be considered be the “beneficial owner” of a payment or property, based on the possession, use, risk and control thereof:

[29] From Prévost, there are really four elements in considering the attribution of beneficial ownership and those are: (a) possession; (b) use; (c) risk; and (d) control. The question therefore is, did VHBV have possession, use, risk and control of the royalties from VCI, considering, (a) the License Agreement; (b) the Assignment Agreement; (c) the New License Agreement; (d) the new Assignment Agreement; (e) the flow of funds; and (f) the financial statements and bank statements of VHBV. These are the key instruments or documents that one must look to determine who has the possession, use, risk and control of the royalties in question. Also, it is important to emphasize that, as Chief Justice Rip in Prévost noted, the Court is not likely to pierce the corporate veil unless the corporation has no discretion with regard to the use and application of the funds. The Court will look at whether the party in question exercised or held the attributes of beneficial ownership in regards to the royalty payments.

. . .

[34] In looking at the beneficial ownership issue one must apply the test as set out by Chief Justice Rip, and in doing so, one must look to the meaning of individual words, that is, “possession”, “use”, “risk” and “control”. These words have ordinary meanings.

[35] When one looks to the word “possession” in Black’s Law Dictionary, it speaks in terms of “having or holding property in one’s power” or “the exercise of dominion over property”. How did VHBV exercise dominion over the royalties received from VCI? There are a number of ways that VHBV exercised dominion over the royalties:

1. Through the interaction between the license agreements and the assignment agreements, VHBV had the right to receive the royalties.

2. The royalties were deposited into an account, in Canadian funds, owned by VHBV.

3. VHBV had exclusive possession and control over these accounts.

4. The royalties themselves were not subrogated from other monies of VHBV. The royalties were intermingled and moved with other monies flowing in and out of VHBV accounts.

5. The amounts typically went from Canadian dollars into U.S. dollar accounts and were sometimes converted the next day or later at some other time.

6. VHBV converted the money eventually and moved it into the U.S. account.

7. When the money was in VHBV accounts, the monies earned interest which was earned to the credit of VHBV and not someone else or some other entity.

8. Various charges were deducted from VHBV’s accounts and these are items which VHBV was liable for, including telephone bills, professional fees, and loan payments. These payments came out of the accounts of VHBV.

9. Sometimes the money went into a U.S. deposit account and at other times, into a Dutch currency account and it appears that there was really an unrestricted flow of funds from and between the accounts.

11. VHBV did not have to seek instructions on every step of the application of the funds from someone else.

12. There was co-mingling of the funds with the general funds of VHBV.

13. The royalty payment received by VHBV from VCI was one amount, while the amount paid by VHBV to VIBV was a different amount. The royalties did not simply go in and come out in an automated fashion.

[36] The term “use” in Black’s Law Dictionary makes reference to the application or employment of something: “a long continued possession or employment of a thing for which it is adapted”.

[37] Did VHBV “use” the royalties in the ordinary sense? Did it apply the royalty payments to its own benefit? Reference may be made to the facts referred to in paragraph [35] in discussing the issue of possession. The cash flow statements introduced by the Appellant during the course of trial show that the royalties were co-mingled with other monies and used to do a variety of things:

(a) pay bills and fees;

(b) re-pay loans;

(c) earn interest income for the benefit of VHBV;

(d) invest in new enterprises;

(e) make payments under legal obligations.

[38] Nothing in the License Agreement, New License Agreement, Assignment Agreement or New Assignment Agreement prevents VHBV from using the royalties – they were not segregated in any way, they were co-mingled with other funds and they were used on an operational basis as VHBV saw fit. There were no restrictions on the use of the funds – VHBV only had to meet certain contractual obligations with respect to monies it contractually owed to VIBV.

[39] In Black’s Law Dictionary, “risk” refers to “the chance of injury, damage or loss” or “liability for injury, damage or loss that occurs”. Reference here would be to economic loss.

[40] VHBV did assume some risk in relation to the royalties. There was currency risk in that the monies were received by VHBV in Canadian funds, converted eventually to U.S. funds or Dutch funds. Nothing in any of the agreements referred to shifting any currency risk to anyone else from VHBV. The royalties were the assets of VHBV. They were available to creditors and were shown as such on their financial statements. VHBV reported these funds as assets on their financial statements and therefore were at risk of seizure or availability to creditors, with no priority given to VIBV as a creditor. There was also no indemnification in any of the agreements to reduce the risks and exposure of VHBV.

[41] Finally reference can be made to “control” and the definition of control as found in the Black’s Law Dictionary is “to exercise power or influence over”.

[42] Many of the comments referred to in the interpretation of the phrases “possession”, “use” and “risk”, equally apply to “control”. It was noted that the royalties did not just flow through VHBV but, at the discretion of VHBV, the payments were co-mingled with other funds of VHBV and were subject to the risk of creditors the same as its other assets. VHBV exercised its control, subjecting the funds to increases or decreases by virtue of earning interest or losing value because of the risk of currency exchange and using the funds, in part, to pay other outstanding obligations of VHBV.

[43] The Respondent asserts that VHBV is not the beneficial owner of the royalties, and make reference to the incidences of beneficial ownership. They refer to the use and enjoyment of the royalties, but it is not 100% of the royalties amount that are paid to VIBV but only approximately 90%. The other 10% is subject to the discretionary use, enjoyment, and control of VHBV, assuming it is using the exact same funds, which is not necessarily the case because of the co-mingling of royalty funds with the general funds of VHBV. VHBV also uses, enjoys, and controls funds through currency exchanges and possible investment of some of the royalty payments. Also, VHBV assumes the risk of the royalty payments and certainly the control as is indicated by (a) the co-mingling of the funds with its other assets; (b) being subject to fluctuating currency rates; and (c) the fact that VHBV can invest the funds and earn interest income, and use some of the funds if not all of the funds, to meet its other financial obligations; these facts are all attributes of risk assumption.

