Exit from Canada

1. Taxation of Capital Gains

- Non-residents of Canada are generally subject to Canadian tax on capital gains only where (1) the property they dispose of is “taxable Canadian property” (“TCP”), and (2) they are not entitled to relief under an applicable tax treaty

- Amounts received by a non-resident seller in respect of “restrictive covenants” may be subject to Part XIII withholding tax (25%, subject to possible reduction under an applicable tax treaty)

- Earn-out payments received by a seller can be taxed quite adversely unless structured to come within one of two possible exceptions

- Tax treaties are often an important source of relief for non-residents realizing capital gains on taxable Canadian property, although the Capital Gains articles of Canada’s tax treaties vary widely in terms of the relief offered, and in most treaties (not the U.S.) the new “principal purpose test” created under the OECD Multilateral Instrument (which Canada has adopted and ratified) will restrict claims for relief

- Was the property “taxable Canadian property” (TCP) under the ITA?

- Was there a gain on the property (viz., did the non-resident’s proceeds of disposition exceed the sum of their cost of the property for Canadian tax purposes plus any costs of disposition), or any other form of income recognition such as recaptured capital cost allowance on depreciable property?

- Can the non-resident can claim relief from Canadian taxation under an applicable tax treaty (if any) between Canada and the non-resident’s home country?

- Does the non-resident have realized losses or other Canadian tax attributes that can be used to offset any taxable gains or income realized on the disposition?

When a partnership interest is disposed of, the normal rule including only 50% of any capital gain in the seller’s income does not apply if the buyer is (directly or through a partnership or trust) a tax-exempt or non-resident (s. 100(1)). This highly punitive rule looks beyond the immediate buyer at the time of sale, and may also apply if a tax-exempt or a non-resident (directly or through a partnership or trust) acquires the partnership interest being disposed of as part of the same “series of transactions” that includes the immediate sale. The term “series of transactions” has been defined broadly by Canadian courts, leading to considerable uncertainty as to how much of a connection need exist between the buyer’s purchase of the partnership interest from the seller and what the buyer ultimately does with it. The result is that the seller will typically demand some comfort from the buyer that the buyer will not re-sell the partnership interest to such an entity as part of the same “series of transactions” that includes the immediate purchase and sale.

The Income Tax Act

The first step is to determine whether Canadian domestic law taxes amounts received by a non-resident from the sale of whatever property directly or indirectly constitutes the non-resident’s Canadian investment or business (e.g., a share of a corporation).

Taxable Canadian Property

Canada taxes non-residents of Canada on gains from the disposition of capital property only if such property is “taxable Canadian property,” (“TCP”) which essentially consists of:

- real or immovable property situated in Canada (which for most relevant purposes includes interests in Canadian mining and oil and gas properties and rights to cut timber in Canada);

- most property used in a business carried on in Canada;

- a share of the capital stock of a corporation that is listed on a designated stock exchange 1 Designated stock exchanges in Canada include the Toronto Stock Exchange, the TSX Venture Exchange (Tiers 1 and 2), and the Montreal Exchange. Many foreign stock exchanges are also designated, including the New York Stock Exchange and the London Stock Exchange. The Department of Finance maintains a list of stock exchanges that have been designated, available at https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/services/designated-stock-exchanges.html . at the particular time, if at any time during the previous 60 months both:

- 25% or more of any class of the corporation’s shares were owned by the non-resident vendor, persons not dealing at arm’s length with that vendor, or a combination of the vendor and such persons; and

- more than 50% of the fair market value of the share was derived directly or indirectly from Canadian real property (that is, an interest in land situated in Canada, an interest or royalty in a mine or oil field located in Canada, a right to remove timber on Canadian property, or options or interests regarding any of the foregoing); 2 Both tests must be met at the same time in order for a share to fall within this branch of the definition. This same two-part test also applies to determine the TCP status of a share of a mutual fund corporation or a unit of a mutual fund trust.

- a share of the capital stock of a corporation (excluding a mutual fund corporation) that is not listed on a designated stock exchange at the particular time, if at any time during the previous 60 months more than 50% of the fair market value of the share was derived directly or indirectly 3 Except if so derived through a corporation, partnership, or trust, the shares or interests in which were not themselves TCP. This exception is meant to prevent anomalous and unintended results such as might occur (for example) if a non-resident owning less than 25% of the listed shares of a public company interposed a private holding corporation (that is, the shares of which are not listed on a designated stock exchange) to hold those public company shares. For further discussion, see here Canadian real property (that is, an interest in land situated in Canada, an interest or royalty in a mine or oil field located in Canada, a right to remove timber on Canadian property, or options or interests regarding any of the foregoing);

- an interest in a partnership or an interest in a trust (other than a unit of a mutual fund trust or an income interest in a trust resident in Canada) if at any time during the previous 60 months more than 50% of the fair market value of the interest was derived directly or indirectly 4 Id. from Canadian real property (that is, an interest in land situated in Canada, an interest or royalty in a mine or oil field located in Canada, a right to remove timber on Canadian property, or options or interests regarding any of the foregoing); and

- an interest, option, or right regarding any of the foregoing property, whether or not the property exists.

Note that with regard to shares of a corporation, the TCP definition does not distinguish between Canadian and foreign corporations. As such, shares of a foreign corporation will constitute TCP if the corporation owns enough Canadian real property (directly or indirectly), notwithstanding the practical enforcement issues associated with trying to tax such foreign shares.

In addition, the ITA deems property to be TCP where the property in question was acquired in exchange for other property that was itself TCP in most tax-deferred transactions (i.e., a tax-deferred share-for-share exchange. For example, shares (or a partnership interest) acquired in exchange for TCP disposed of in most tax-deferred transfers is generally deemed to be TCP by the applicable ITA rollover provision whether or not the new shares (or partnership interest) would otherwise fall within the TCP definition. For example, when a non-resident transfers TCP to a Canadian corporation in exchange for shares of that Canadian corporation under s. 85(1), such shares are deemed to be TCP of the non-resident for the 60-month period following the exchange.

Table 1. Summary of TCP Status

|

Property |

TCP Status |

|---|---|

|

Shares of corporations listed on a designated stock exchange; shares of mutual fund corporations; units of mutual fund trusts. |

TCP if at any time during the preceding 60 months, both:

|

|

Unlisted shares of corporations (other than mutual fund corporations); interests in partnerships and most trusts. |

TCP if at any time during the preceding 60 months more than 50% of value of the share or interest was derived from Canadian real property directly or indirectly (other than through a corporation, partnership, or trust the shares or interests of which are not themselves TCP at that time). |

The ITA does not provide any specific rules on when shares will be considered to have derived their value primarily from Canadian real property. There are a number of interpretational issues arising from this rule, such as:

- the practical difficulty of showing that that no time during a 5-year period did the share derive its value primarily from Canadian real property;

- how to handle debts and other liabilities, both to external creditors and within a corporate group; and

- the manner in which a corporation that owns interests in other entities (e.g., shares of a subsidiary) may be considered to indirectly derive some of its value from any Canadian real property owned by those other entities.