[44] VHBV did have an obligation to pay a certain amount of money to VIBV which was equivalent to 90% of the royalties received. The funds paid were not necessarily the same funds as the royalty payments received because the original payments were co-mingled with other assets of VHBV. The funds paid to VIBV were not necessarily in the same dollar because if the funds were converted from Canadian dollars to U.S. dollars or to Dutch currency, it may have been a different amount because of the currency exchange.

[45] Despite the Respondent’s assertion to the contrary, there was no predetermined flow of funds. What there is is a contractual obligation by VHBV to pay to VIBV a certain amount of monies within a specified time frame. These monies are not necessarily identified as specific monies, they may be identified as a percentage of a certain amount received by VHBV from VCI, but there is no automated flow of specific monies because of the discretion of VHBV with respect to the use of these monies.

The Crown was thus unsuccessful in establishing that VIBV was indeed the beneficial owner of the royalties from Canada. The Tax Court also rejected the Crown’s assertions that VHBV was an agent, conduit or nominee acting on behalf of VIBV:

[48] VHBV did not have the capacity to affect the legal position of VIBV and therefore was not a legal agent. In the Assignment Agreements there was a provision that VHBV could not amend the subject agreement or waive the enforcement of any provision without the express prior written consent of VIBV and further, there was no amendment or waiver of the agreement or any provision thereof to be affected unless it was assigned by the party against whom the enforcement of such an amendment or waiver was sought. Further, VHBV could not assign the agreements without the prior written consent of VIBV. If you are going to be able to affect the legal position you should be able to assign or amend and VHBV could do neither.

[49] Notwithstanding that VHBV was obligated to enforce the licensing agreements and notify VIBV of any breaches and take steps to remedy the breach unless directed otherwise by VIBV, and notwithstanding that VIBV had the right to inspect and audit VHBV’s books and that VHBV was contractually required under the assignment and license agreements to take such action as VIBV may reasonably request to secure and protect the rights of VIBV, the key to an agency relationship is that the agent has the ability to affect the legal position of the other. This is not the case with respect to VIBV in relation to VHBV.

[50] In terms of nominee, Black’s Law Dictionary refers to a “nominee” as “a person designated to act in place of another, usually in a limited way”. There was no evidence presented to the Court that VHBV acted in a limited way on the facts. In fact, VHBV acted on its own account at all times subject to the assignment agreements.

[51] In terms of a conduit, the Canadian Oxford Dictionary defines “conduit” as “a channel or pipe that contains liquids”, “a person or organization … through which anything is conveyed (the mediator was a conduit for communication for the parties)”. There is nothing in the agreements to suggest that VHBV was a mere channel. The financial statements fail to show that VHBV is a mere agent, nominee or conduit – quite the contrary. For the Court to find that VHBV was a conduit, there would have to have been no discretion with respect to the funds.

[52] VHBV obviously has some discretion based on the facts as noted above regarding the use and application of the royalty funds. It is quite obvious that though there might be limited discretion, VHBV does have discretion. According to Prévost, there must be “absolutely no discretion” – that is not the case on the facts before the Court. It is only when there is “absolutely no discretion” that the Court take the draconian step of piercing the corporate veil.

The Prevost Car and Velcro decisions remain the controlling authorities in Canada on what constitutes “beneficial ownership” within the meaning of a Canadian tax treaty, and provide taxpayers with excellent guidance on how to meet the requirements for reduced Canadian withholding rates based on beneficial ownership. The U.S. Technical Explanation to the anti-hybrid rules in Articles IV(6) and (7) of the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty contain specific comments on the interaction of those provisions with the “beneficial ownership” concept, which the CRA also adopts. 25 See CRA document 2012-0444041C6, dated 17 May, 2012.

Treaty Shopping

The term “treaty shopping” is frequently used by tax authorities to describe various forms of tax planning involving the use of tax treaties. While this term is rarely defined with precision, at its heart it refers to situations in which a taxpayer claiming the reduction or elimination of source country tax under a tax treaty is perceived by tax authorities to be someone other than a person who the treaty countries “intended” to be able to claim such reduction. Most typically this situation arises where tax authorities believe the existence or fiscal residence of the taxpayer claiming the treaty benefit was motivated primarily by the desire to claim those benefits.

In 2013 the Department of Finance proposed to enact a domestic treaty shopping provision that would amend the Income Tax Conventions Interpretation Act to deny tax treaty benefits in situations where “one of the main purposes” of undertaking a transaction that results in a tax treaty benefit is obtaining that benefit. This remarkable legislative initiative would have amounted to a unilateral repudiation of Canada’s tax treaties, by denying treaty benefits outside of the terms of the tax treaties Canada has agreed to and without consultation. This proposal was the subject of considerable criticism, and was ultimately withdrawn in favour of a the multilateral solution of pursuing the BEPS process. It should nonetheless be observed that the “back-to-back” rules applicable to Canadian withholding tax on interest and royalties effectively constitute a domestic anti-treaty shopping rule as regards those forms of income.

The impetus for the Department of Finance’s 2013 proposal was the government’s dissatisfaction with the results of the three cases that had been heard by the courts to that date:

- MIL (Investments) S.A. v. The Queen, 26 2006 TCC 460; aff’d, 2007 FCA 236. in which a company originally resident in a non-treaty country continued itself into a tax treaty country and claimed the capital gains exemption under that country’s treaty with Canada;

- Prévost Car Inc. v. The Queen, 27 2008 TCC 231, aff’d, 2009 FCA 57. discussed above with reference to beneficial ownership; and

- Velcro Canada Inc. v. The Queen, 28 2012 TCC 273. also discussed above with reference to beneficial ownership.