Since shares are by nature a residual entitlement (i.e., creditors are entitled to a corporation’s assets ahead of shareholders, who share in whatever assets are left after the corporation’s debts have been paid), one might have thought that the test should apply on a “net asset” basis, i.e., after deducting the corporation’s debts. However, the CRA interprets this test on a gross assets basis ignoring the company’s liabilities, ostensibly on the basis that this is consistent with the Commentary on Article 13 of the OECD Model Tax Convention. 5 From a practical perspective it is likely that the CRA is concerned with the potential for taxpayer planning opportunities that exist if debts are netted against assets. The CRA has expressed its views on this and similar issues in CRA document 2015-0624511I7, dated May 1, 2017.

While it is always useful to be aware of how the CRA administers the law, it is important to understand that none of these CRA positions have yet been tested in court and they are not the law. 6 See also CRA document 2016-0668041E5, dated 22 September, 2017. In fact, the CRA’s insistence on using a “gross assets” test constitutes a reversal from its earlier administrative policy expressed in a 2003 technical interpretation, 7 CRA document 2003-0029675, dated Sept. 5, 2003. in which the CRA:

- stated “we feel that one can use the gross asset value method, the net asset value method or any other valuation method that is appropriate in the circumstances”; and

- adopted a position from a 1984 Round Table in which the CRA stated that it would accept a valuation method that “assigns debt to the assets to which the debt reasonably relates” unless there is evidence of manipulation in contemplation of a share sale. 8 Revenue Canada Round Table, Report of Proceedings of Thirty-Sixth Tax Conference, 1984 Tax Conference (Toronto: Canadian Tax Foundation, 1985), Question 58 at p. 824.

Restrictive Covenants

When selling their Canadian investment, non-residents should be mindful of a broadly-worded rule imposing 25% Part XIII withholding tax on payments made in respect of “restrictive covenants.” Restrictive covenants are defined as an agreement, undertaking or waiver (whether or not legally enforceable) intended to affect the acquisition of property or services.

The original motivation behind these rules were sales structured to direct significant portions of the sale consideration to specific individuals as payments made for covenants not to compete with buyers, which the courts determined were tax-free. However, the legislative response to this perceived mischief goes significantly beyond non-competition payments. 9 This provision was recently applied to a non-resident seller who received a separate payment from another shareholder for entering into a share purchase agreement with a buyer: see Michael Kandev and James Trougakos, “Obscure Canadian Withholding Tax Rule a Trap for the Unwary”, Tax Notes International, March 9, 2020, p. 1091. These rules are especially negative for non-resident sellers, because when they apply, they have the effect of recharacterizing capital gains (which are often untaxed in Canada for non-residents) into payments that are subject to withholding taxes.

There are two basic elements to these rules:

- Rule 1 – Deemed Income Treatment. If an amount is receivable in exchange for granting a restrictive covenant, that amount is deemed income to the recipient, unless one of three specific exceptions for certain arm’s-length transactions applies to allow a different result. 10 The most relevant exception is one applicable to a non-competition covenant given on a sale of shares when the grantor deals at arm’s length with the buyer and the parties file a joint election under paragraph 56.4(3)(c), in which case the amount receivable for the restrictive covenant is simply added to the grantor’s proceeds of disposition from the share sale.

- Rule 2 – Deemed Reallocation. If the CRA establishes that the amount allocated by the parties to the restrictive covenant is unreasonably low, another rule allows an amount receivable for something else (e.g., share sale proceeds) to be deemed receivable for the restrictive covenant, such that Rule 1 applies. This deemed reallocation rule is excluded for non-competition covenants (only) if any of three exceptions apply.

Receiving an amount as fully taxable income is generally the worst possible result for the person granting the restrictive covenant, while buyers are largely indifferent (but would generally prefer payments that carry no withholding tax obligation for them). The parties to an arm’s-length sale of shares or a business typically deal with Rule 1 by:

- allocating a nominal amount such as $1 11 Commercial lawyers frequently allocate $1 as discrete consideration for granting the restrictive covenant to ensure that the covenant is not unenforceable for lack of consideration under Canadian contract law. to the restrictive covenant; and

- if possible, trying to come within one of the three exceptions for arm’s-length transactions in case the CRA tries to allocate some higher amount to the restrictive covenant under Rule 2.

The CRA rarely challenges amounts allocated to restrictive covenants by arm’s-length parties under Rule 2, given the high standard the caselaw establishes applying the reallocation rules in section 68. 12 See TransAlta Corp. v. The Queen, 2012 FCA 20, citing the Exchequer Court’s statement in Gabco Ltd. v. Minister of National Revenue, 68 DTC 5210: “It is not a question of the Minister or [this] Court substituting its judgment for what is a reasonable amount to pay, but rather a case of the Minister or the Court coming to the conclusion that no reasonable business man would have contracted to pay such an amount having only the business consideration of the appellant in mind.”

Non-competition covenants are common in commercial sales, and receive advantageous treatment under both the share sale exception to Rule 1 and the three exceptions to Rule 2. All three exceptions require that the grantor of the non-competition covenant deal at arm’s length with the buyer, and receive no proceeds for granting the non-competition covenant. 13 The CRA will accept allocating consideration of $1 to a non-competition covenant to ensure contractual enforceability as “no proceeds”: see CRA document 2014- 0547251C6, dated Dec. 2, 2014. When drafting a sale agreement, the parties usually try to come within one of the three exceptions to Rule 2 (including agreeing to make any required elections), and should try and integrate any undertakings related to or similar to the non-competition undertaking (e.g., a non-solicitation covenant) into the non-competition clause. 14 The CRA has stated that a non-competition covenant may be considered to include a related undertaking (such as a non-solicitation covenant) that is ‘‘an integral component of the covenant not to compete”: CRA document 2013-0495691C6 (Oct. 11, 2013).

Earn-outs

Sales of shares or a business frequently use “earn-outs” as a way of agreeing on the purchase price, whereby a portion of what the seller receives is computed based on post-closing profits or revenues. Such an arrangement (an earn-out) can help bridge valuation differences between the parties, but must be approached carefully from a Canadian tax perspective. This is because s. 12(1)(g) provides that payments based on the use of or production from property, including as an installment of the sale price, are treated as income, not capital gains, to the recipient. Thus, unless an exception (discussed below) applies, an earn-out payment can be very negative for a seller from a Canadian tax perspective if s. 12(1)(g) applies:

- an earn-out treated as regular income is effectively taxed as twice the rate applicable to a capital gain (since only 50% of capital gains are included in income);

- an earn-out treated as income results in a taxable receipt that is not reduced or absorbed by the seller’s adjusted cost base of the disposed-of property;

- the seller cannot apply any available capital losses against the earn-out; and

- in the case of a non-resident seller, the application of s. 12(1)(g)’s Part XIII counterpart in s. 212(1)(d)(v) creates a payment to which 25% Part XIII withholding tax applies, instead of a capital gain that in many cases is not subject to tax in Canada (either because the disposed-of property is not “taxable Canadian property” or because of relief under a tax treaty).

Note that s. 12(1)(g) does not apply where the timing of the payments to the seller is variable but the amount is fixed.

Because the income characterization of the earn-out payment under s. 12(1)(g) is one-sided (i.e., only applicable to the seller, not the buyer), the buyer is typically indifferent from a tax perspective as to how the earn-out is structured. However, if the seller is a non-resident, a buyer will have a Part XIII withholding obligation on earn-out payments to the non-resident seller, and so may be motivated to assist the seller in trying to come within one of the two exceptions to s. 12(1)(g) and its Part XIII equivalent.

There are two exceptions possible for keeping the economics of an earn-out while avoiding the adverse tax treatment under s. 12(1)(g). Under the “cost recovery method” described in CRA Interpretation Bulletin IT-426R, a seller of shares (not other property) can avoid section 12(1)(g) and reduce the cost basis in its shares as amounts of the sale price become determinable, i.e., receipts are applied first against cost basis. The result is that no capital gain is realized until the amount of the sale price that can be calculated with certainty and to which the seller has an absolute (although not necessarily immediate) right exceeds the seller’s cost base. The administrative policy applies if the following conditions are met:

- the seller deals at arm’s length with the buyer;

- the earn-out feature relates to underlying goodwill whose value cannot reasonably be expected to be agreed on by the parties at the date of sale;

- the last contingent amount under the earn-out becomes payable within five years of the end of the target corporation’s tax year that includes the date of sale; and

- the seller submits a formal request to use the cost recovery method with its year-of-sale tax return. 15 See Interpretation Bulletin IT-426R, ‘‘Shares Sold Pursuant to an Earn Out Agreement’’ (Sept. 28, 2004).

While IT-426R refers to Canadian resident sellers only, the CRA has subsequently stated that non-resident sellers who would otherwise be eligible to use the cost recovery method will generally not be subject to the Part XIII withholding tax equivalent of section 12(1)(g). 16 See CRA documents 2019-0824461C6, dated Dec. 3, 2019, and 2006-0196211C6, dated Oct. 6, 2006. The CRA has a number of important administrative positions concerning the cost recovery method:

- it may be used on the sale of shares of a holding company whose only assets are shares of another corporation; 17 CRA document 2019-0824531C6, dated Dec. 3, 2019.

- once a seller has chosen to use a different method to calculate its proceeds of disposition, it may not thereafter change its mind and file amended tax returns applying the cost recovery method; 18 CRA document 2014- 0529221E5, dated Aug. 27, 2014. and

- the capital gains reserve for deferred sale proceeds cannot be claimed on an earn-out or reverse earn-out. 19 CRA document 2013-0505391E5, dated Feb. 24, 2014.

The more commonly used exception is a “reverse earn-out,” described in CRA Interpretation Bulletin IT-462. 20 While Interpretation Bulletin IT-462 (Oct. 27, 1980) has been archived, it remains valid CRA administrative policy, including on dispositions of property other than shares (see CRA document 2011-0423771E5, dated Dec. 20, 2011), and the CRA has issued favorable advance tax rulings on them (see for example CRA document 2009-0337651R3, dated Sept. 9, 2009). The non-applicability of s. 12(1)(g) to reverse earn-outs is supported by Pacific Pine Co. Ltd. v. M.N.R., 61 DTC 95 (TAB). Under a reverse earn-out, the purchase price is expressed as a maximum, and is reduced if reasonable conditions specified by the parties regarding future earnings are not met. Under a reverse earn-out, both the seller’s proceeds of disposition and buyer’s cost basis in the year of sale will be treated as the maximum amount owing (even though the entire amount is not paid in that year), subject to appropriate adjustment (reduction) in post-sale tax years if the relevant conditions are not met and the sale price is therefore reduced. Buyers are typically willing to accommodate sellers in structuring sales as reverse earn-outs, although it can be troublesome for a buyer to deal with post-closing adjustments (i.e., reductions) to the buyer’s cost basis because some earn-outs conditions are not met if the buyer sells the purchased shares before the end of the earn-out period.

Because the consequences of an improperly structured earn-out are quite negative, it is important for sellers (and buyers making earn-out payments to non-resident sellers) to obtain legal advice on the correct structuring.

Tax Treaties & Capital Gains

Where a non-resident seller of taxable Canadian property has realizes a capital gain and is resident in a country that has a tax treaty with Canada, it is important to consider whether that treaty prevents Canada from taxing the gain. Relief from Canadian capital gains tax on dispositions of shares or partnership interests varies widely amongst Canada’s tax treaties. In some cases no relief is offered, while in most cases Canada is permitted to tax the gain only where the share derives its value primarily from Canadian real property. In some cases, the treaty excludes from “Canadian real property” for this purpose real property that is used in the corporation or partnership’s business, greatly reducing Canada’s right to tax. A number of treaties also restrict Canada’s right to tax shares that are publicly listed and/or which fall below a prescribed percentage of share ownership. A few treaties (including the Canada-U.S. Tax Treaty) also limit Canada’s right to tax capital gains on shares to shares of corporations that are Canadian residents.

Table 1 summarizes the capital gains articles of Canada’s tax treaties. Note that the Income Tax Conventions Interpretation Act (which contains a number of important rules on how Canada interprets and applies its tax treaties) should be reviewed whenever treaty relief from Canadian tax is being considered.

Table 2. Canadian Tax on Capital Gains from Shares – Tax Treaties

|

Canada May Tax Share Sale Gains |

Countries |

|---|---|

|

All (no residual allocation of taxing rights to country of residence) |

Argentina, Australia,* Brazil,* Cameroon, Chile, China,* Egypt, Guyana,X India, Japan, Jordan, New Zealand, Nigeria, Papua New Guinea, Trinidad & Tobago, Vietnam |

|

Shares deriving their value primarily from Canadian real property |

Algeria, Barbados, Colombia,1RP# Gabon, Hong Kong, Indonesia,RP Ireland, Israel, Korea,RP# Madagascar,X* Poland, Portugal, Senegal, Serbia,1 Taiwan,X Turkey,@ United Arab Emirates, United StatesRPX |

|

Shares deriving their value primarily from Canadian real property (excluding non-rental real property used in issuer company’s business) |

Armenia, Austria,P Azerbaijan,1 Belgium,R BulgariaR Croatia, Czech Republic,P Denmark,R Ecuador,X Estonia,RP Germany,RPX* Greece,P Hungary,RP Iceland, Italy, Kazakhstan,P Kyrgyzstan,RPX Latvia,RP Lithuania,RP Luxembourg, Mexico,1R# Moldova, Mongolia, Namibia,X* Netherlands,RP* Norway, Oman, Peru, Romania, Russia,RP Slovakia, Slovenia, South Africa,RP Sweden,RP Switzerland,RPX* Tanzania,RP Ukraine,RP United Kingdom,P Uzbekistan,PX VenezuelaX |

|

Shares of company whose property consists primarily of Canadian real property |

Bangladesh, Cyprus, Dominican Republic,^ Finland,1B France,1B Ivory Coast, Jamaica,^ Kenya, Kuwait,B Malaysia,^* Malta,B Morocco,^ Pakistan,^RP# Philippines,^ Singapore,^ Spain,B Thailand, Tunisia, Zambia |

Italics: Exemption for exchange-listed shares.

Underlining: size of share ownership in issuer company relevant.

1 Rules refer to other interests in issuer company beyond shares.

@ Canada may also tax gains realized within one year.

#: Canada may tax a resident of Colombia, Korea, Mexico, Pakistan or Sri Lanka on gains from shares that are part of a substantial interest in Canadian-resident company irrespective of what they derive their value from.

R Fiscal residence of issuer company relevant.

* Treaty under renegotiation or signed but not yet in force.

X Canada has not included as a covered tax agreement for MLI purposes.