“Treaty shopping” was formally raised (via the domestic general anti-avoidance rule (“GAAR”)) as such only in the MIL case, although all three cases represented situations in which the CRA believed the taxpayer’s use of the relevant tax treaty was inappropriate and that the “true” owner of the property or payment in question was someone other than the non-resident claiming the tax treaty benefit.

Subsequent to those cases, the CRA tried another treaty shopping case, The Queen v. Alta Energy Luxembourg SARL 29 2020 FCA 43, affirming 2018 DTC 1120 (TCC); currently under appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada. (discussed above with reference to fiscal residence). In Alta Energy, the CRA sought to apply the general anti-avoidance rule (GAAR) in s. 245 ITA to deny a Luxembourg resident the benefit of the exemption from Canadian capital gains tax in Article 13(4) of the Canada-Luxembourg Tax Treaty, on the basis that such claim was abuse of those articles of that treaty.

As noted above with reference to the concept of fiscal residence, the Court rejected the CRA’s assertion that the intention of the treaty countries was to limit the capital gains exemption to situations in which the non-resident claiming the treaty benefit had made a direct investment into Canada (as opposed to purchasing an existing investment into Canada). The CRA also argued that the noted that Luxembourg would not tax the capital gain in question, meaning that if Canada was not able to tax the gain, it would not be taxed at all. This result, it was argued, was not consistent with the intention of the treaty countries. This again was rejected by the Court both as a back-door attempt to create a standard beyond residency for claiming treaty benefits (i.e., actual taxes owing in Luxembourg) and as being a result that would have been known to Canada when it agreed to cede its right to tax capital gains in these circumstances. 30 At para 61: “By conceding that Alta Luxembourg is a resident of Luxembourg for the purposes of the Luxembourg Convention, the Crown is conceding that Alta Luxembourg was liable for tax in Luxembourg. The Crown cannot now indirectly argue that Alta Luxembourg was not liable for tax in Luxembourg.”

Finally, the FCA disposed of the Crown’s argument that the underlying purposes of the capital gains exemption was meant to benefit only persons who have commercial or economic ties to Luxembourg, on largely the same grounds (at para. 65):

Since there is no dispute that Alta Luxembourg is a resident of Luxembourg, it is entitled to claim the benefit of Articles 13(4) and (5) of the Luxembourg Convention. There is no distinction in the Luxembourg Convention between residents with strong economic or commercial ties and those with weak or no commercial or economic ties. If a person satisfies the definition of resident in Article 4, then that person is a resident for the purposes of Articles 13(4) and (5). The Crown did not provide any support for its contention that the object, spirit and purpose of Articles 13(4) and (5) was only to exclude from taxation in Canada gains arising from the disposition of shares held by Luxembourg residents with strong economic or commercial ties to Luxembourg.

With respect to a specific appeal to treaty shopping as a specific anti-avoidance doctrine, the FCA made the following observations:

[75] . . . The only direct reference to “treaty shopping” in the Crown’s memorandum (other than in a footnote) is in paragraph 61:

61. The Government of Canada has, for many years, consistently expressed the position that it would challenge abusive treaty shopping arrangements, including by having recourse to the GAAR. In addition, many of Canada’s tax treaties contain specific provisions that are intended to limit treaty abuses. For example some of Canada’s treaties contain provisions that limit access to treaty benefits (e.g. by denying treaty benefits for certain types of entities, or with respect to certain transactions). However, such provisions do not preclude the application of the GAAR to counter the abusive use of the provisions of the treaty.

. . .

[78] With respect to treaty shopping, the Tax Court Judge in MIL (Investments) S.A. noted that:

[72] In written argument, Respondent’s counsel argued that ‘treaty shopping’ is an abuse of bilateral tax conventions and that this is recognized by the Supreme Court of Canada. In oral argument, the following passage from Crown Forest Industries Limited v. The Queen, [1995] 2 S.C.R. 802 at page 825, was quoted to establish that if the Supreme Court had access to section 245, it would have used that section to deny a benefit from “treaty shopping”:

It seems to me that both Norsk and the respondent are seeking to minimize their tax liability by picking and choosing the international tax regimes most immediately beneficial to them. Although there is nothing improper with such behaviour, I certainly believe that it is not to be encouraged or promoted by judicial interpretation of existing agreements …

I do not agree that Justice Iaccobucci’s obiter dicta can be used to establish a prima facie finding of abuse arising from the choice of the most beneficial treaty. There is nothing inherently proper or improper with selecting one foreign regime over another. Respondent’s counsel was correct in arguing that the selection of a low tax jurisdiction may speak persuasively as evidence of a tax purpose for an alleged avoidance transaction, but the shopping or selection of a treaty to minimize tax on its own cannot be viewed as being abusive. It is the use of the selected treaty that must be examined.

(emphasis in original and footnote references have been omitted)

[79] The issue and arguments of the Crown, in this case, were consistent with these comments, as the Crown focused on the provisions of the Luxembourg Convention itself.

[80] I agree with the decision of this Court in MIL (Investments) S.A. that the object, spirit and purpose of the relevant provisions of the Luxembourg Convention is reflected in the words as chosen by Canada and Luxembourg. Since the provisions operated as they were intended to operate, there was no abuse.

Pending the SCC’s hearing of the Crown’s appeal in Alta Energy, it would seem fairly clear that there is no stand-alone anti-“treaty shopping” doctrine in the Canadian jurisprudence. Instead, in any given case, the courts will look to the words of the treaty and any relevant extrinsic evidence to determine whether they believe the result sought by the taxpayer is inconsistent with the intentions of the treaty countries.