P Rule for partnerships interests different from for shares of companies.

Canada’s right to tax share gains of a Zimbabwean resident is limited to shares of Canadian-resident companies.

Under most Canadian tax treaties, the Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (MLI) will affect capital gains taxation by (1) adding a 365-day lookback rule when testing whether shares and other interests derive their value primarily from (or whether an entity’s property consists primarily of) Canadian real property, and (2) imposing a “principal purpose test” to limit entitlement to treaty benefits. The MLI’s impact on Canada’s right to tax treaty residents on capital gains is discussed in detail here. As more of Canada’s tax treaty partners ratify the MLI, it will have an increasingly greater impact on Canada’s right to tax capital gains, in particular as regards the principal purpose test is establishes in order to claim treaty benefits.

2. s. 116 ITA Compliance

- In order to support the CRA’s ability to actually collect tax owing by non-resident sellers of taxable Canadian property, s. 116 creates a variety of rules (the s. 116 system) applicable to such non-resident sellers and those buying property from them

- Most importantly, s. 116 imposes a withholding and remittance obligation on the purchaser of taxable Canadian property from a non-resident, obligating the purchaser to withhold 25% (or 50% in some cases) of the purchase price and remit it to the CRA, generally whether or not the seller has a gain or is subject to Canadian tax on the sale

- A purchaser who fails to withhold and remit as required under s. 116 is itself liable for the amount that should have been withheld (plus interest and penalties), with no time limit for the CRA to assess such amounts

- A non-resident vendor can apply to the CRA for a “certificate of compliance”, which relieves the purchaser of the obligation of withhold and remit (to the extent specified in the certificate), and requires the vendor to satisfy the CRA that no tax is owing or make arrangements to pay any tax owing

- the s. 116 system also imposes on the seller an obligation to notify the CRA of the sale and to file a Canadian income tax return

- the s. 116 system is described in detail in Steve Suarez and Marie-Eve Gosselin, “Canada’s Section 116 System for Non-resident Vendors of Taxable Canadian Property,” Tax Notes International,” April 9, 2012, p. 175.

- Vendor Notification. The non-resident vendor may be required to notify the CRA of the disposition.

- Purchaser Remittance. The purchaser of the property, whether Canadian or non-Canadian, may be required to remit a specified percentage of the purchase price (usually 25%) to the CRA. Such remittance is credited toward the vendor’s Canadian tax liability (if any).

- Vendor Tax Return Filing. The vendor may be obligated to file a Canadian income tax return for the tax year in which the disposition occurred.

Non-resident sellers of property with a Canadian connection should expect to see buyers raise the issue of s. 116 compliance and be prepared to address it in the course of negotiations. If the seller plans to obtain a certificate of compliance, this process should be started as early as possible, as it can take some months to complete, depending on the facts.

Table 3. Summary of the 116 System

|

Vendor Notification |

Purchaser Remittance |

Vendor Tax Return Filing |

|---|---|---|

|

Potentially applicable when non resident disposes of TCP. |

Potentially applicable when TCP is acquired from non-resident. |

Potentially applicable where non-resident disposes of TCP. |

|

Not applicable on dispositions of excluded property (for example, publicly listed shares), but for transfers of treaty-exempt property between related parties purchaser must file notice with CRA if vendor does not. Notice not required on dispositions of section 116(5.2) property. |

Not applicable (1) on acquisitions of excluded property; (2) if purchaser reasonably believes vendor is a Canadian resident after making reasonable inquiry; or (3) if vendor obtains certificate of compliance from CRA. Exception also provided for treaty-protected property if necessary conditions met. |

May not apply if all TCP dispositions are excluded dispositions and vendor has no outstanding tax liability. |

|

May apply even if no gain is realized or no tax is payable on the disposition. |

Remittance obligation is generally 25 percent of sale price, whether or not vendor realizes any gain or owes tax. |

Always applicable where Part I income tax is owing for the year by vendor. |

|

Required if obtaining a certificate of compliance to address purchaser remittance obligation. |

Arm’s-length purchasers will often insist on certificate of compliance unless there is no material risk, failing which they will withhold required funds from sale proceeds. |

Vendor will want to file a tax return and claim a refund if amount remitted by purchaser exceeds vendor’s tax owing. |

|

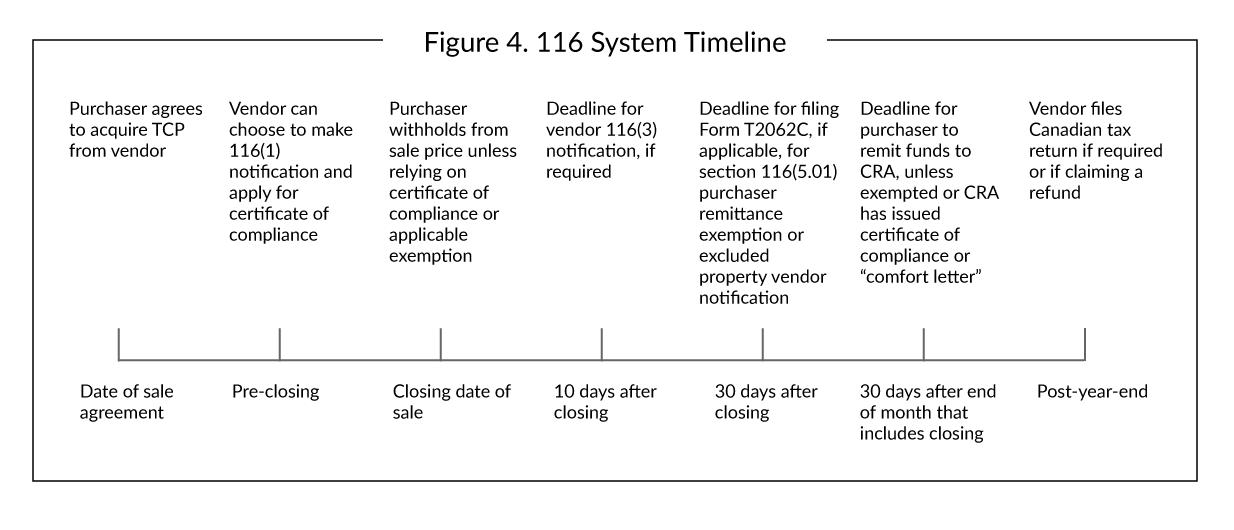

Notification deadline is 10 days after disposition. |

CRA comfort letter may suspend remittance due date where vendor has applied for certificate of compliance. |

|

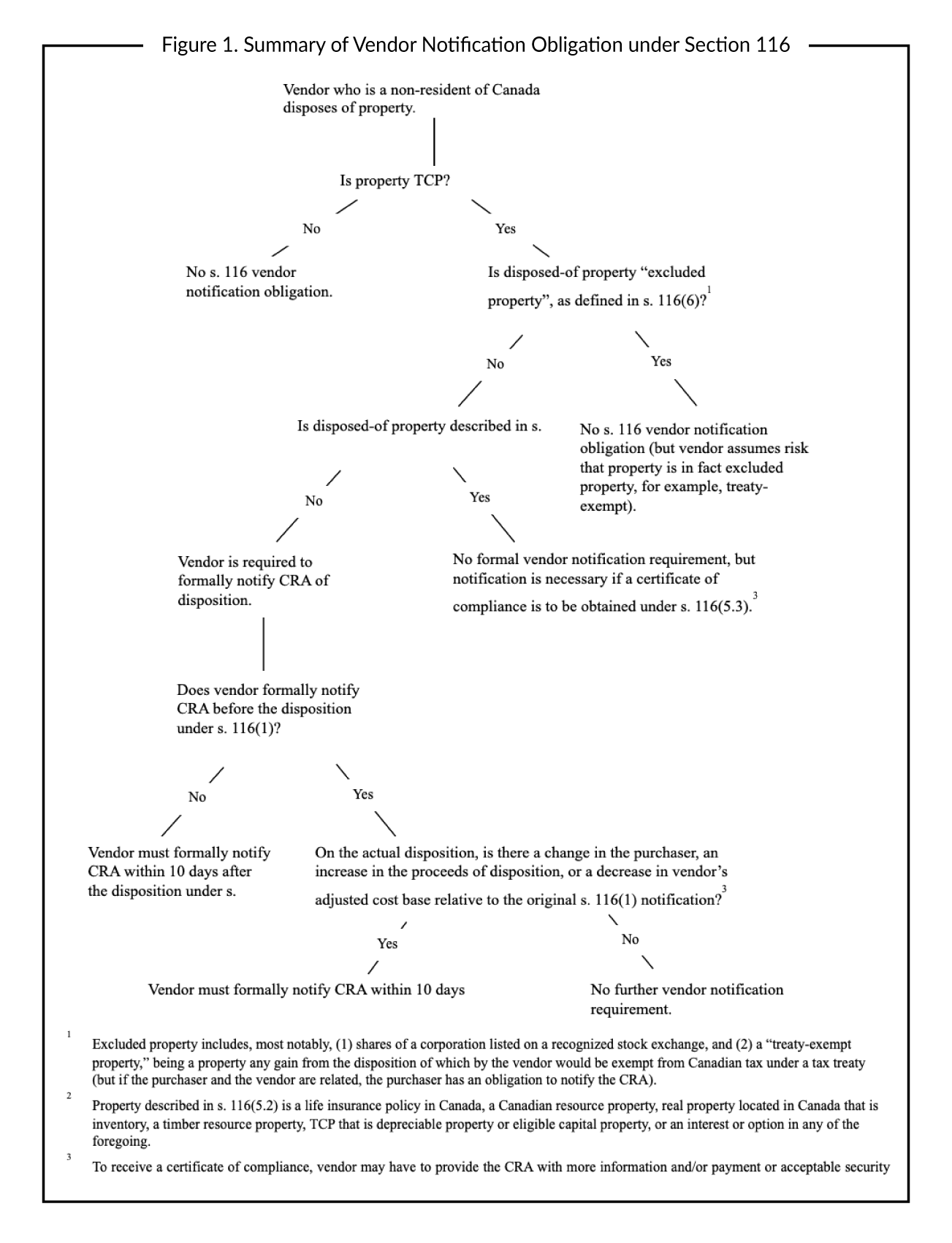

Vendor Notification

The vendor notification requirement under s. 116 (summarized in Figure 1) is triggered on most dispositions of TCP, and requires the seller to provide the CRA with information about the disposition within a prescribed time frame (ss. 116(1) and (3)). A “disposition” is a sale or other alienation of a property, including one that is tax-deferred such as under subsection 85(1). 21 The term “disposition” is defined in the ITA as including any transaction entitling a taxpayer to proceeds of disposition of the property, and includes a redemption, acquisition, repurchase, or cancellation of shares by a corporation. Administratively, the CRA takes the position that a shareholder of a corporation that is a party to an amalgamation (a form of tax-deferred merger) of two or more corporations need not notify the CRA when the old shares were TCP and the new shares are deemed to be TCP by s. 87(4); see Income Tax Folio S4-F7-C1, “Amalgamations of Canadian Corporations,” at para. 1.82 Some vendors who are not subject to the formal vendor notification obligation voluntarily choose to provide notification of a disposition, as part of the process of dealing with the purchaser’s remittance obligation by obtaining a certificate of compliance (discussed below).

No vendor notification requirement applies to property described in s. 116(5.2) (“116(5.2) property”). Such property constitutes an assortment of special types of property the disposition of which may give rise to regular income rather than (or in addition to) capital gains. 22 116(5.2) property comprises a life insurance policy in Canada, a Canadian resource property, Canadian real property that is held as inventory or otherwise not as capital property, a timber resource property, depreciable property that is TCP, or any interest or option regarding the foregoing. Such property is not exempted from the 116 system, but is subject to a modified set of requirements.

Excluded Property

A disposition of “excluded property” (s. 116(6)) does not create a vendor notification obligation. Excluded property is typically TCP that is impractical to make subject to the purchaser remittance and vendor notification obligations (such as most publicly listed securities) or property that the purchaser cannot reasonably be expected to know is TCP. For instance, “excluded property” includes property that is TCP solely because it has been deemed to be TCP under one of the deeming rules applicable to tax-deferred transfers described earlier.

The most important kind of excluded property is shares of a corporation that are listed on a “recognized stock exchange.” A recognized stock exchange includes a designated stock exchange (described in Section 1 Taxation of Capital Gains, The Income Tax Act subsection, Taxable Canadian Property) or any other stock exchange located in Canada or in an OECD member country that has a tax treaty with Canada. 23 Definition of the term “recognized stock exchange” in s. 248(1). A list of Canada’s tax treaties can be found on the Department of Finance website at http://www.fin.gc.ca/treaties-conventions/treatystatus_-eng.asp. Units of mutual fund trusts are also excluded property, as are bonds, debentures, mortgages, and similar obligations. Publicly-traded partnership units and publicly traded trust units that are not mutual fund trust units are not excluded property. Inventory (other than Canadian real property) of a business carried on in Canada is also excluded property. An option or interest in excluded property is itself excluded property.

Also excluded property is “treaty-exempt property,” (s. 116(6.1), defined as “property any income or gain from the disposition of which by the taxpayer at that time would, because of a tax treaty with another country, be exempt from tax under Part I.” However, when the vendor and the purchaser are “related,” 24 “Relatedness” is defined in the ITA; very generally, persons may be “related” by virtue of blood relationship (parent and child), marriage, or legal control (when one corporation has de jure control of another). In some cases rights under an agreement of purchase and sale for a controlling interest in a corporation may cause an otherwise unrelated purchaser and vendor to be deemed to be related. in order for the property to be treaty-exempt property the purchaser must also provide notice to the CRA within 30 days after the acquisition setting out:

- the date of the acquisition;

- the name and address of the vendor;

- a description of the property sufficient to identify it;

- the amount paid or payable for the property; 25 When the amount paid or payable for the property includes a contingent or variable component (such as a post-closing adjustment based on net working capital) that is not known until after the filing due date for the purchaser’s Form T2062C, the CRA has stated that a purchaser who has filed the required notice on time will have complied with its obligations if the purchase price shown includes a portion that has been estimated, indicating such on the notice. However, if the final amount turns out to be different from the amount reported, the purchaser should promptly provide a revised notice to the CRA; see CRA document 2009-0347711C6, dated Dec. 8, 2009. and

- the country whose Canadian tax treaty the non-resident is relying on to exempt the gain from Canadian taxation.