MLI: The New PPT

Canada has adopted the principal purpose test (PPT) in Article 7(1) of the MLI as its general treaty anti-abuse measure, while indicating that in so doing as an interim measure, it intends where possible to adopt a limitation on benefits provision, in addition to or in replacement of the PPT through bilateral negotiation. 31 Ibid. The PPT reads as follows:

Notwithstanding any provisions of a Covered Tax Agreement, a benefit under the Covered Tax Agreement shall not be granted in respect of an item of income or capital if it is reasonable to conclude, having regard to all relevant facts and circumstances, that obtaining that benefit was one of the principal purposes of any arrangement or transaction that resulted directly or indirectly in that benefit, unless it is established that granting that benefit in these circumstances would be in accordance with the object and purpose of the relevant provisions of the Covered Tax Agreement.

As a result, for covered tax agreements with counterparties that do not adopt a contrary position, the PPT will limit a treaty resident’s ability to claim relief under the terms of the treaty. The use of PPTs in Canada’s tax treaties is very limited prior to the MLI, and no Canadian judicial guidance exists as yet on the interpretation of PPTs in Canada’s tax treaties. 32 For a discussion of how Canada’s courts might interpret the PPT under the MLI, see (1) Heale, Gagnon and Tonkovich, “The Multilateral Instrument’s Principal Purpose Test: Changing Tax Disputes for the Future, Not the Past,” Tax Litigation, Vol. XXIII, No. 2 (Federated Press); (2) Kandev and Lennard, “The OECD Multilateral Instrument: A Canadian Perspective on the Principal Purpose Test,” Bulletin for International Taxation, 2020 (vol. 74), No.1; (3) ; Boidman and Kandev, “Canada Enacts Multilateral Instrument: What Happens Next?” Tax Notes Int’l, July 22, 2019, p. 315; and (4) Duff, “Tax Treaty Abuse and the Principal Purpose Test – Part 1,” 66(3) Canadian Tax Journal p. 619; and “Part 2,” 66(4) Canadian Tax Journal p. 947.

There is no Canadian caselaw on the interpretation of the PPT, which will likely take several years to develop as taxation years in which it is effective in Canada are audited by the CRA and re-assessed. Very little CRA interpretative guidance also exists. The only significant CRA statement 33 CRA document 2020-0862471C6, dated 27 October 2020 to date states that the CRA would look for guidance to the various examples of when the PPT would and would not apply provided in the OECD Commentary to Article 29. That CRA statement also sets out the following indicia that the CRA would look to in applying the PPT:

Much of the concern expressed about uncertainty and the potential application of the PPT appears to center around questions as to the necessary indicia to support or rebut a reasonable conclusion that a transaction or arrangement had a principal purpose of obtaining a benefit under a tax convention, or what is required to establish that granting the benefits would nevertheless be in accordance with the relevant provisions of the convention in the particular circumstances.

As explained in paragraphs 178 to 181 of the OECD Commentary to Article 29, these questions are highly fact-dependent and linked to the particular taxpayers and their motives as well as the specific tax convention and the provisions and benefits thereunder in question.

In determining whether any arrangement or transaction has, as one of its principal purposes, the obtaining of a treaty benefit, the CRA would seek to ask a number of questions, including but not limited to:

* What are the direct and indirect results of the arrangement?

* What are the terms of the arrangement and do they lead to its results?

* What actions were undertaken to carry the arrangement into effect?

* What do the circumstances surrounding the arrangement, the way in which it was implemented, as well as its terms, indicate about the arrangement and its intended results?

* Could the non-tax objectives of the arrangement be achieved some other way? If so, is the arrangement more complex, more costly (not considering the tax benefit), or contain more steps than is necessary to achieve the non-tax objectives?

* Does the arrangement entail the use of hybrid entities, flow-through arrangements, or back-to-back transactions?

* Does the arrangement involve a change of residence or applicable tax convention?

* What are the non-tax benefit purposes for establishing each of the relevant entities or actions in each relevant jurisdiction?

* Is the existence of any entity or action in the arrangement explainable only if it is principally concerned with obtaining the relevant benefit?

* Absent any tax benefit, are there quantifiable financial benefits arising from the arrangement?

* Is there a discrepancy between the substance of what the arrangement achieves and its legal form?

* Does the arrangement result in a change in nature of payments?

* Does the arrangement result in the avoidance of a specific taxing rule? For example, does it avoid the existence of a permanent establishment or to avoid a test which would otherwise limit access to a benefit?

The above questions may also be relevant in respect of the GAAR for taxation years currently audited.

CRA Forms NR301, NR302 and NR303

The CRA has issued forms intended for use whenever a payer of amounts that are potentially subject to Canadian non-resident withholding tax (for example, interest, dividends, or royalties) withholds and remits at a rate less than that called for under Part XIII on the basis that the recipient is entitled to a reduced rate of tax under a bilateral tax treaty. While the use of these forms is not mandatory for payers to withhold at a reduced rate, they indicate what kind of diligence the CRA expects payers to undertake before withholding at a reduced rate based on a treaty exemption. Three forms exist:

- NR301, for non-residents that are neither partner-ships nor hybrid entities;

- NR302, for partnerships with non-resident partners; and

- NR303, for hybrid entities such as U.S. LLCs that are disregarded for U.S. tax purposes

The CRA website discusses the requirements for withholding under Part XIII at a treaty-reduced rate and includes various questions and answers with respect to these forms.

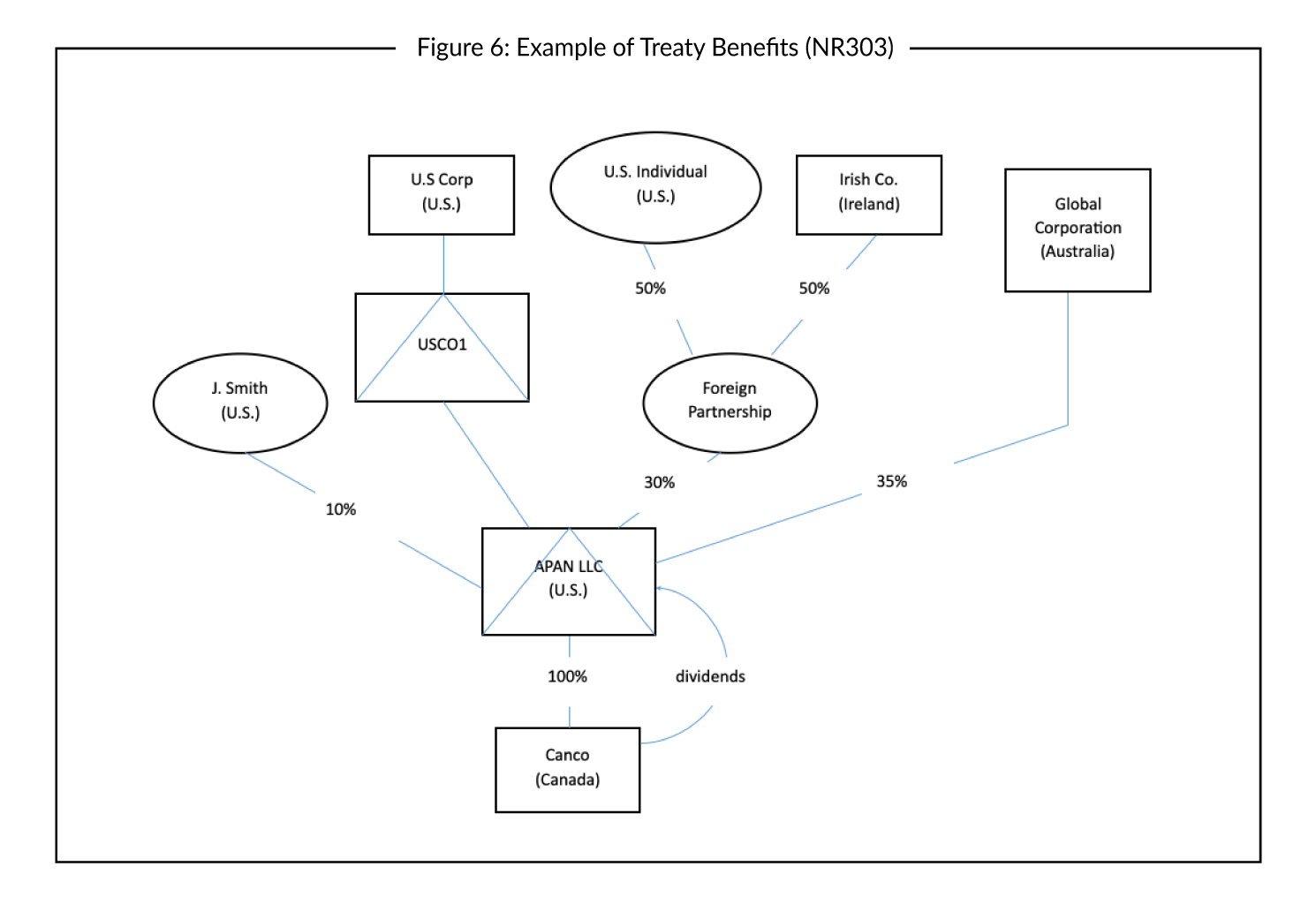

The use of these forms is not mandatory, although they a helpful resource on the information the CRA views as relevant to determining eligibility for treaty benefits, as well as examples of the application of the relevant rules. The example provided in NR303 dealing with hybrids is illustrated in Figure 6, and discussed in further depth below under 4. The Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty, Hybrids: LLCs and ULCs . For this purpose a hybrid is defined as a foreign entity (other than a partnership) not entitled to treaty benefits in its own right, but the members/owners of which are entitled to claim treaty benefits through (e.g., U.S. LLCs).

4. The Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty

- There are a number of features in the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty that are unique among Canada’s tax treaties, including the presence of an official Technical Explanation and a variety of subsidiary agreements on various issues between Canada and the U.S..

- The Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty is the only Canadian tax treaty with a limitation on benefits (LOB) clause restricting access to treaty benefits.

- Where both Canada and the U.S. claim a corporation to be resident, a definitive tie-breaker deems it to be resident for treaty purposes only in the country under whose laws it derives its existence from.

- The Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty is the only Canadian tax treaty with a zero % interest withholding rate (except for participating interest).

- The Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty is the only Canadian tax treaty with a “services permanent establishment” rule in Article V.

- Article IV of the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty contains important rules dealing with limited liability companies (LLCs) and hybrid entities (i.e., fiscally transparent in one country and treated as taxable entities in the other), such as Canadian unlimited liability companies (ULCs).

Because the U.S. is Canada’s largest trading partner and source of imported capital, the Canada U.S. Treaty is Canada’s most important bilateral tax agreement. While this tax treaty follows the general format of Canada’s other tax treaties for the most part, there are a number of unusual or unique elements in this treaty, which are discussed below.

Note: a variety of legal and administrative agreements pertaining to taxes exist between Canada and the U.S. These can be found on the Useful Links page.

Technical Explanation

As noted above under 2. Treaty Interpretation in Canada, the U.S. Treasury Department has prepared technical explanations to various iterations of the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty, the most recent of which (the “U.S. Technical Explanation”) was produced following the 2007 Protocol to the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty. The Department of Finance has expressed the view that the U.S. Technical Explanation “accurately reflects understandings reached in the course of negotiations with respect to the interpretation and application of various provisions of the Protocol,” 34 Release 2008-052. such that the U.S. Technical Explanation can be said to also reflect Canada’s interpretation of that treaty. While not equivalent to the treaty text itself, the U.S. Technical Explanation is nonetheless an important source of interpretive guidance.

The Limitation on Benefits (LOB) Article

The Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty is Canada’s only tax treaty that restricts treaty benefits using a limitation on benefits (LOB) article. The LOB article raises the requirement for claiming treaty benefit to a higher standard above merely being a “resident” for tax purposes in one country or the other, and imposes additional tests for claiming any benefits under the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty. As such, it is a very important substantive element of that treaty.