This information is largely the same as that required under the vendor notification obligation. As such, for related parties dealing with treaty-exempt property, in most cases the “treaty-exempt property” component of “excluded property” essentially just gives the parties a choice of having the purchaser or the vendor notify the CRA of the disposition. The purchaser may satisfy this related-party notice requirement by completing and submitting Form T2062C or otherwise providing this information to the CRA.

A vendor relying on the treaty-exempt property element of the excluded property definition to justify not complying with the vendor notification obligation assumes the risk that the property is not treaty-exempt. In particular, U.S. vendors relying on the definition of treaty-exempt property must be sure that they are entitled to treaty benefits under the limitation on benefits provisions of the Canada U.S. Income Tax Treaty. A vendor related to the purchaser must also rely on the purchaser to provide the CRA with the requisite notification on time.

The CRA does not accept late-filed notifications, meaning that the property will not be considered to be “excluded property”: see Information Circular IC 72-17R6, “Procedures concerning the disposition of taxable Canadian property by non-residents of Canada – section 116,” para. 28. If the Form T2062C used to make the notification has been late-filed, the CRA has stated that it will notify a taxpayer so that it is aware that the notification is invalid. Otherwise, while the CRA will not generally acknowledge receipt of a Form T2062C.

Procedures and Penalties

A vendor can meet the vendor notification requirement in two ways. Under the first, referred to as a 116(3) notification, the vendor simply waits until the disposition occurs and then within 10 days following sends the CRA the following information:

- the name and address of the purchaser;

- a description of the property sufficient to identify it;

- the amount of the proceeds of disposition received or receivable by the vendor; and

- the adjusted cost base of the property (ACB, or cost for tax purposes) to the vendor immediately before the disposition.

A 116(3) notification has the advantage of requiring only one filing, but because it is made post-disposition it leaves very little time to obtain a certificate of compliance, which can adversely affect the vendor in dealing with the purchaser remittance obligation.

The more commonly used procedure is a 116(1) notification, in which the vendor provides notification to the CRA before the disposition. A 116(1) notification requires the vendor to submit to the CRA information similar to the information in a 116(3) notification, except that the amount shown as the proceeds of disposition is an estimate and the vendor’s ACB of the property is determined at the time of notification. Notification is made using Form T2026.

If a 116(1) notification was provided to the CRA, a 116(3) notification must also be filed only if there has been a change in the material information in the s. 116(1) notification (i.e., the proceeds of disposition, the vendor’s ACB or the identity of the purchaser). In such case, a 116(3) notification must be made within 10 days after the disposition; otherwise, no further notification is necessary.

On dispositions by partnerships, the CRA’s administratively accepts a single notification of disposition filed by one partner on behalf of all partners, provided that the filing partner gives a complete listing of the non-resident partners that are disposing of the property together with information about those partners in its notification. 26 IC 72-17R6, para. 10. This procedure can be unworkable from a practical perspective, especially for large, widely held partnerships such as private equity funds or other look through entities, or when the partnership has one or more other partnerships as partners.

Failure to make the required notification is an offense under the ITA, subject to a fine of between $1,000 and $25,000, or imprisonment (s. 238(1)). A vendor that does not provide notice when required may also be assessed a penalty of $25 a day for each day the notification is late, subject to a minimum of $100 and a maximum of $2,500 (s. 162(7)).

Certificates of Compliance

A certificate of compliance (often called a “116 certificate”) is closely related to the vendor notification obligation. A vendor applies for a certificate of compliance by providing the information required for vendor notification requirement plus any further information or supporting documentation that the CRA may require, and payment of (or security for payment of) any tax owing. The benefit of a certificate of compliance is that it reduces or eliminates the purchaser’s remittance obligation (discussed below), and so serves as an alternative to the purchaser withholding from the sale proceeds the seller would otherwise receive. Thus, even when the ITA may not formally require vendor notification, it will often be advantageous for the vendor to go through the notification process to obtain a certificate.

The CRA has traditionally said that notification and payment or security should be provided at least 30 days before the property is actually disposed of to permit time to review the transaction and verify that the vendor’s payment or security is adequate. As a practical matter the processing time is often significantly more than 30 days to obtain a certificate of compliance.

When a vendor seeking a certificate of compliance is claiming that Canadian tax owed is reduced or eliminated in reliance on a tax treaty, the information required by the CRA to support the application will be greater than is otherwise the case and the time required for processing will usually be longer. The vendor must identify the applicable provision of the particular treaty and provide documentation to support the claim that the treaty is applicable. Such documentation would include proof of residence or proof that the gain has been or will be reported in the vendor’s country of residence. 27 See the supporting documents list in the instructions to forms T2062, T2062A, or T2062B. The CRA also expects the non-resident to provide a Form NR301, 302 or 303 in support of the request for relief, attesting to various information. 28 The appropriate form to be used depends on the identity of the non-resident: Form NR301 is intended for use by individuals and corporations, Form NR302 should be provided by partnerships, and Form NR303 deals with hybrid entities. See https://www.canada.ca/en/revenue-agency/services/forms-publications/information-on-forms-nr301-nr302-nr303.html .

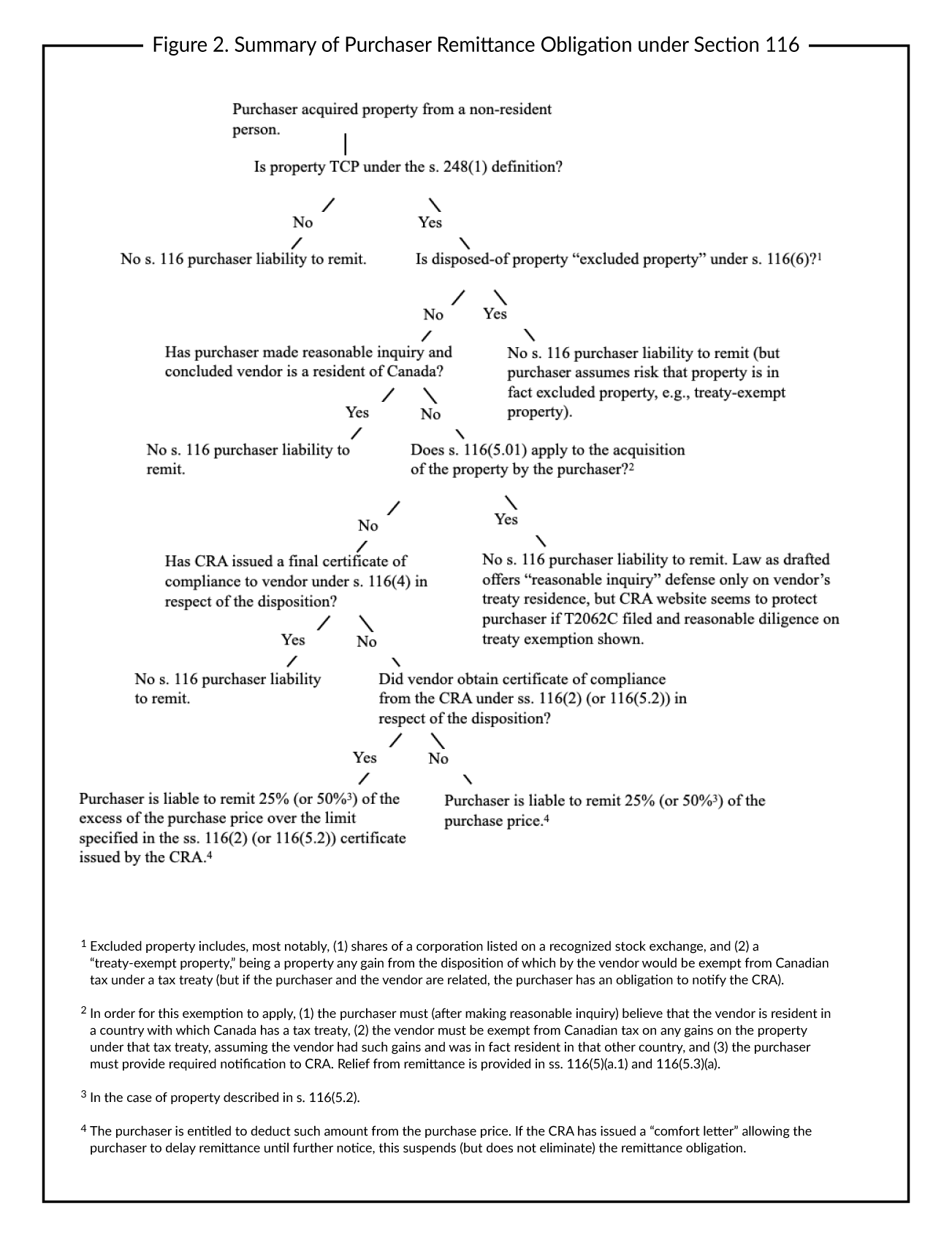

Purchaser Remittance

The 116 system imposes an obligation (often referred to as “s. 116 withholding”) on the purchaser to remit to the CRA a 25% (or in some cases 50%) of the purchase price as a pre-payment of taxes owing by the non-resident, if any, and for this purpose authorizes the purchaser to withhold the necessary amount from the purchase price. This obligation applies whether or not the non-resident has an actual gain on the sale, and in some cases whether or not treaty relief exempts the gain from Canadian tax.

In general terms, a purchaser of TCP from a non-resident vendor essentially has the following options for addressing the purchaser remittance obligation:

- if the property is “excluded property,” the purchaser has no remittance obligation;

- if after making reasonable inquiry the purchaser had no reason to believe that the vendor was a non-resident of Canada, the purchaser has no liability for not remitting;

- if the specific exception for “treaty-protected property” applies, there is no purchaser remittance obligation (it appears that in some circumstances if the exception does not in fact apply but the purchaser believed that it did and exercised reasonable diligence, the CRA will not pursue the purchaser for not remitting);

- if the vendor obtains and presents the purchaser with a certificate of compliance from the CRA, this relieves the purchaser from a remittance requirement (to the extent of the amount specified in the certificate); 29 When the vendor has applied for a certificate of compliance but has not yet received it by the date of the sale, a purchaser will often withhold from the purchase price and either release the funds to the vendor once the certificate of compliance has been received if this occurs by the deadline for the purchaser to remit, or continue to hold the funds if the CRA issues a “comfort letter” allowing the purchaser to delay remittance pending issuance of the certificate. or

- the purchaser can withhold and remit the required amount from the purchase price to satisfy its obligations, and leave the non-resident to seek a refund from the CRA if the amount withheld and remitted is less than the non-resident’s tax owing.

The amount of the purchaser’s remittance obligation must be received by the CRA within 30 days from the end of the month in which the property was acquired (for example, October 30 for a property acquired in September). A purchaser that fails to remit the amount (if any) required under the purchaser remittance obligation is liable to pay that amount as a tax (ss. 116(5) and (5.3)). Such a purchaser is also liable for interest on the unremitted amount and may also be assessed a penalty equal to 10% of the amount that was required to have been remitted (ss. 227(9.3) and 227(9)(a)). For second and subsequent failures to remit during the same year, or if the failure to remit was made knowingly or under circumstances amounting to gross negligence, the penalty is 20% of the amount required to be remitted (s. 227(9)(b)). There is no statutory time limit for the CRA to assess under these provisions (s. 227(10.1)).

How the parties manage the purchaser’s remittance obligation should be addressed early in the negotiation process. If the property being acquired is clearly not TCP (perhaps supported by a seller representation to this effect in the sale agreement), purchasers will typically agree not to withhold and remit. If the subject property might reasonably be TCP, arm’s-length purchasers will often take the position that they should bear no risk and advise the non-resident seller that they will withhold and remit unless the seller obtains a certificate of compliance from the CRA. In some cases the seller may convince the purchaser not to do so by agreeing to indemnify the purchaser in the event that the CRA asserts a s. 116 purchaser remittance obligation exists (i.e., the property is TCP and is not treaty-exempt). In such circumstances a purchaser may insist that the seller take all reasonable steps to minimize the purchaser’s potential liability (e.g., preparing and filing a Form T2062C to support a claim of treaty exemption). Figure 2 summarizes the purchaser’s remittance obligation.