A detailed discussion of the LOB article in the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty can be found here.

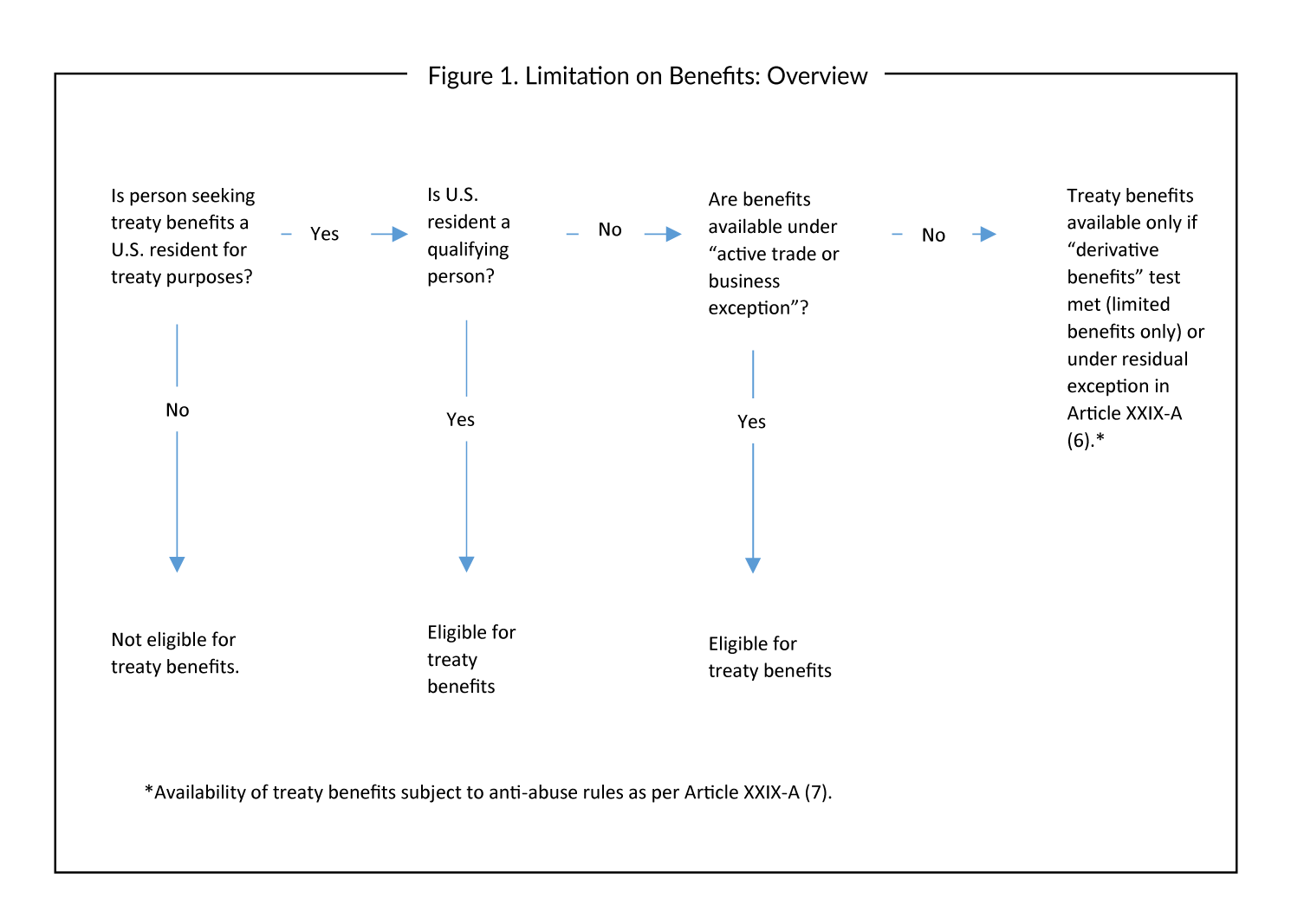

The basic framework of the LOB clause in the treaty (Article XXIX-A) is as follows:

- Paragraph 1: a general rule limiting the claiming of treaty benefits to “qualifying persons,” a term defined in paragraph 2.