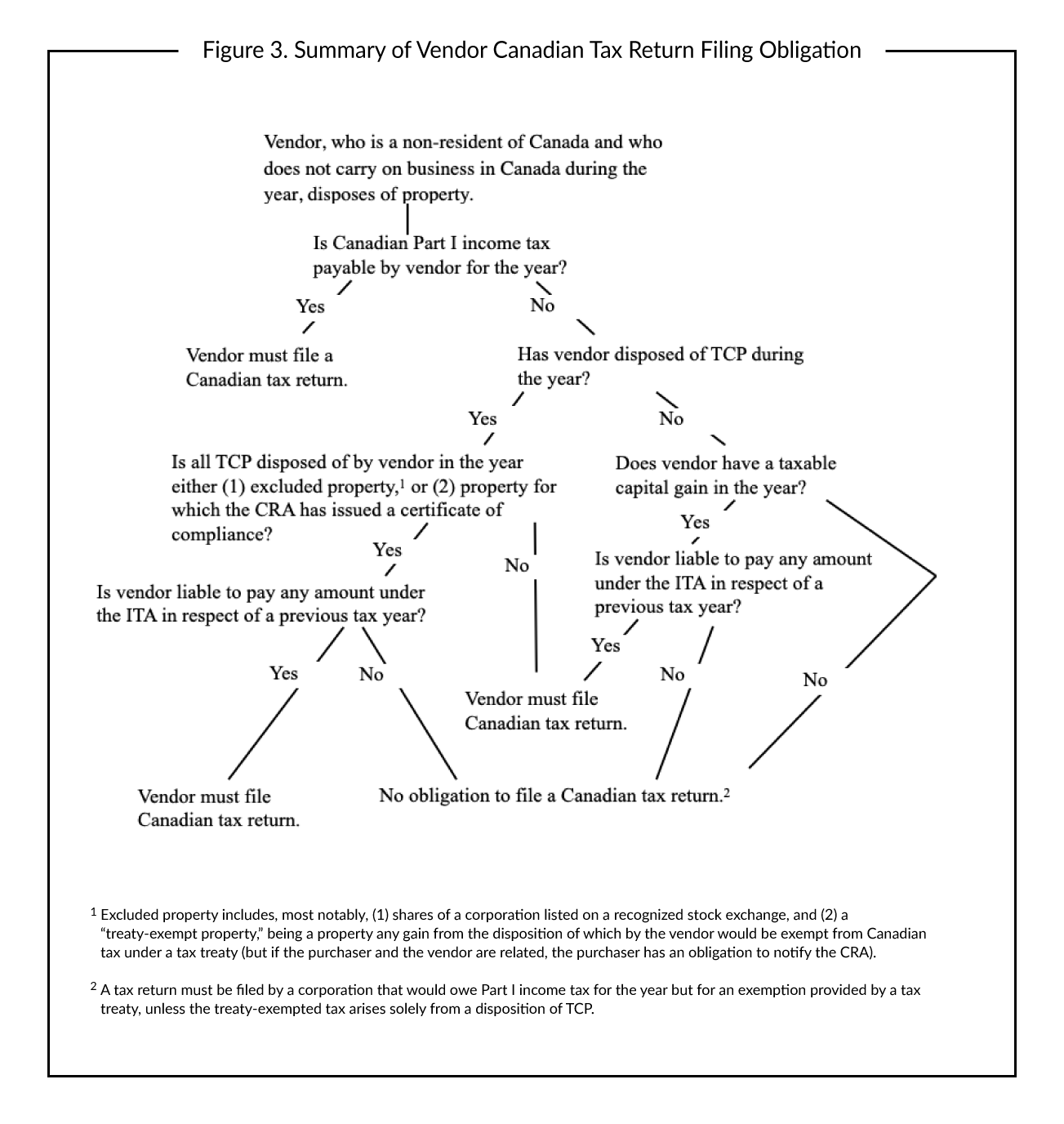

Vendor Tax Return Filing

The third element of the 116 system is the vendor’s obligation to file a Canadian tax return for the year the property is disposed of. Filing obligations for corporations are largely similar although not identical to those for natural persons and trusts. Figure 3 summarizes the tax return filing obligation of a vendor who at no time during the year carries on business in Canada or is resident in Canada. 30 Carrying on business in Canada requires a corporation to file an income tax return for the year; see s. 150(1)(a)(i)(B).

There are essentially 4 bases upon which a non-resident not carrying on business in Canada during a taxation year may be required to file a Canadian income tax return for the year:

- the non-resident owes Canadian income tax under Part I of the ITA for the year;

- the non-resident disposed of TCP during the year, unless all of the TCP disposed of by the vendor in that year was either “excluded property” or property for which the CRA has issued a certificate of compliance (see above under Vendor Notification);

- the non-resident has a taxable capital gain for the year, other than from a disposition of “excluded property” or property for which the CRA has issued a certificate of compliance (see above under Vendor Notification); or

- the non-resident is a corporation that would owe tax under Part I for the year but is exempted under a tax treaty that prevents Canada from taxing the corporation on the relevant income or gain, other than an exemption for a disposition of TCP that is “treaty-protected property” 31 Defined in s. 248(1) as “property any income or gain from the disposition of which by the taxpayer at that time would, because of a tax treaty with another country, be exempt. of the corporation.

Tax returns for corporations are due within six months from the end of the tax year, while those for trusts are due 90 days from the end of the year. Natural persons are required to file a tax return for any particular year by April 30 of the following year (self-employed persons have until to June 15 to file but must pay any amounts owing by April 30).

Failure to file an income tax return for a tax year when required exposes the person to a penalty equal to the total of (i) 5% of the person’s unpaid Part I tax that is payable for the tax year and (ii) 1% of the person’s unpaid Part I tax payable for the year for each complete month, up to 12 months, for which the return was not filed (s. 162(1)). The penalty applicable to a non-resident corporation that fails to file when required is the greater of the amount described in the preceding sentence or $100 plus $25 per day for each day the return is not filed, up to a maximum of $2,500 (s. 162(2.1)).

3. Emigration

- On the right facts, emigration of a corporation out of Canada (i.e., cessation of Canadian tax residence) can be a useful means of exiting the Canadian tax system, in particular where a sale of the Canadian corporation would have unfavourable tax consequences in the seller’s home country

- An emigrating corporation is deemed to have disposed of all of its property for fair market value proceeds of disposition, such that all gains and losses are deemed realized

- In addition, a special departure tax is levied on the emigrating corporation, based on its net surplus (fair market value of assets less its debts and the PUC of its shares). The rate of such tax is 25%, but if the corporation is emigrating to a country with a Canadian tax treaty, the rate is reduced to the most favourable dividend withholding tax rate in that treaty (often as low as 5%)

Canada’s income tax regime is a “closed” system, such that becoming a resident of Canada or ceasing to be resident in Canada are taxable events. In the case of ceasing to be resident in Canada for ITA purposes, there is generally a “settling up” of matters within the Canadian tax system.

This is accomplished by causing the following to occur (s. 128.1(4)):

- the emigrating taxpayer is deemed to have disposed of all of its property for proceeds of disposition equal to its fair market value in its final taxation year of Canadian fiscal residence, such that accrued gains and losses are realized. In the case of an emigrating taxpayer that is not a corporation (i.e., a natural person or a trust), an exception is made for certain properties that the person remains taxable in Canada on after ceasing to be a Canadian resident (e.g., land in Canada, interests in timber, mining or oil & gas properties in Canada, etc.); 32 If the taxpayer is a natural person who was resident in Canada for less than 5 years, any property owned at the time they became a Canadian resident or inherited while resident in Canada is also exempted from the deemed disposition.

- for all property deemed disposed of as above, the taxpayer is deemed to have a new cost basis equal to its fair market value, and

- if the emigrating taxpayer is a trust or corporation, it is deemed to have a taxation year-end immediately before ceasing to be resident in Canada.

Emigrants other than corporations have the option of posting security for tax arising from deemed dispositions (s. 220(4.5)).

If the emigrating taxpayer is a corporation, a second-level tax applies that is roughly comparable to what would occur if the corporation were liquidated and its net assets distributed to shareholders who are non-residents of Canada. This “departure tax” is computed as 25% of the excess (if any) of the fair market value of the corporation’s assets immediately prior to ceasing to be a Canadian resident, less the sum of its debts and obligations (other than dividends) and the PUC of its shares (s. 219.1(1)). However, the 25% rate is typically reduced under s. 219.3, which applies where the emigrating corporation has become fiscally resident in a country with which Canada has a tax treaty. In such circumstances, the applicable rate of departure tax is reduced from 25% down to the dividend withholding tax rate in that treaty applicable to a dividend paid by a Canadian corporation to a corporation resident in the other treaty country that owns all of the shares of the Canadian dividend payer, viz., the most favourable rate of dividend withholding tax provided for in that treaty (other than for tax-exempts). In most cases this will be between 5% and 15%. Thus, an emigrating corporation can significantly reduce its departure tax by emigrating to a tax treaty jurisdiction.

Where the FAD rules have previously applied to the emigrating corporation to reduce the PUC of its shares, in certain circumstances the PUC of those shares can be reinstated for purposes of computing its s. 219.1 departure tax (s. 219.1(3)-(4)). Conversely, the emigrating corporation’s PUC may be deemed to be nil for this purpose where the result of the emigration is that the emigrating corporation will become a foreign affiliate of another Canadian corporation that is controlled by a non-resident person or group of non-residents not dealing at arm’s-length with one another (s. 219.1(2)).