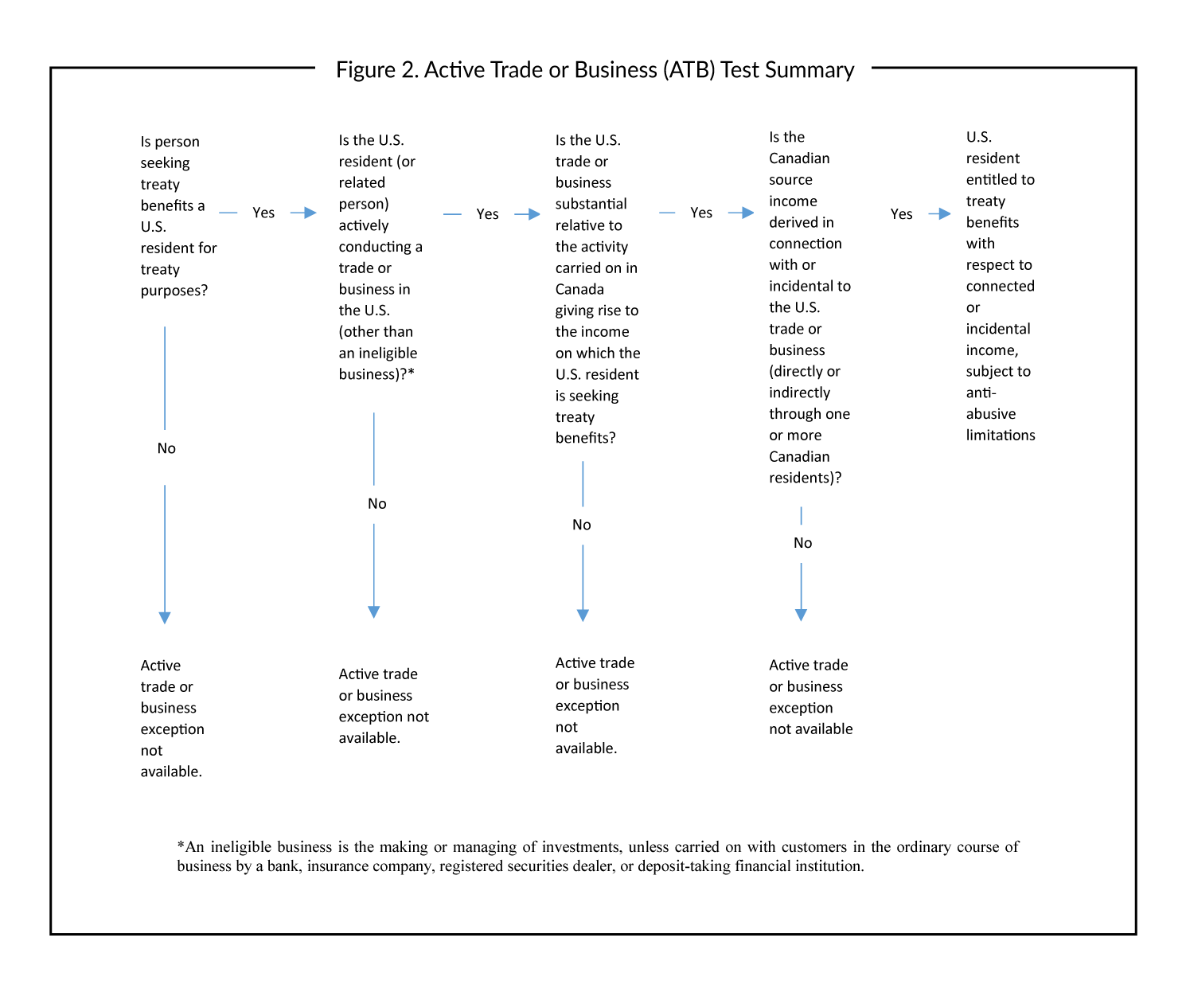

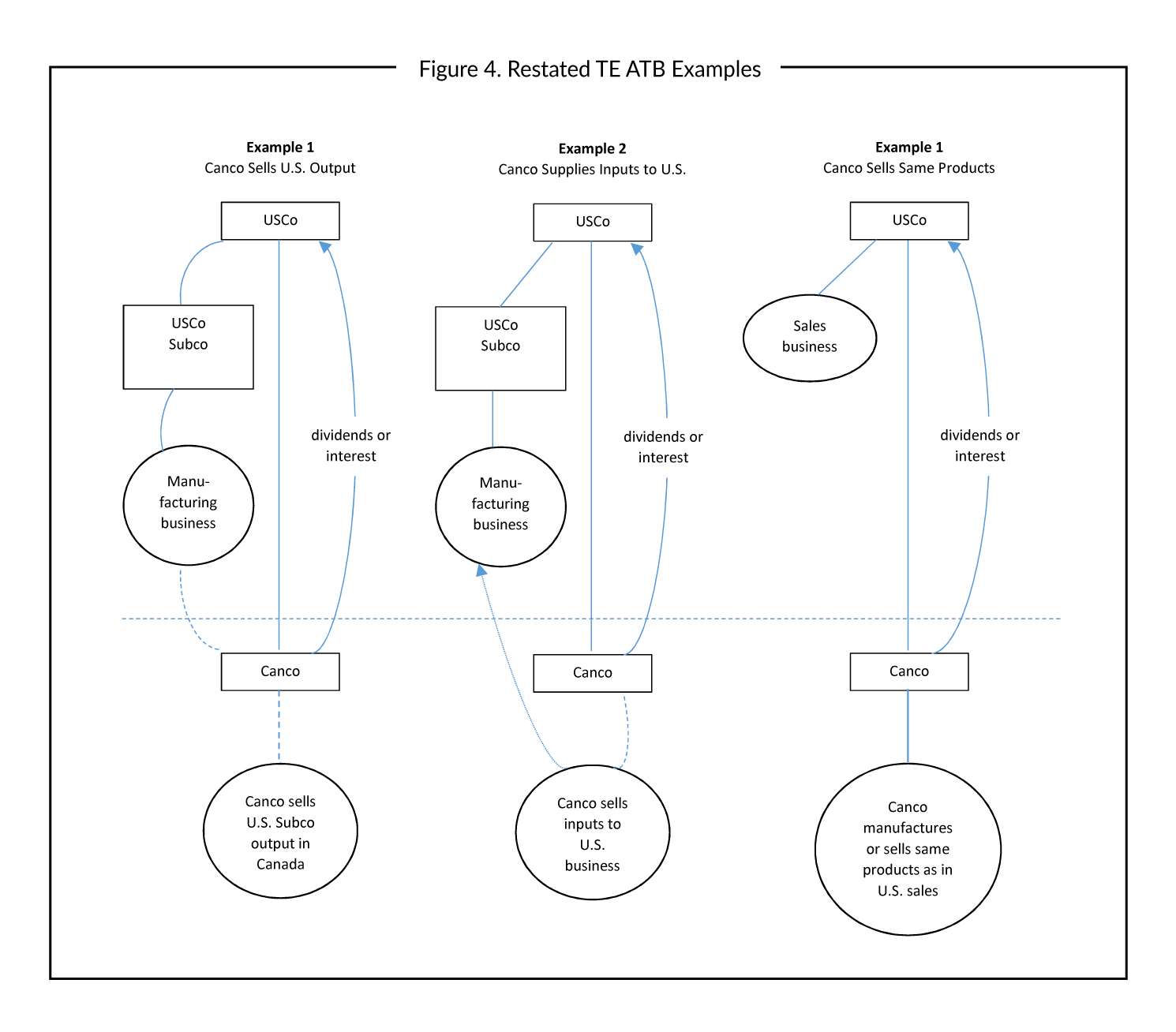

- Paragraph 3: an “active trade or business” (ATB) exception, allowing a non-qualifying person who is a resident of one of the two countries and engaged in the active conduct of a substantial trade or business in that country to claim treaty benefits with respect to items of income derived from the other country in connection with or incidental to that home-country trade or business.

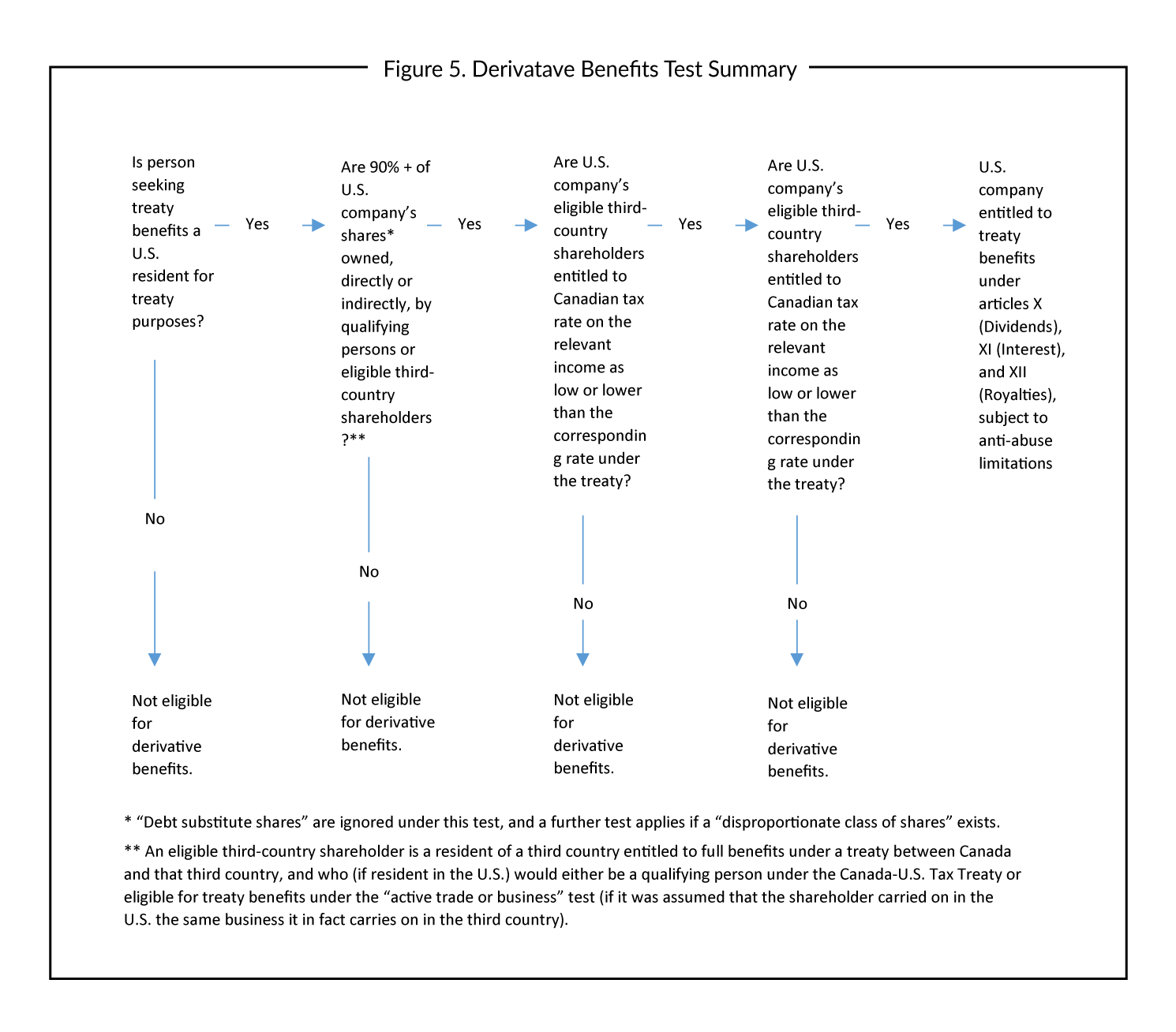

- Paragraph 4: a “derivative benefits” exception, allowing a company that is resident in one of the two countries to claim treaty benefits under articles X (Dividends), XI (Interest), and XII (Royalties) if 90% or more of the company’s shares (by votes and value) are held (directly or indirectly) by persons who are either qualifying persons or residents of countries with which the other country has a tax treaty providing benefits for the relevant item of income as good or better than those provided for under the treaty. 35 This exception is the subject of a base erosion anti-avoidance rule directed at expenses payable by the company to persons who are not qualifying persons.

- Paragraph 6: a residual exception, allowing a person that is a resident of one of the two countries and is not otherwise entitled to treaty benefits under the LOB rules to claim treaty benefits, when the competent authority of the other state determines that either:

- the person’s creation and existence did not have as a principal purpose the obtaining of treaty benefits not otherwise available; or

- it would be inappropriate to deny treaty benefits to that person.

- Paragraph 7: a residual clause stating that nothing in the LOB article will be construed as restricting a country’s right to deny treaty benefits when it can reasonably be concluded that doing otherwise would result in an abuse of treaty provisions.

Figure 1 summarizes the analysis from the perspective of a U.S. resident seeking treaty benefits from Canada.